Here's my monthly wrap-up of global financial markets for Australian investors -

- Share markets are down – but how serious is it?

- Currency markets – big moves are afoot. Can Trump talk down the dollar?

- Where is the ‘safe haven’ money going – if not into bonds or US dollars?

- Progress on inflation, interest rates, recession fears, and plenty more.

Greetings fellow investors! - Here’s my monthly snapshot on global markets for Aussie investors.

The orange elephant in the room is still Trump, and I will not even attempt to summarise or make sense of what he did or said during the month. By the time I finish typing any sentence it will probably be out of date anyway. For investors, all that really matters is what American consumers, companies, and investors make of it, because that is what drives world markets.

The overall theme for the month was that American consumers are becoming increasingly nervous about spending, and American companies are becoming increasingly nervous about investing, when nobody knows what the rules will be tomorrow, let alone next year. All of this is making investors nervous about the prospects for company revenues and profits in the short and medium terms, and they continued to rotate out of shares.

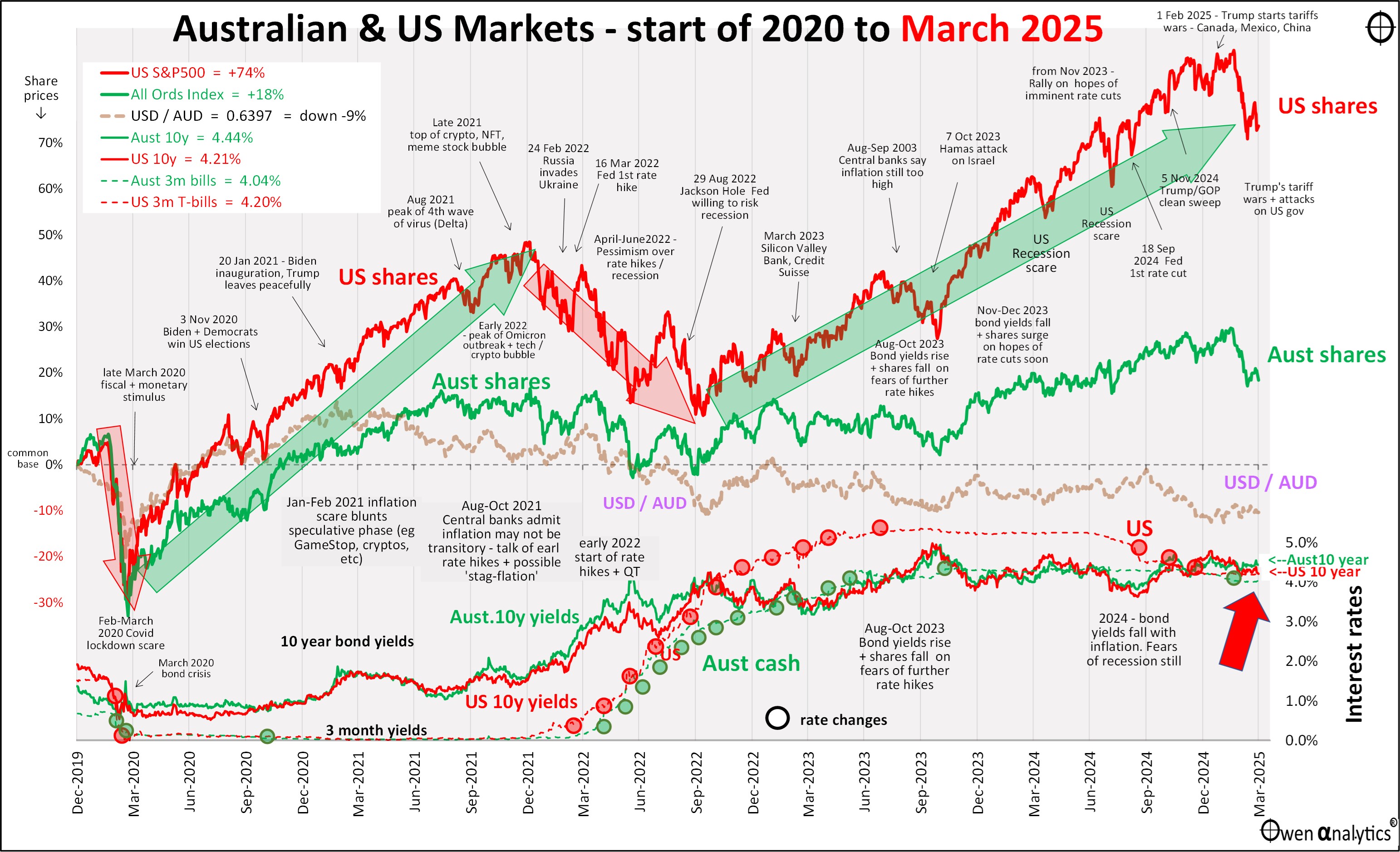

But first - my essential 1-page snapshot chart - covering Australian and US share markets, short and long-term interest rates, inflation, and the AUD/USD exchange rate. As usual, there are two versions – first is the traditional version on a single chart:

