Ever wondered where our big dinosaur banks came from, and how they got so big? And why are they all virtually the same?

Retail banking in Australia is dominated by a cosy, government-protected oligopoly cartel – the ‘big-4’. Their products, prices (interest rates and fees), and levels of service (I use that term very loosely) are indistinguishable from one another. The main difference is their logos. Apart from that they are all as bad as each other.

It was not always this way. There were once dozens of independent banks competing for business and listed on local stock exchanges all over Australia. (Many were also listed on the London Stock Exchange, as London was the main source of British and Scottish money that financed Australia’s growth, and also its speculative bubbles).

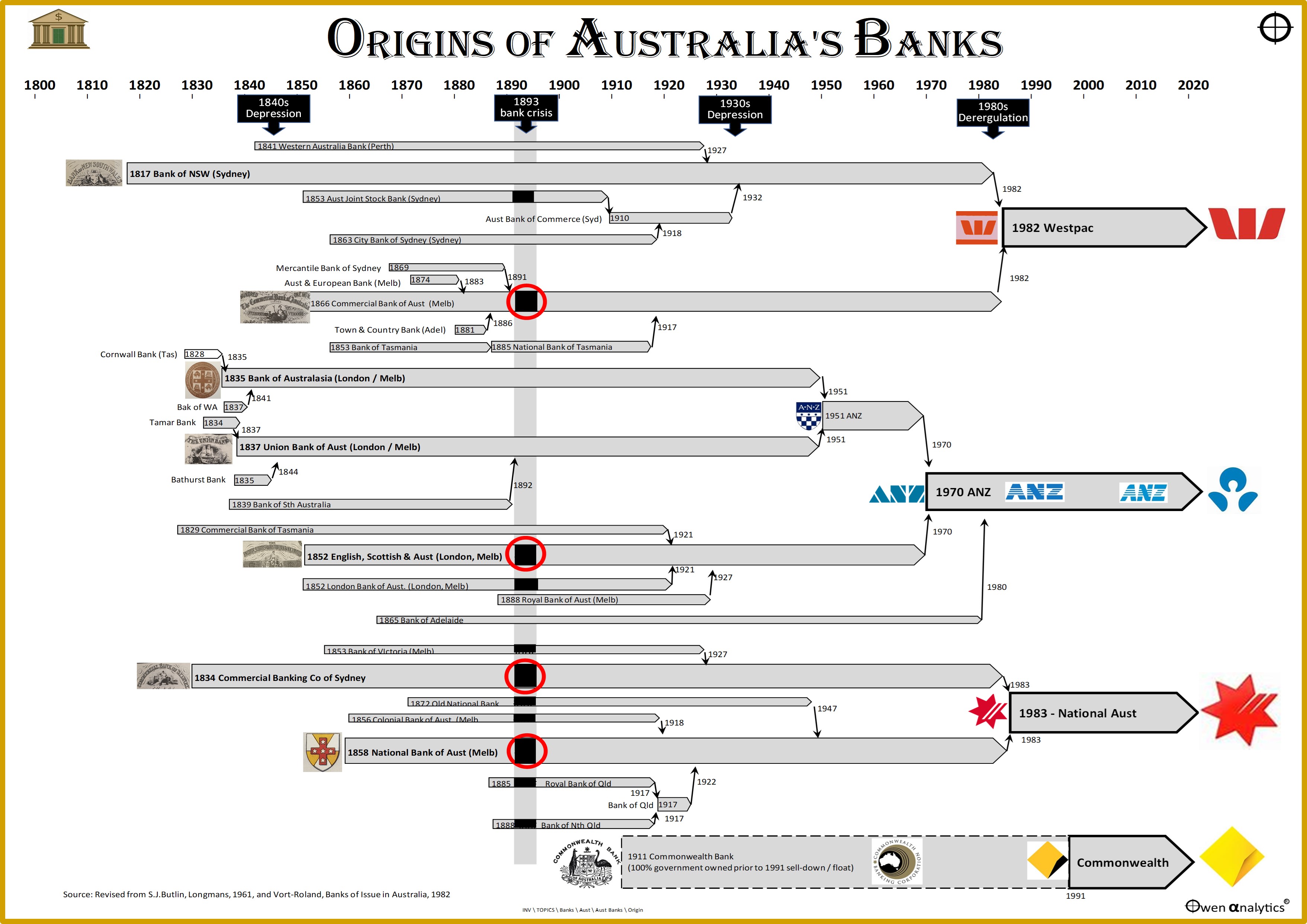

Here is how the dozens of relatively small, competitive, independent banks in Australia became the ‘big-4’:

Four pivotal events

There were four pivotal events that shaped the history of banking in Australia. (These were all global phenomena, but their effects were certainly felt here in Australia to varying degrees). These are indicated by four black arrows below the timeline running across the top of the diagram.