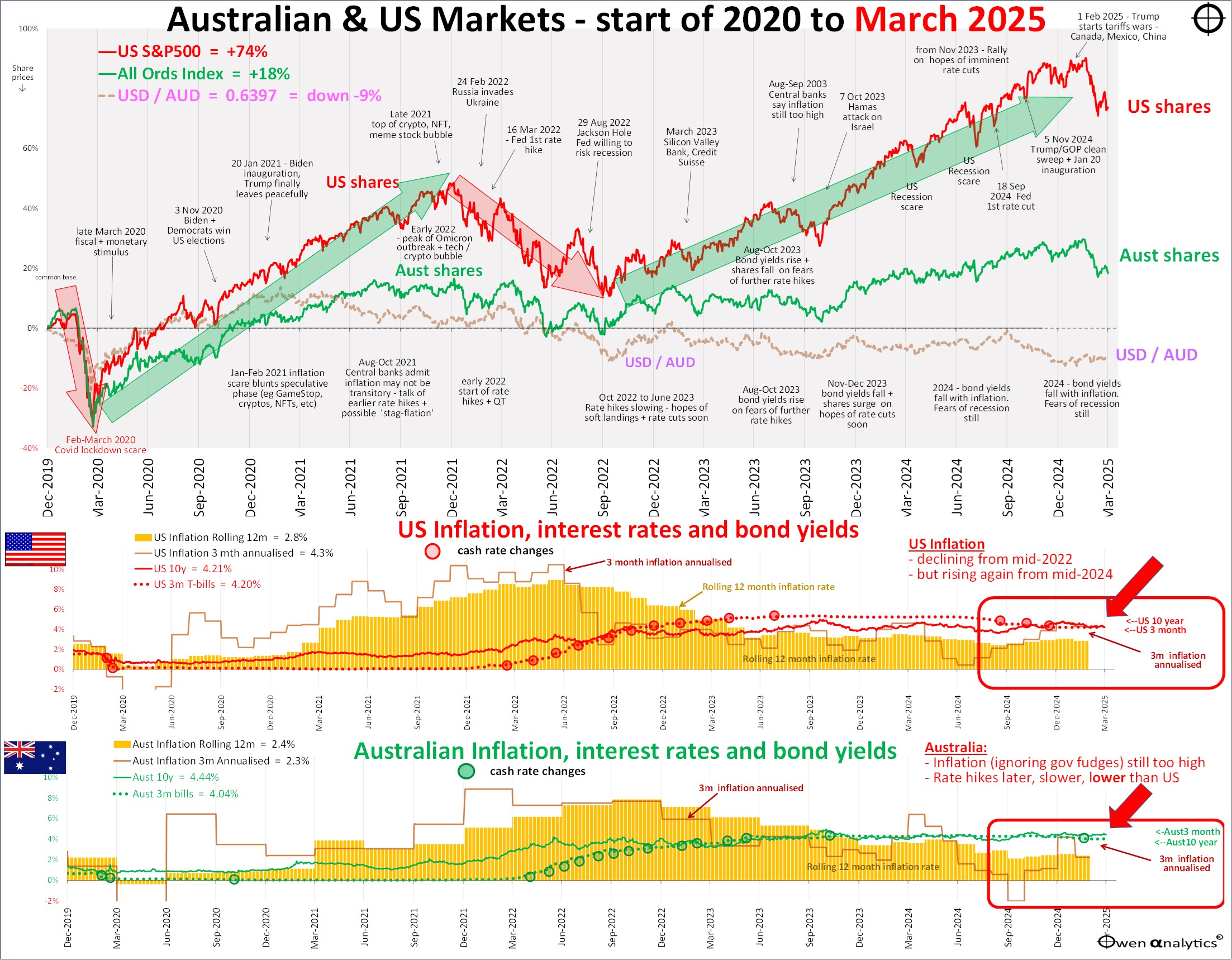

Also the alternate version below, requested and used by several advisers - showing Australian and US inflation separately in the lower sections (I deal with inflation in greater detail below):

Shares – minor hiccup? or start of the BIG one?

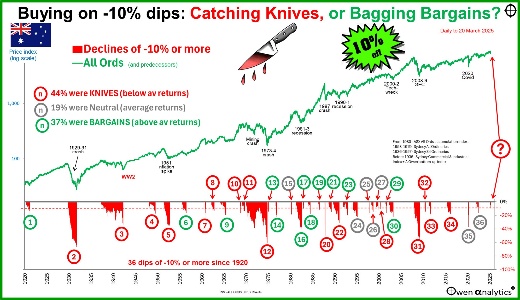

There has been a lot of media coverage over the so-called ‘correction’ or ‘bear market’ on share markets, after the US and some other markets (but not the ASX, just) dipped -10% during the month. The fact is that 10% falls are actually very common.

To put the recent dips in context, on the above charts of US and Australian markets over the past five years, each market has seen a lot worse in two much deeper dips:

- The US market (S&P500 – red line) fell -34% in the Feb-March 2020 Covid lockdown sell-off, and then fell -25% in the Jan-October 2022 sell-off triggered by aggressive rate hikes to tackle inflation.

- The Australian market (All Ords index – green line) fell -37% in the 2020 Covid lockdown sell-off, and then fell -17% in the 2022 rate hike sell-off.

The 2020 and 2022 sell-offs were each much deeper than the 2025 mini-sell-off. That does not mean that the current sell-off is over. But it does show how common sell-offs of a lot more than -10% are.

The second comment I would make is that share markets very quickly recovered both the 2020 and 2022 sell-offs. Again, I am not predicting that the market will rebound as quickly this time, but it does demonstrate that a -10% sell-off is not the end of the world as we know it!

For my recent stories on my study of the dozens of times the US and Australian share markets have dropped by -10% or more in the past – see:

Industry Sectors

All global industry sectors were down in March except for fossil fuel burners (Energy, Utilities, with oil prices back above $70/barrel), and Materials (lifted by gold miners with the surging gold price). Everything else was down, pretty much across the board.

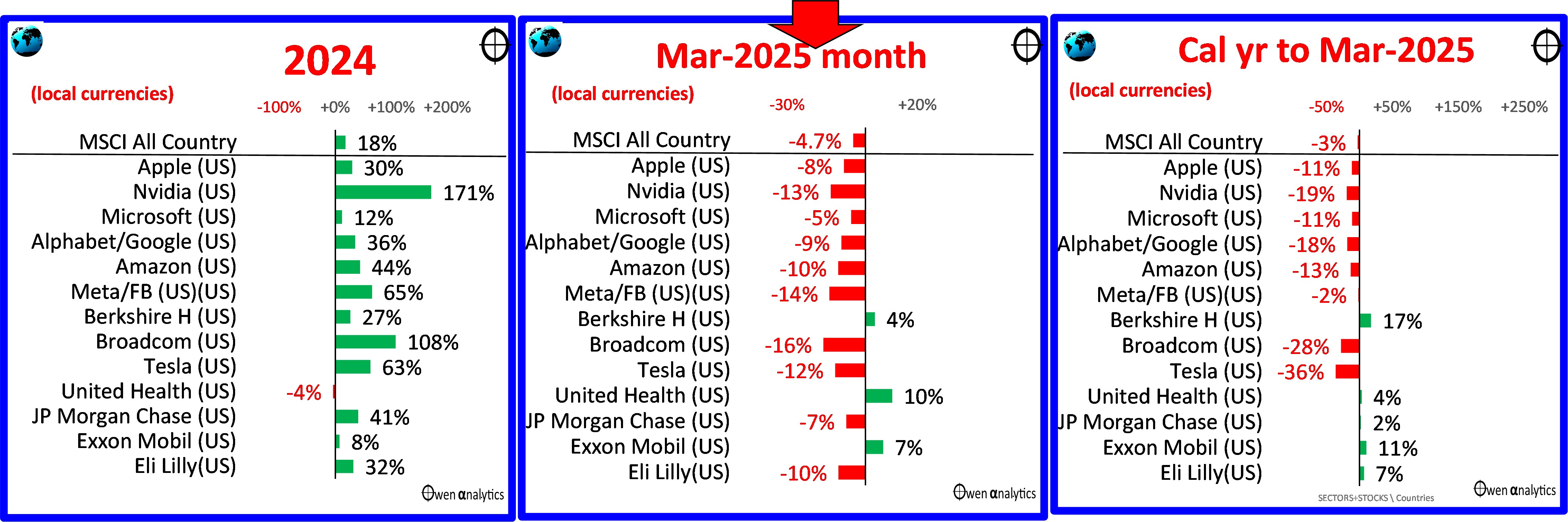

Major stocks

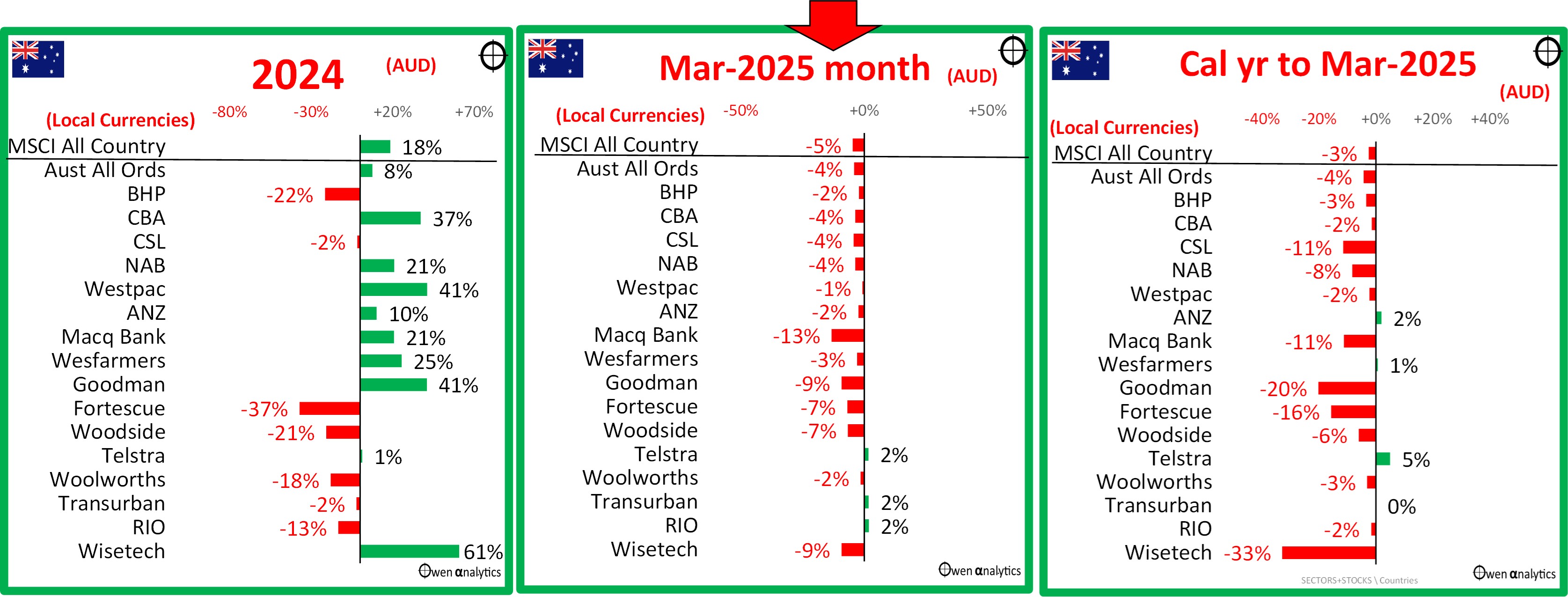

Here is the picture for the major global stocks (all of which are US based) – again showing 2024 (left), latest month (middle), and 2025 calendar year to date (right):

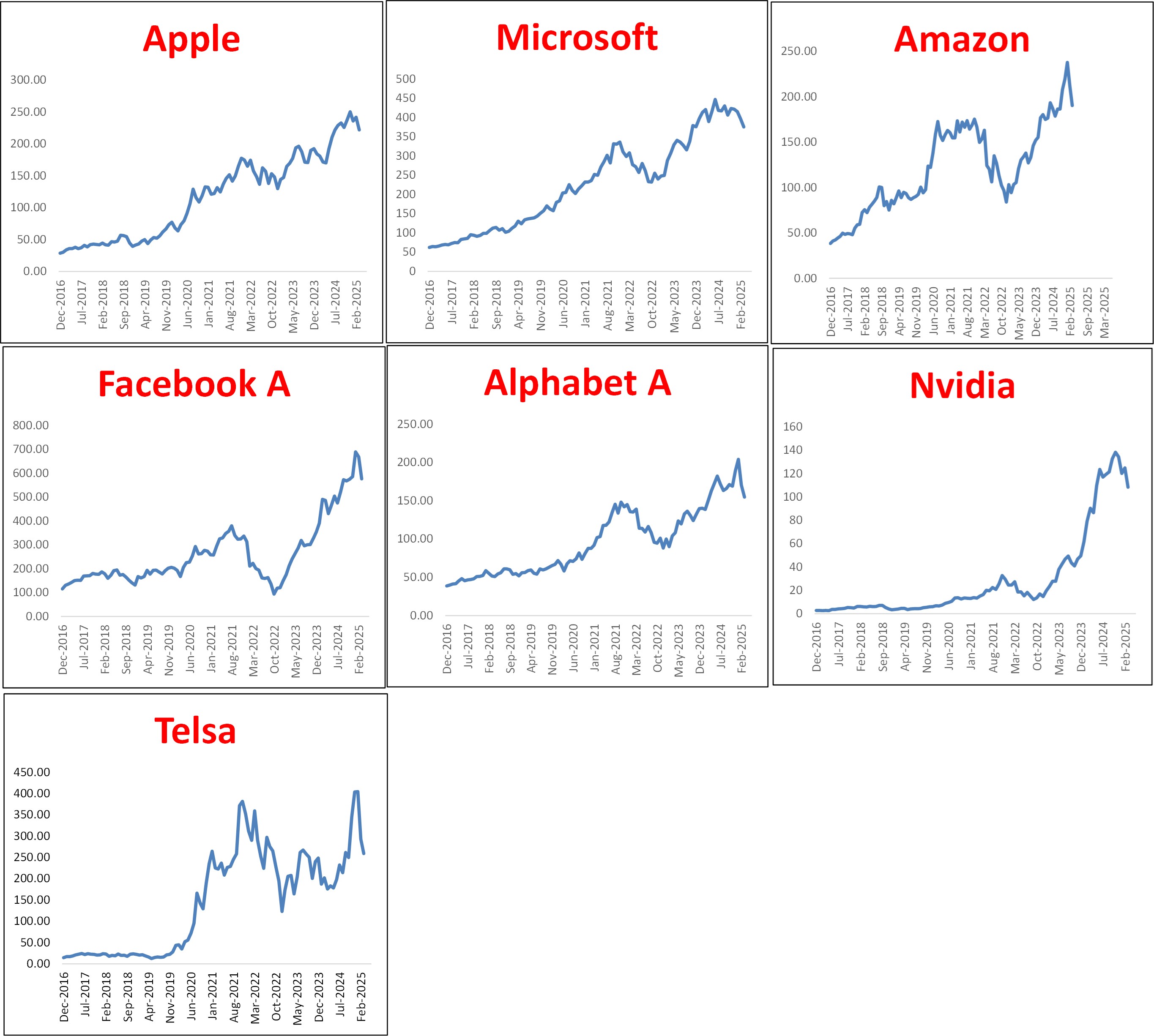

Here are the so-called ‘Magnificent Seven’ stocks over the past decade -

All of their share prices are down so far this year, but all are still up hundreds of percent over the past few years. They are also still very expensive on a range of metrics. See my recent report on how they stack up on revenues, profits, dividends, and pricing -

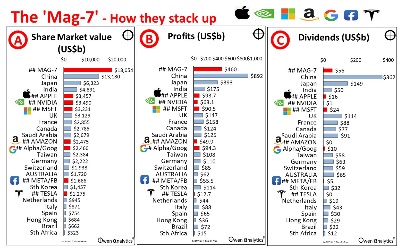

Major country share markets

The US market (which makes up 65% of overall global share market value) dragged down the global index in March (middle chart below), but all other major markets were also lower almost across the board.