The four pivotal events were:

-

-

- 1840s depression – local bank failures.

-

- 1890s depression and bank crisis – this was the ‘big one’ for Aussie banks – more details below.

-

- 1930s depression – very little damage to our banks, unlike the US disaster. However, the conduct of the banks here during the 1930s depression shaped the future political and regulatory landscape for banks in Australia.

-

- 1980s deregulation – banks gobbled up everything in sight, went mad on wild lending binges, but survived.

Let’s go back to the start:

The ‘Wales’

For the first 30 years of its life under British rule, Sydney grew from a tiny, struggling British prison colony into a bustling economy without any banks at all, and with dozens of different types of currencies in circulation.

Then in 1817 Governor Lachlan Macquarie, defying direct orders from his masters in London not to do so, allowed a group of Sydney businessmen to set up Australia’s first bank – and its first company – the Bank of New South Wales.

From a standing start with one bank with a single branch in 1817, the colonies of ‘Australia’ grew to become the richest nation in the world per capita by the late 1800s – thanks to extraordinary export booms in wool, gold, silver, and base metals.

All achieved without a central bank, without a national currency, and without any regulation of banks.

During Australia’s great nation-building phase, the banks created and issued currency, controlled the supply of money and credit, set interest rates, set exchange rates, and determined the structure of their assets, liabilities, and leverage.

The federal government took away all of these powers and functions of the banks (mostly in the Second World War), and the banks never got them back. (The banks did not always handle themselves well in the pre-regulation era, and they sowed the seeds of their own demise - see Labor’s attempt to nationalise all banks in Australia! 21-7-2024).

Most over-banked nation on earth

Not only did Australia become the richest nation on earth, it also became the most over-banked nation, in terms of the number of bank branches and bank staff per capita. Part of this growth of bank branches was due to the enormous increase in wealth, economic activity, and population that accompanied the booms in agriculture and mining.

Another major factor was the relative sparseness of population and economic activities spread over vast distances.

In stark contrast - Australia’s banking market today is dominated by just four giant banks. Three of these – Westpac, ANZ, and National - were formed out of the mergers of 54 banks from the 19th century. The fourth – the Commonwealth Bank - was set up in 1911 as the federal government’s wholly-owned bank, but it was sold off to the public and listed on the ASX from 1991, and it mopped up most of the remnants of the State government banks along the way.

Westpac is essentially the original Bank of New South Wales, after merging with the Melbourne-based Commercial Bank of Australia, plus some smaller banks along the way, like the Joint Stock Bank, and City Bank of Sydney.

ANZ is essentially the merger of the three main Melbourne-based ‘London’ (or ‘Anglo’) banks, plus some smaller ones like the London Chartered Bank of Australia.

NAB is essentially the merger of the locally-funded National Bank and the Commercial Banking Company of Sydney, plus others including the Bank of Victoria and Qld National Bank.

These three mega-mergers were all carried out to ‘get big’ in readiness for the 1980s banking deregulation and entry of foreign banks into the local market. The foreign banks that did open here are long gone (a couple of tiny remnants remain), leaving the local big-4 oligopoly to dominate the local market.

But first - what is a ‘bank’?

For most of the history of banking in Australia there was no formal regulation or licencing of ‘banks’, so we need to define what we mean by a ‘bank’.

Being a ‘bank’ involves more than just deposit-taking, lending, and payments. There are many types of businesses that take deposits from the public and make loans – including building societies, credit unions, and finance companies. There are also many businesses that provide transactions, payments, and foreign exchange, like credit card companies and money changers. None of these are considered ‘banks’.

Here I define a ‘bank’ as an entity that takes deposits from the public and issues its own currency notes that are widely accepted by consumers and businesses throughout society to pay for goods, services, and/or settle debts. Ie ‘banks’ create and issue money.

There were no government-issued currency notes in Australia nor in any of the States before 1913, and no government-issued coins before 1910, so people used bank notes (ie notes issued by the note-issuing commercial banks) as ‘money’ to pay for things and settle accounts.