The only exception was China, led by Baidu and Tencent. There are two main reasons for the recent min-revival in Chinese stocks – the first is Xi Jinping welcoming previously exiled tech oligarchs back into the fold. Xi has suddenly realised he needs them for China to dominate world markets in new high-tech industries like ai, surveillance tech, EVs, solar panels, wind turbines, etc. The second factor is the recently announced plan to re-capitalise six of China’s state-controlled banks, to allow them to boost lending in an effort to stimulate China’s stalled economy.

On a 2025 year-to-date basis (right chart above), Europe, UK, and China are still ahead, despite heavy falls from tariff-affected exporting giants like LVMH, Kering (France), Diageo (UK), SAP, Adidas (Germany).

Australian shares

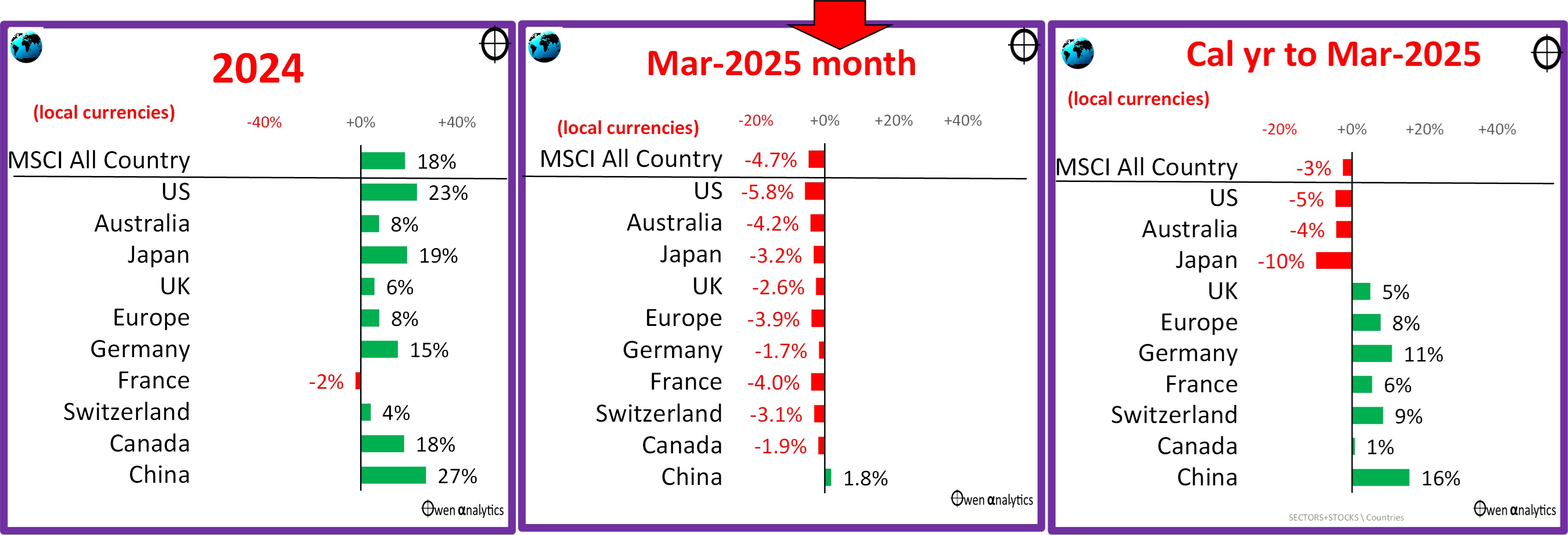

The local share market was also dragged down in the global retreat in March, as prices fell almost across the board (middle chart below) -

Year to date, it is now also a sea of red ink. For the big banks, it looks like some sanity is emerging about their levels of fundamental over-pricing. Banks had very strong years in 2023 and 2024 (in share price gains, not in profits or dividends), and they are still over-priced on a range of different measures, given their stagnant growth and seemingly endless self-inflicted problems.

The other main sector of the local market – miners - are mostly down this year with the continued slide in commodities prices – mainly iron ore, industrial metals, and battery metals. Mineral Resources has had added problems with founder Chris Elison’s shenanigans.

Gold miners were the only bright spot with the continued surge in the gold price (see below). Wisetech has been the big loser this year (but was the biggest gainer last year) as founder Richard White battles his board who are trying to remove him. Professional directors want compliant, obedient CEOs, but investors what founders who build businesses and make money for them. It is a fascinating battle.