Today’s diagram shows all ‘note-issuing’ banks in Australia that survived and were merged into today’s big banks. However, the diagram does not include the following:

Failed banks

The diagram shows only those banks that survived to be merged into the current banks we have today. There were numerous other banks and other entities that collapsed and were liquidated – mainly in the economic depressions in the 1840s, 1890s, and 1930s, and also as a result of bad lending in the 1970s and 1980s. I look at some of these banking collapses in other stories.

1890s banking crisis

The most serious banking crisis in Australia was in the 1890s. It was caused by overly aggressive lending to property developers by most of the banks (and many other types of lenders as well). Melbourne was the centre of the wild property lending boom and bank collapses, but it was a national (and global) phenomenon.

The 1890s bank crisis is marked by a vertical grey band running down the middle of the diagram.

Of the 28 note-issuing banks in Australia before the 1890s banking crisis, this is how they fared:

Only 9 banks survived unscathed

Only 9 out of the 28 banks remained open throughout the crisis and survived intact, with depositors retaining access to their money at all times. On the diagram, these are the banks without a black box interrupting their timelines during the crisis.

We can see that each of the current big-3 (Westpac, NAB and ANZ, but not CBA as it was not formed until 1911) had predecessor banks that had ‘black boxes’ – they were forced to close their doors, liquidate, and restructure in the crisis.

Therefore, neither WBC, NAB, nor ANZ can validly claim today that they survived the 1890s bank crisis unscathed.

13 banks were liquidated and restructured

13 of the 28 banks were forced to close their doors temporarily (payments were ‘suspended’, in banking lingo) to prevent depositors from withdrawing their money in the bank runs. These banks were liquidated and restructured into new banks. Shareholders suffered heavy losses and/or were forced to contribute more equity capital to cover losses and re-capitalise the new replacement banks. (The banks had ‘part-paid’, or ‘contributing’ shares, which were called up to put in additional capital in the restructures).

Depositors lost access to their money as the deposits were converted into short-term and long-term securities. Eventually, depositors did get their money back, with interest, in nearly all cases. The notes created out of the restructured bank deposits were listed on the local stock exchanges so that depositors could sell them on the market (usually at discounted prices) if they need cash in a hurry.

For these banks, their suspension, liquidation, and restructures are marked with a black box in their bars in the diagram. I have marked the ‘big ones’ with red circles. We can see that Westpac, ANZ, and NAB each had predecessor banks that went through this embarrassing, painful, and costly process.

The bank collapses, in particular the locking up of more than half of all bank deposits in Australia for more than a decade, deepened and prolonged Australia’s 1890s economic depression.

6 banks closed permanently

6 of the 28 banks closed permanently, were liquidated, and were not restructured or re-opened. Shareholders were wiped out, and depositors suffered heavy losses. These banks are not on the diagram because here I only show banks that survived to become predecessors to the current banks we are left with today.

Dozens more failed

In addition to the 6 note-issuing banks that failed in the 1890s crisis, there were also dozens of finance companies, mortgage lenders, and ‘land banks’ that collapsed as well. I cover the 1890s banking crisis in another story.

Nor does the diagram show banks that failed in the bank crises of the 1830s, 1840s, or 1930s. The diagram does show the one bank that collapsed in the 1970s property construction boom/bust: the Bank of Adelaide (no relation to the current ‘Adelaide Bank’) – taken over by ANZ in 1980. (Shareholders were wiped out but depositors suffered no losses).

Australia -v- USA

It should be noted that bank failures have been relatively rare in Australia, particularly compared to the US, where many thousands of banks have failed in various banking crises.

Other banks and lenders

State government banks are not included here.

Each of the State governments (apart from Queensland which wisely never had a state-owned bank) once had government-owned banks. These were all closed down, mostly as a result of bad debts from bad lending. The good assets were picked up by other banks – mostly the Commonwealth, and the bad debts were retained by the State governments, with the losses borne by tax-payers. The worst offenders were the State Banks of Victoria and South Australia.

Savings banks are also not included here. Many of the big trading banks had their own savings banks, mostly to get around restrictive government-imposed bank regulations following WW2. Following deregulation in the 1980s, the savings banks were merged into the respective trading banks’ operations.

Building societies are also not included here. Most building societies were either gobbled up by the big banks, or they converted into banks in order to obtain cheaper funding to compete with the banks, but they were then gobbled up by the big banks anyway.

Recent batch of micro-banks

The regulators have been trying to revive competition by allowing several micro-banks to obtain banking licences. Most of these will probably be gobbled up by the big banks, as some have already.

There have also been a few smaller and ‘regional’ banks. Most were/are former building societies or credit unions, and most have already been gobbled up by the big banks. Last month (July 2024) ANZ finally obtained approval to gobble up Suncorp Bank, which was originally a Brisbane-based building society.

Australia: land of oligopolies

This pattern of growth via acquisition into oligopoly cartels is not unique to banking in Australia. It is one of the defining features of the Australian economy, and it is one of the factors contributing to our history of structurally higher inflation.

It is also present in most other industries in Australia including - supermarkets, hardware stores, insurance, toll roads, airlines, rail freight, gambling, lotteries, transport, utilities, telecoms, fast foods, packaging, distribution, labour unions, steel, building products, office supplies, petrol, ASX, share registries, cinemas, event ticketing, bottle shops, and many others.

In fact, it is hard to think of many local industries in Australia with true competition – ie with large numbers of relatively small, independent, non-collusive price-takers, with healthy, continuous turnover of weak players failing and new players rising to take their place. Local restaurants, coffee shops are rare examples.

In the case of banking (and other industries), their arguments in favour of competition-lessening take-overs are mainly centred around the need to build ‘scale’ to service Australia’s widely disbursed population over vast distances across our huge land mass.

Another reason is that Australian companies have had an almost universally disastrous track record of trying to expand overseas (banks included), and so their only real option for growth is taking over competitors at home.

‘Four pillars’ protection

Since the remaining big-4 retail banks are all effectively the same (products, services, prices), why don’t they continue to merge into just one or two even bigger banks?

The only reason the banks have not merged further is bipartisan government opposition to further mergers.

In 1990, then Treasurer Paul Keating vetoed a proposed merger between ANZ and life insurer National Mutual. He created the ‘six pillars’ policy – preventing mergers between the four big banks and the two dominant life insurers – AMP and National Mutual.

(I was present at the birth of the ‘six pillars’ policy – I was running ANZ’s acquisition of National Mutual’s small retail bank, ‘National Mutual Royal Bank’, which did go ahead, while the big boys worked on the overall ANZ-National Mutual mega-merger, which was vetoed by Keating.)

Keating saved ANZ from itself!

As it turned out, both AMP and National Mutual suffered huge losses and massive falls from grace. Keating probably saved ANZ by vetoing the ANZ-National Mutual deal because National Mutual’s losses would probably have swamped ANZ’s capital base, which would come under enormous pressure in 1992-3 anyway from the fall-out from the 1990-1 recession following the late 1980s lending frenzy.

(At the time I was CFO of ANZ’s retail bank - ‘Chief Manager Finance & Planning’ reporting to future CEO Don Mercer – the retail bank profits saved ANZ’s bacon. A fortuitous ‘right-time, right place’ moment for me!).

ANZ’s losses were not as bad as Westpac’s, which were near-fatal. However, had Keating allowed ANZ to take over National Mutual, the combined losses probably would have been fatal for ANZ.

(I still have a nice stash of ANZ shares from the early 1990s with cost bases as low as $2.75 per share. I can thank Mr Keating that they did not go up in smoke, and are worth a tidy sum today!)

AMP was eventually allowed to gobble up the remnants of National Mutual in 2010, and AMP has now almost disappeared from sight altogether. The decline of the once-mighty AMP is another story for another day!

The future?

With the demise of National Mutual and AMP, the original ‘six pillars’ policy has now become the ‘four pillars’ policy – protecting the four big retail banks from merging with each other.

Questions for investors and policy makers:

Do the big-4 dinosaur retail banks deserve continued political protection?

Are consumers receiving any real benefits from their so-called ‘competition’?

The big-4 retail banks are all trading at well above their book values and intrinsic values, and that’s without any takeover premium because they are protected from take-over by the ‘four-pillar’ policy. Just imagine the amount of over-pricing and wealth destruction that would occur in the event of a take-over!