Inflation & interest rates

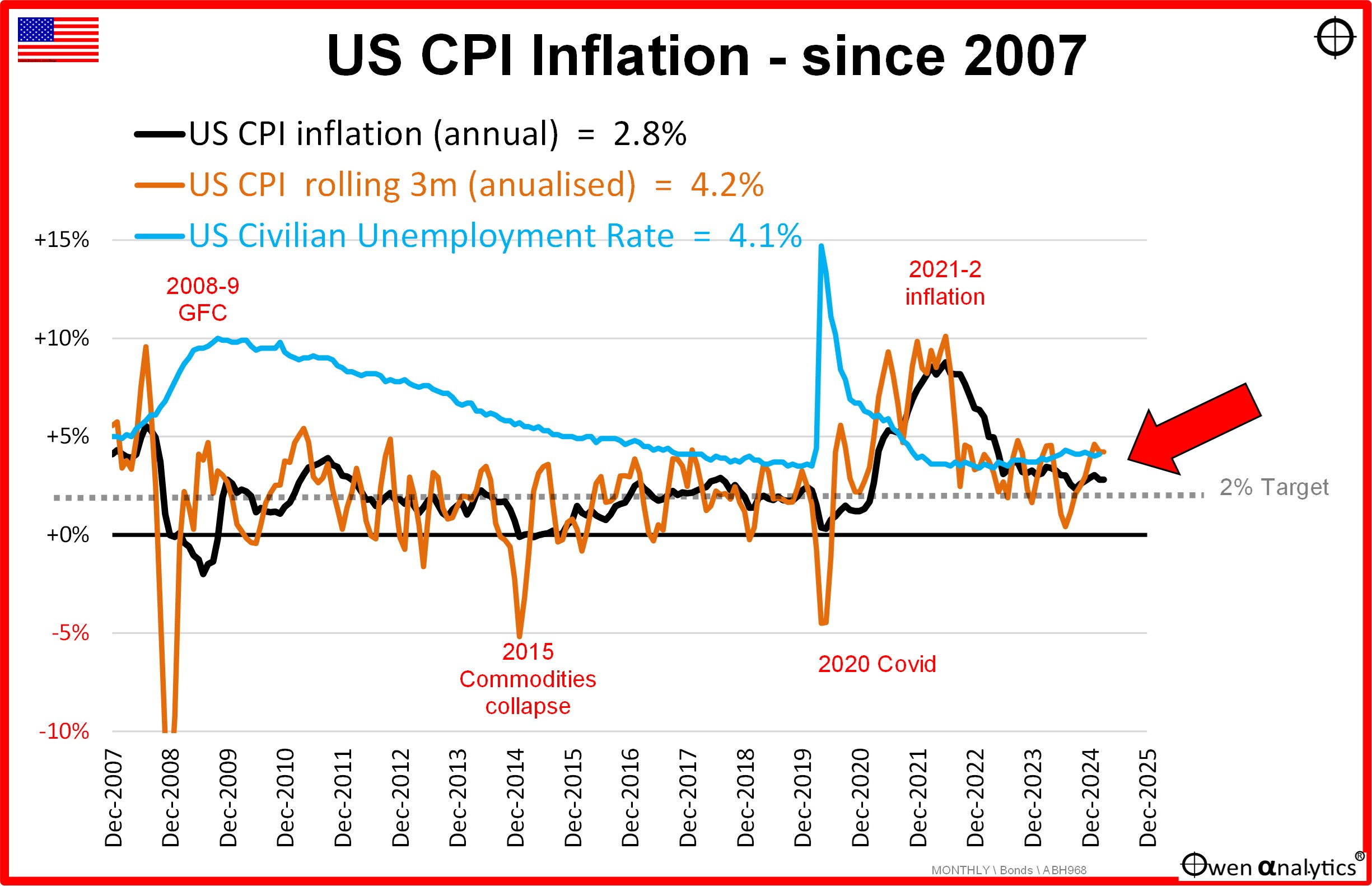

First, to the US market - After three rate cuts in September, November and December 2024, the Fed hit the pause button and said they are in no hurry to cut rates further. The problem is that US inflation is on the rise again – the 12-month rate at 2.8%, and annualised 3-month running rate rising to 4.3%. The Fed’s preferred measure, Personal Consumption Expenditure (PCE) is also above target still at 2.8%.

On top of that, the jobs market remains strong, with unemployment rising from 4.0% to 4.1% but still relatively low. Here is the US picture:

Probably the strangest moment of the month was Fed chair Jay Powell’s comment that signs of tariff-induced inflation in the US may be ‘transitory’. This is probably an indication of the extreme pressure he is under – not unlike the situation with the RBA here (see below).

One would have thought after his unfortunate ‘transitory’ comments in 2021, that he would have banished the word to the dustbin of history, and also banished it from his personal vocabulary. (In 2021 he was caught napping when he dismissed rising US inflation as ‘transitory’. It wasn’t, but he let it shoot up to 8.8% before belatedly admitting his error and switching to attack mode with rate hikes in 2022.)

The world waits with bated breath to see just how ‘transitory’ the Trump tariff inflation turns out to be.