For a rundown of the shenanigans and performance of the big banks over the past three decades (including Macquarie, which is a very different beast altogether) see:

· Which Bank? . . is winning the Battle of the Banks? (17 July 2024)

See also:

· Labor’s attempt to nationalise all banks in Australia! (21-7-2024)

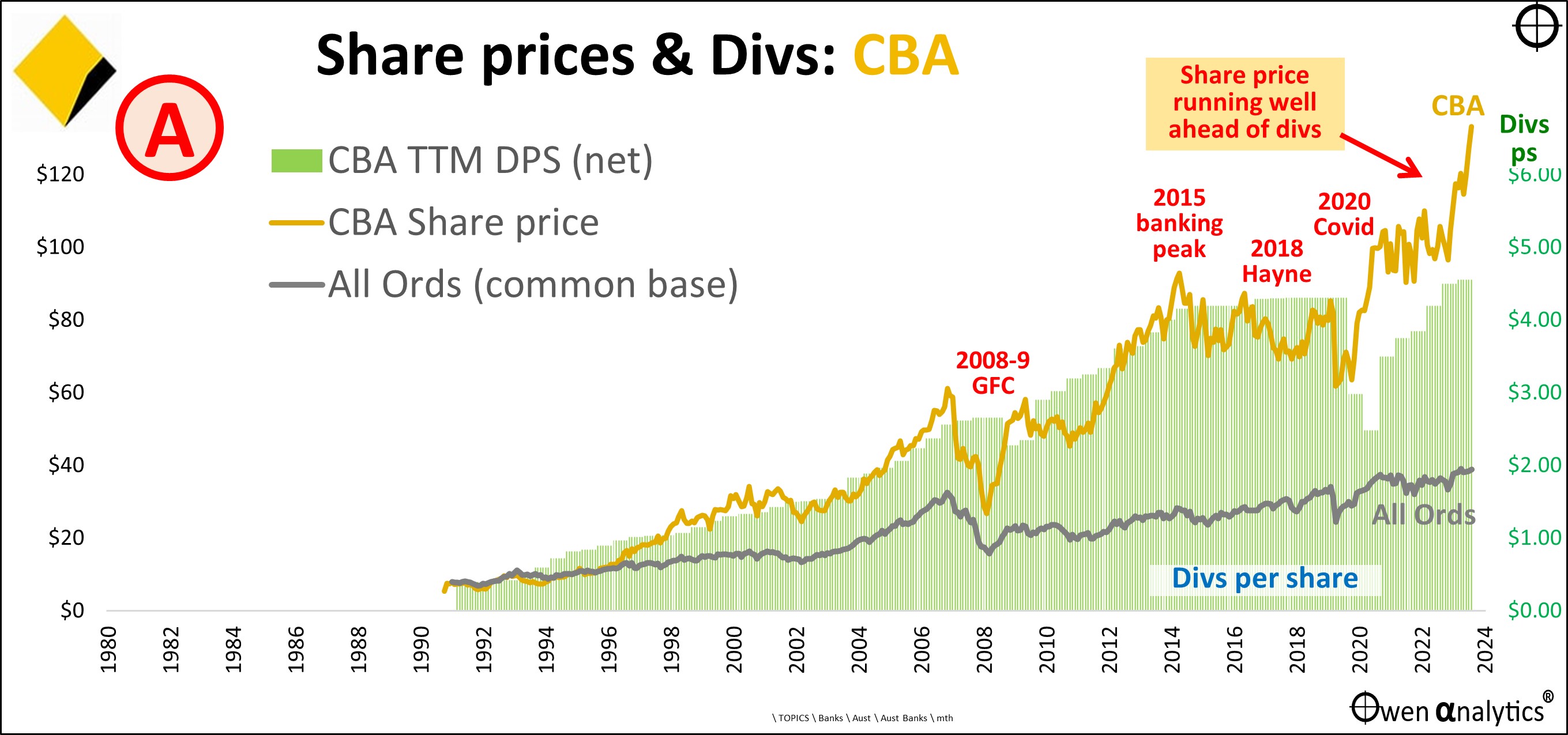

For my take on the current leader - CBA - see:

· CBA in 7 charts – the ‘Steven Bradbury’ of Australian banking – now suddenly a ‘growth stock’? (29 July 2024)

‘Till next time – happy investing!

Thank you for your time – please send me feedback and/or ideas for future editions!

Disclosure: I have been a long-term shareholder in ANZ and Macquarie (mostly from the 1990s), but readers should certainly NOT imply or assume anything from this, as my holdings reflect decisions made many years ago, and this may or may not imply similar decisions today. (I am ‘locked in’ by significant capital gains that would incur CGT if I sold). I was also a senior executive in ANZ running various business units from 1989 to 1998, in the clean-up and recovery from the 1980s lending binge – refer to bio here. I have also been a shareholder in the other three big banks at various times.