Australia

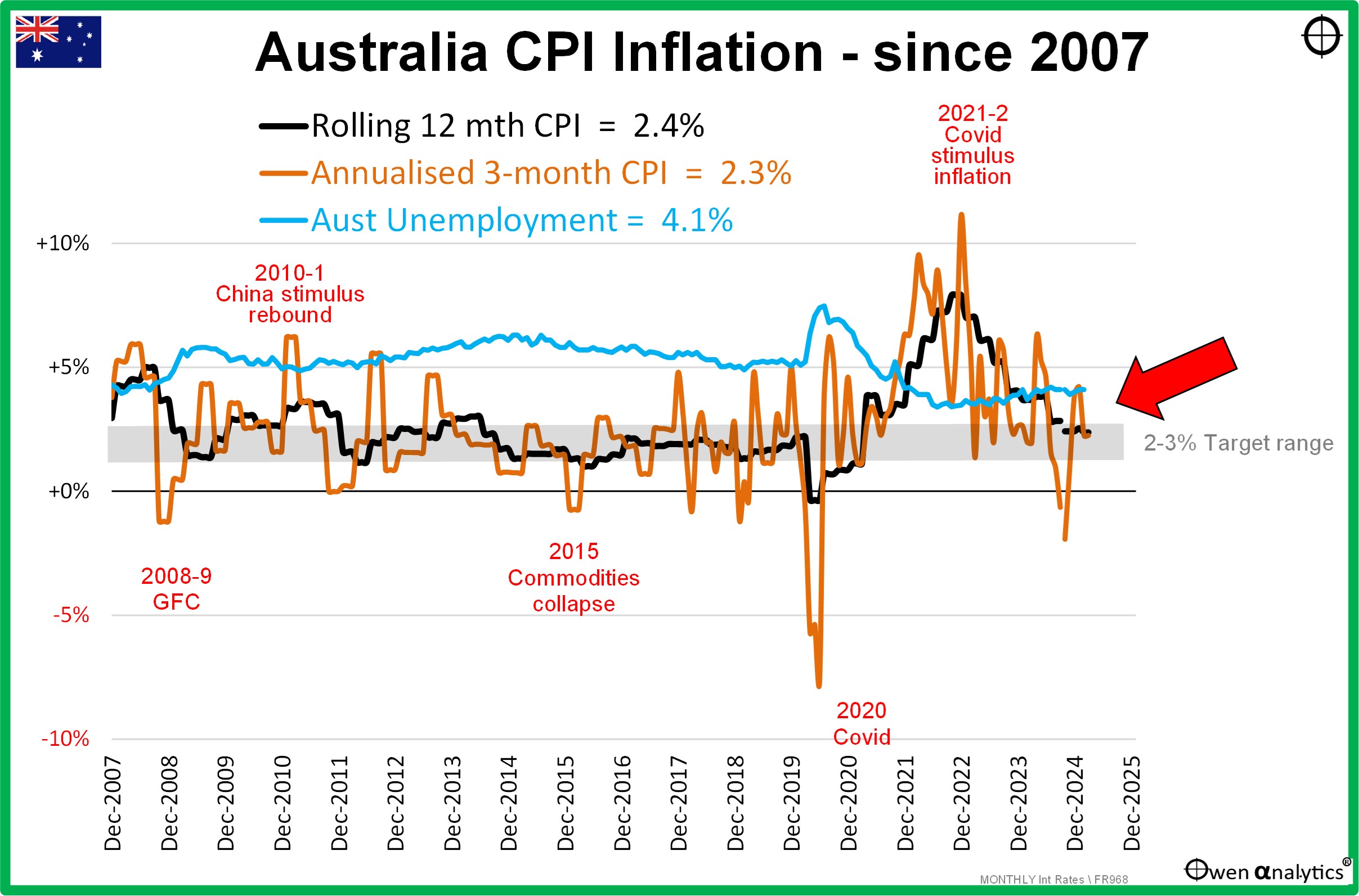

The RBA made its first reluctant and belated rate cut on 18 February – down by 0.25% to 4.1%. The RBA rate hikes were later, slower, and lower than the rest of the world in attacking inflation, plus we have a more centralised wages system here and a pro-wage inflation government with expansionary spending, so inflation has remained stickier here than elsewhere.

There is no doubt the RBA has lost some of its ‘independence’ under smiling Jim Charmer’s ‘reforms’, and there also is a lively debate about the extent of political pressure on the RBA chief to change her wording after the June 2024 RBA meeting on the revised causes of the sticky inflation problem. Her awkward back-tracking on the statement, and the reasons accompanying the eventual February rate cut were far from compelling.

Here is the Australian picture:

12-month CPI inflation is running at 2.4%, and the annualised 3-month rate is 2.3%, and the RBA’s preferred ‘trimmed mean’ measure is down from 2.8% to 2.7%. However, these numbers are still being artificially depressed by temporary government power and rent subsidies.

As in the case of the US, the most obvious reason for rate cuts would be a local recession, which would lift unemployment and probably soften inflation pressures, allowing (or necessitating) rate cuts.

Unemployment remains a very tight 4.1%, with record ‘participation rates’ (the number of people in the workforce as a percentage of working age population), but that is almost entirely due to expansionary government hiring.

Meanwhile, in the real world, business insolvencies have shot up to levels not seen since the 1990-1 recession. Look out for my upcoming story on this. Job numbers are booming in the government sector, but business is doing it tough.

In summary - the government is artificially suppressing both the inflation numbers (with subsidies and hand-outs), and also the unemployment numbers (with deficit-funded jobs in the ever-expanding government sector).

A reader asked me the other day whether the ABS should report private GDP and public GDP numbers separately so we can see the government economy versus the real economy. My answer was that the government probably already thinks that the government IS the economy. It is getting to look that way.

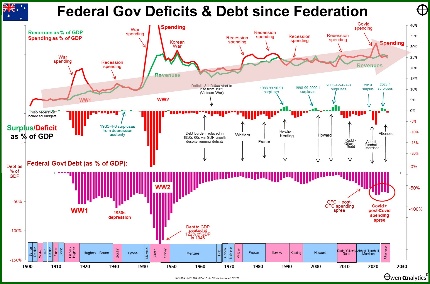

Check out my recent story on the history of Federal government deficits and debts in Australia –

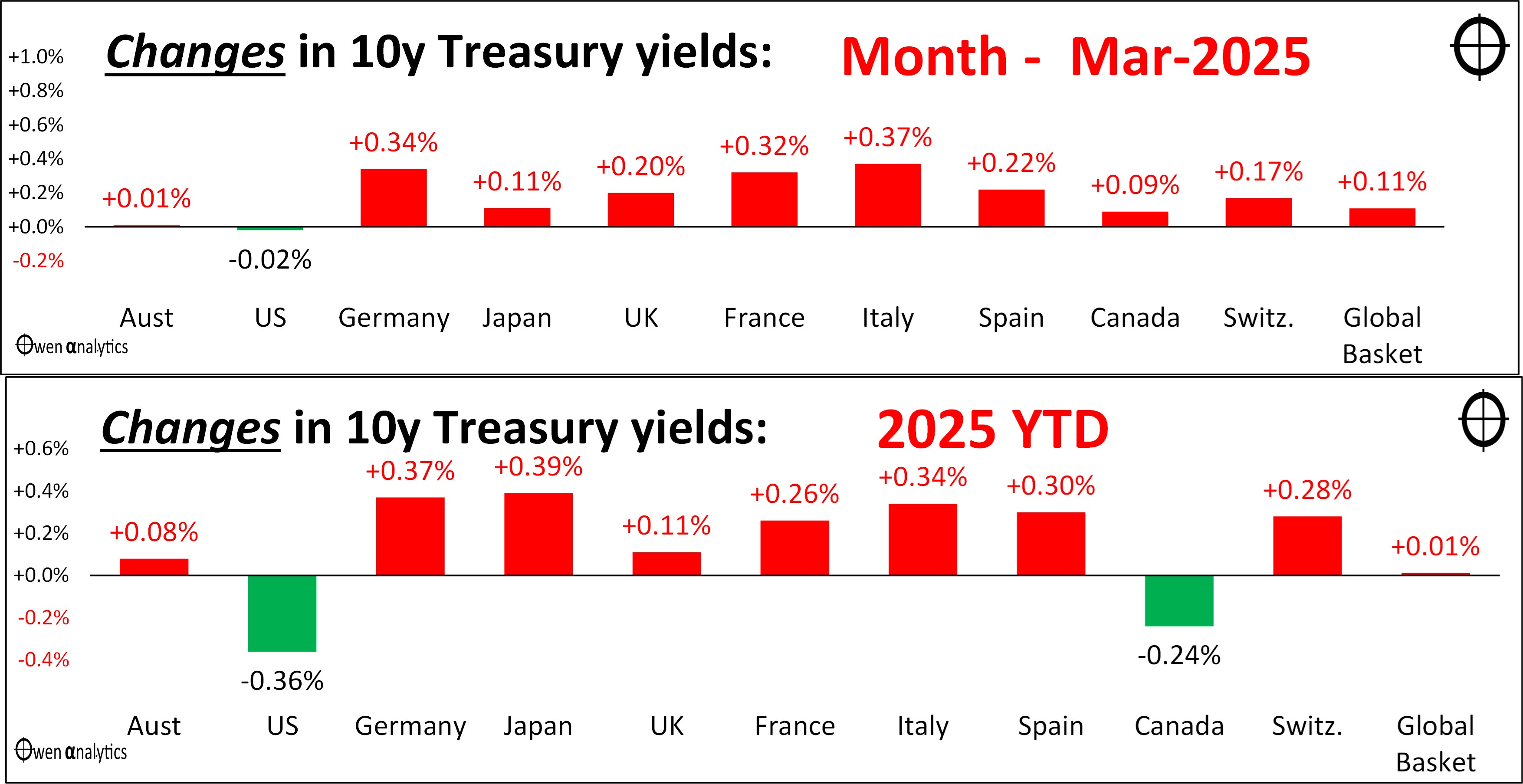

Bond yields

Bond yields rose around the world in March (upper chart below) on rising inflation fears (tariff impacts plus rising defence spending), with the exception of the US where yields fell – as recession fears appear to be outweighing inflation fears.

For 2025 year-to-date (lower chart) yields are higher everywhere except US and its major trading/trade war partner Canada.

Yield rises are in red (as they cause capital losses), and yield declines are green (capital gains on bonds).

Bonds in portfolios?

(Most Aussie direct investors don’t get bonds, but I study them and comment on them regularly because professional and institutional diversified funds (like the big Super funds) are required by their mandate rules to have sizeable allocations to bonds. Personally, I am not governed by mandates, but I do have to use them in my roles on Investment Committees, and they do have legitimate roles in long-term portfolios.)

Government bonds often do well in economic slowdowns that are usually (but not always) accompanied by falling bond yields as inflation falls – a prime example was the 2008-9 GFC. But the gains on bonds on the way into recessions are quickly lost again on the way out.

You need to be extremely good to time getting in and out of bonds on the way into, and out, of recessions! I have done it successfully when I was younger and more nimble, but I am happy to sit out the bond market in the current conditions of problematic medium term inflation.

Bond markets have had a terrible time since 2021 with the return of inflation, including the worst losses on bond markets in a century in 2022. I have been out of fixed rate bonds in portfolios since 2020 (preferring high grade floating rate instead). I remain bearish on fixed rate this year as well, with inflation remaining sticky in Australia and the US.

Currency actions – something big is afoot

There are interesting things happening in currency markets. The US dollar fell against all other major currencies in March, which is very unusual when share prices fall heavily. The almost universal rule is that whenever there is a broad share market sell-off, the US dollar always rises as a safe haven. Even when the cause of the problem is the US itself (like the 2008-9 GFC, the 2011 credit downgrade / debt ceiling crisis, and many others), the US dollar will always rise as a safe haven in a broad sell-off.

The strong dollar real is a problem for Trump, who wants a lower dollar to help US exporters. A rising dollar neutralises the impact of the tariffs. For example, a 10% US tariff on imports makes imports more expensive and domestic producers more competitive. But if the US dollar rises by 10%, it brings down the cost of imports by 10%, and neutralises the effect of the tariff.

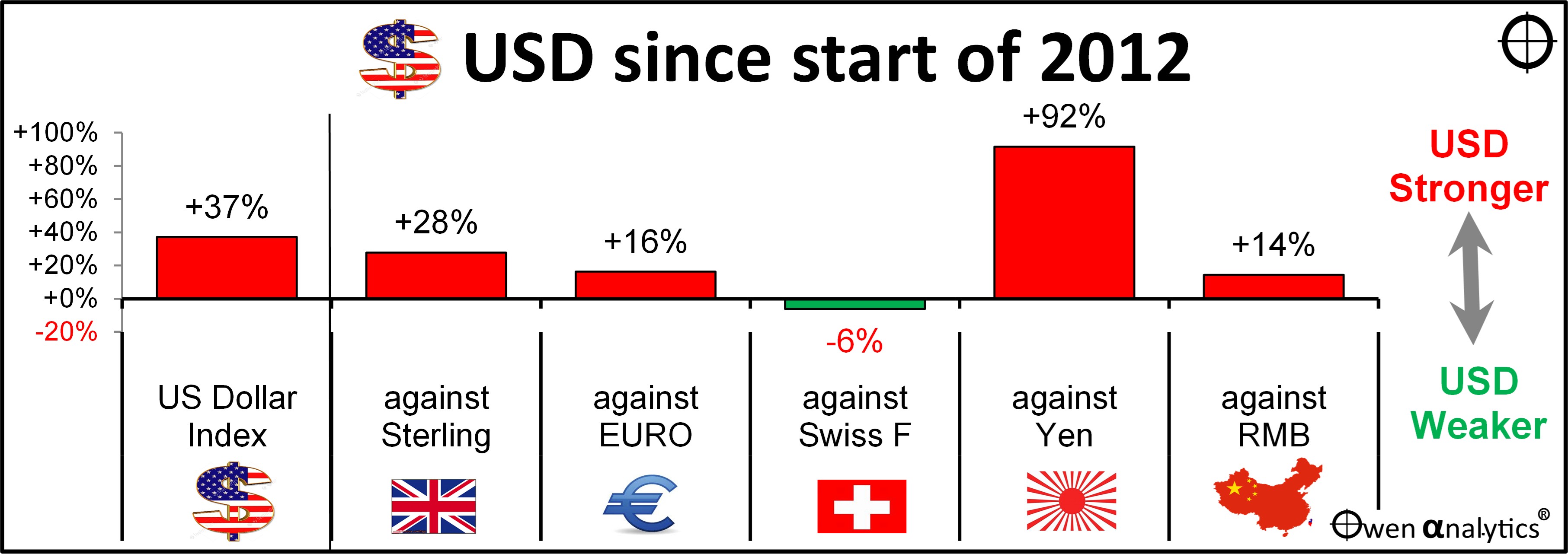

Contrary to popular media naratives, the US dollar is not on its last legs. In fact it is the reverse. The US dollar has been rising pretty much in a straight line since the August 2011 US credit rating downgrade. Since the start of 2012 it has gained 37% against its major trading partners:

This has made US exports less competitive and it has caused the loss of millions of US jobs. For example, the cost of imported Japanese cars has halved simply because the US dollar has doubled against the Yen. If Trump slapped a 100% tariff on Japanese car imports, it would just take the relative position back to where it was in 2012.

Trump has been trying all sorts of things to try to talk down the dollar, including mentioning the possibility of defaulting on debt, and/or converting foreign-owned US bonds into perpetual or 100-year ‘century bonds' and unilaterally slashing the coupon interest. That sort of thing would amount to a Greek-style default/restructure – and that would certainly send people fleeing from the dollar.

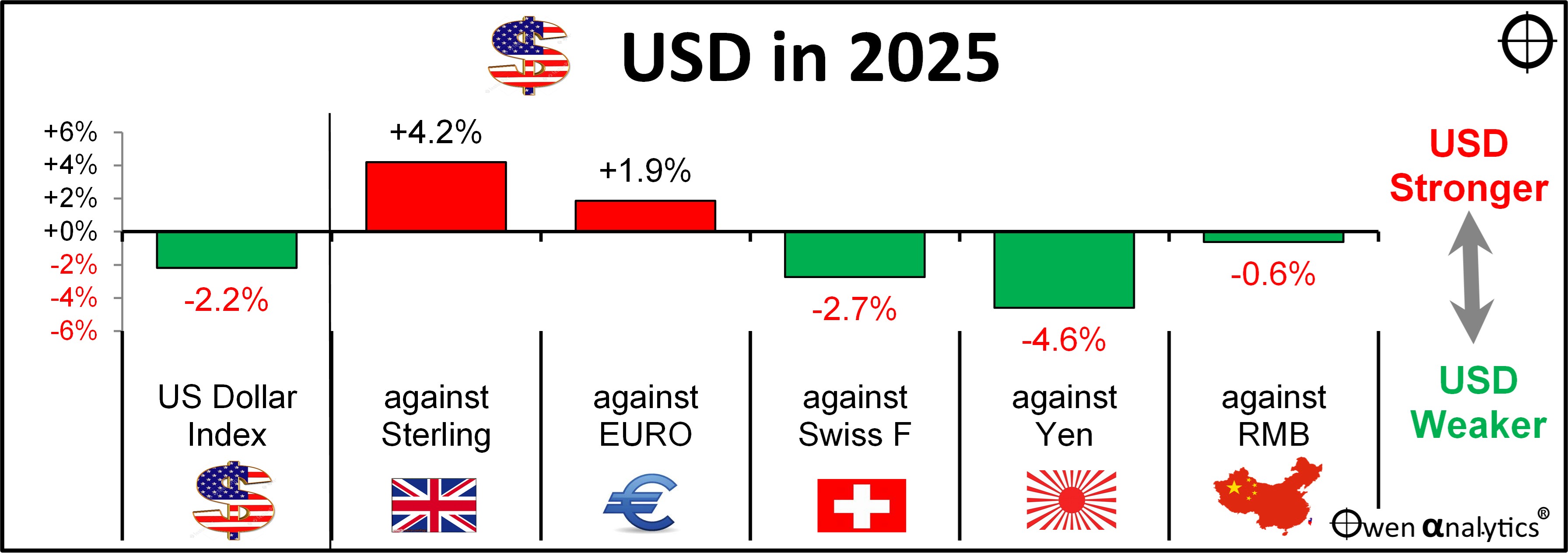

The scary talk seems to be working, and so far in 2025 he has talked down the dollar by a couple of percent, despite the fall in US and global share markets:

So he has effectively already assisted US exporters by 2%. A devaluation is much more sensible and less damaging than a tariff war. There is talk about a potential ‘Mar-a-Largo agreement’ along similar lines to the Plaza Accord in September 1985 in which the other major countries agree to sell dollars to bring down the US dollar.

Where is the money going?

If investors dumping shares have not been buying the usual safe havens - bonds or US cash, where is the money going?

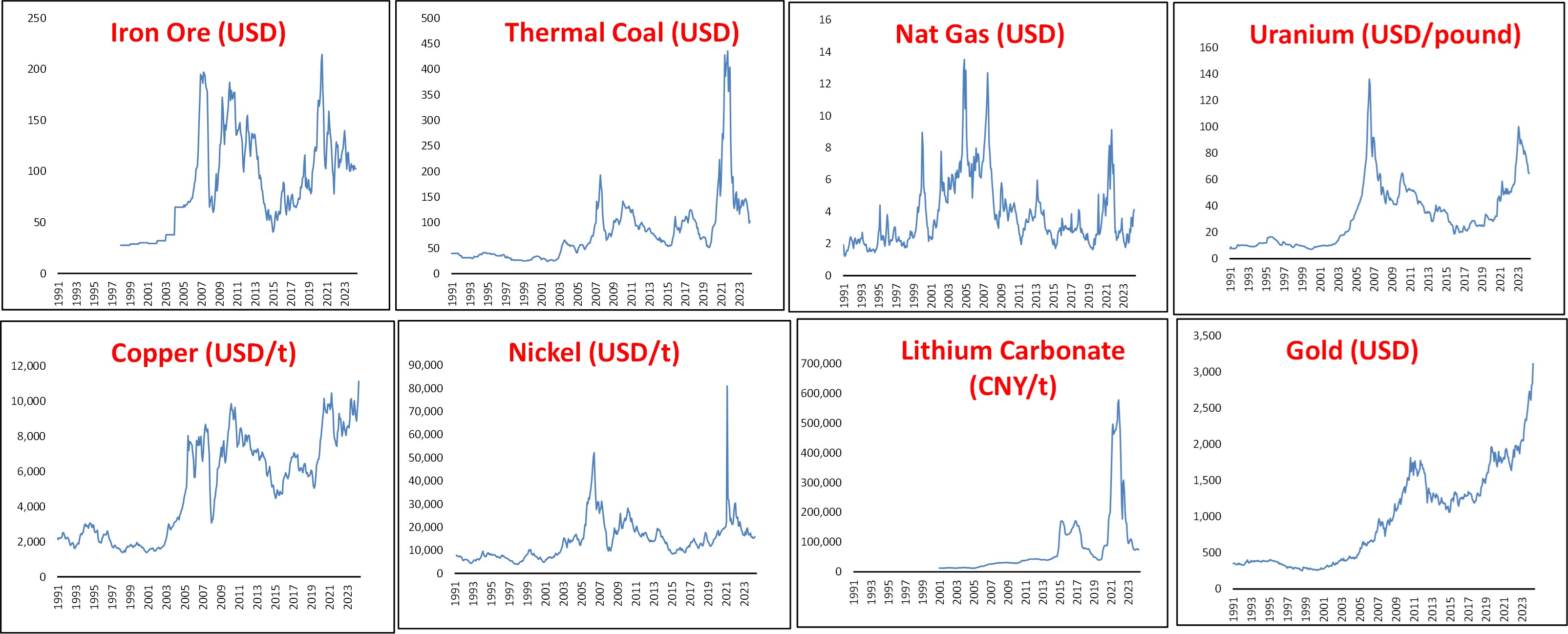

Out of these commodities price charts - which is the odd one out?

(Not it’s not Bitcoin – that is down -12% this year, and down -22% from its peak the day of Trump’s inauguration). Everything else is tanking, apart from copper, which is spiking up this year, mainly caused by a frenzy of buying in advance of Trump’s tariffs.

Gold

In US dollar terms, gold is up +19% so far in 2025, up +51% since the start of 2024, and up +64% in Australian dollar terms, because the AUD has fallen.

The main factors have been strong buying from central banks (terrified by the thought of US seizure of US dollar assets, as US did to Russia after its invasion of Ukraine). Also, Chinese nationals have been strong buyers of gold (after the collapse of the Chinese property market).

I have been studying gold (and buying judiciously in various forms) over the past 25 years since the 1980 gold frenzy (no, I was not a buyer in the 1980s gold frenzy, nor the 2011 gold frenzy – never buy anything in a buying frenzy!)

I put gold into diversified portfolios last year. In portfolios I have the un-hedged ETF version, so we get the AUD returns that benefit from the falling AUD.

But that does not mean readers should rush out and buy it now! Every year we face a whole new set of challenges.

‘Till next time – safe investing!