Australians have always had a love-hate relationship with their banks. (OK, so it’s mostly hate, I know!) But it was not always the case.

Believe it or not, there was a time when the Australian public loved their banks so much they went to the election polls and kicked out a Federal government that was trying to close the banks down!

Yes, these are the same banks we all love to hate today.

Here is the remarkable tale of banks -v- politics, capitalism -v- socialism. Right here in Australia.

Dislike of banks is not new

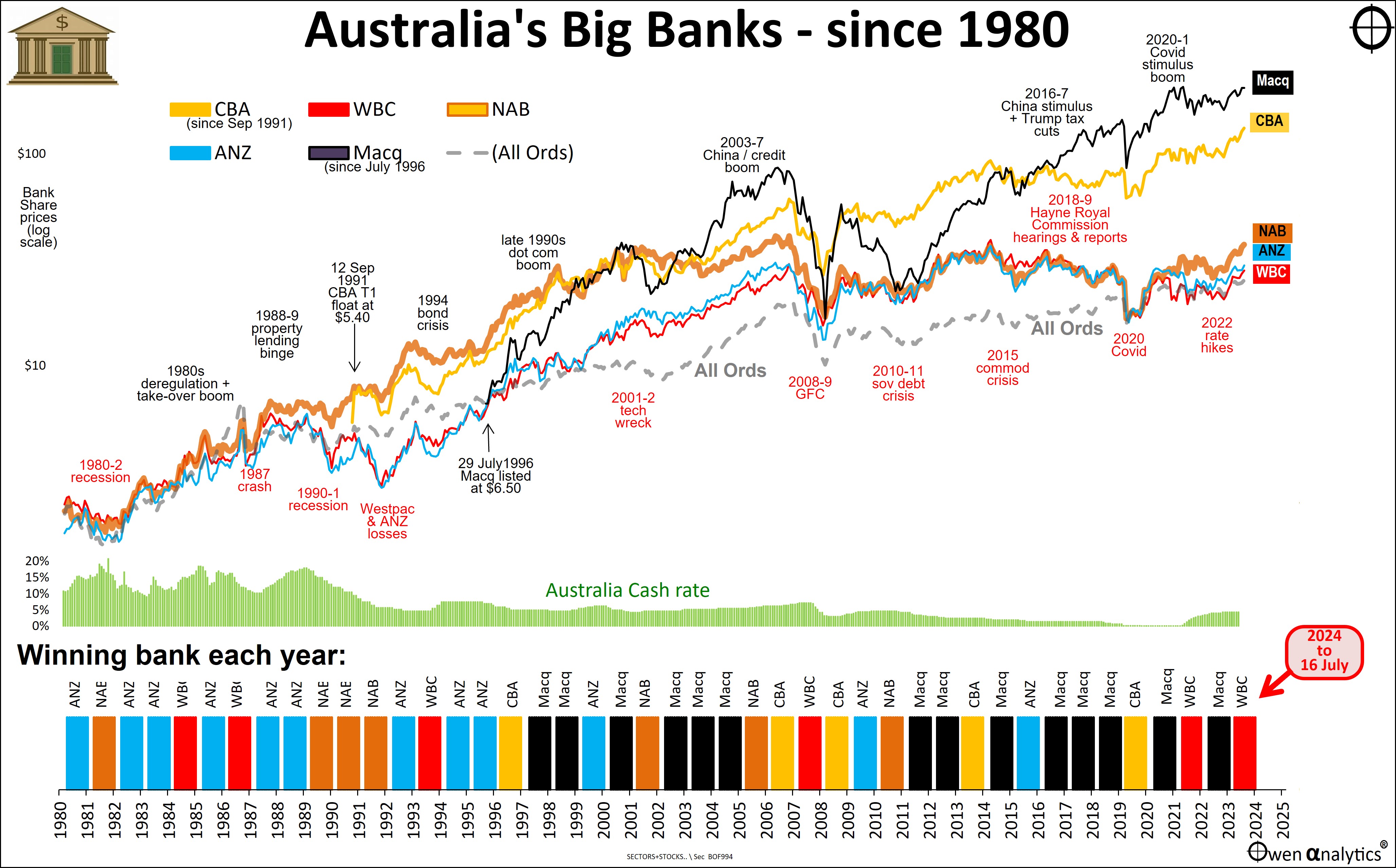

There are times when it seems banks are almost universally on the nose - for example, during and after the 2018 Hayne Royal Commission which revealed a host of illegal and unethical practices in all of the big banks, from board level down to branch staff and every level in between. Or every time we waste half a day trying to deal with bank call centres and get nowhere. Or spend months trying to get a wrongful charge or fee reversed (still trying). Or spend SIX YEARS trying to get the names of accounts corrected to reflect a divorce settlement.

This is not new. Banks have been working hard to earn our dislike and distrust for two hundred years!

Background to the Labor Party’s war on the banks

The banks were blamed (correctly) for prolonging and worsening the 1930s ‘Great Depression’ in Australia by refusing to lend to governments to allow them to deficit spend their way out of the depression. Even the government’s wholly owned Commonwealth Bank refused to lend it money to increase spending to ease the pain on its citizens.

Because of the banks’ blanket refusal to lend, governments were forced to cut spending on welfare and infrastructure programs, and impose nation-wide cuts to wages and pensions.

‘Greedy’ London bankers were behind the crippling Niemeyer ‘austerity plan’ that made Australia’s 1930s depression particularly harsh. British banker Sir Otto Niemeyer was sent to Australia by UK banks to get the Federal and State governments to rein in spending and to repay their debts owed to UK banks and bond holders.

As a result of this bank-imposed austerity, Australia defaulted on its entire stock of domestic bonds (held by Australians) so that the UK debts could be repaid in full to the London banks. Australians suffered so that greedy foreign bankers could be repaid every penny they were owed, on time!

(More about Australia’s government bond default and the 1930s Great Depression in a separate story.)

1890s bank collapses and the Labor Party

Going back even further, the Australian Labor Party was founded in the hardships of the 1890s depression, and one of the enduring policies of the Party was the elimination of non-government-owned banks. For good reason.

Bad bank lending in the 1880s property development and construction boom resulted in widespread bank collapses in the 1890s, inflicting heavy losses and hardships for bank depositors – most of whom were ordinary workers.

Then, the re-imposition of overly strict lending rules by the surviving banks restricted economic growth, deepened the depression and slowed the recovery. One of the Labor Party’s founding philosophies and stated policies was that all non-government banks had to be eliminated, a view widely shared by workers across the country.

The battle began

After the Second World War was over, the number one policy of the Chifley Labor government was to once and for all put an end to non-government-owned banks in Australia – to nationalise them all and to roll them into the government’s wholly-owned Commonwealth Bank.

CommBank was established by the Fisher Labor government in 1911 as a direct response to the 1890s bank crisis. Under Labor’s plan, CommBank would be one giant monopoly bank under the direct control of the Federal government, supplemented by the State government banks.

Given the sheer weight of public dislike and distrust of the banks – for deepening and extending Australia’s pain in the deep depressions of the 1890s and 1930s, it certainly seemed the Chifley Labor government was onto a winner!

Under the war-time controls, the government’s Commonwealth bank had already been given effective control over all non-government banks’ operations, including control over interest rates, lending, deposits, foreign exchange, and even control over bank profits. So it was not seen as a big step from there to simply close them down and merge them all into the Commonwealth Bank.

The government even offered to pay bank shareholders the current price for their shares – so it was not a communist-style confiscation of their shares, as in other countries like Russia, China, Cuba, Vietnam, and Venezuela.

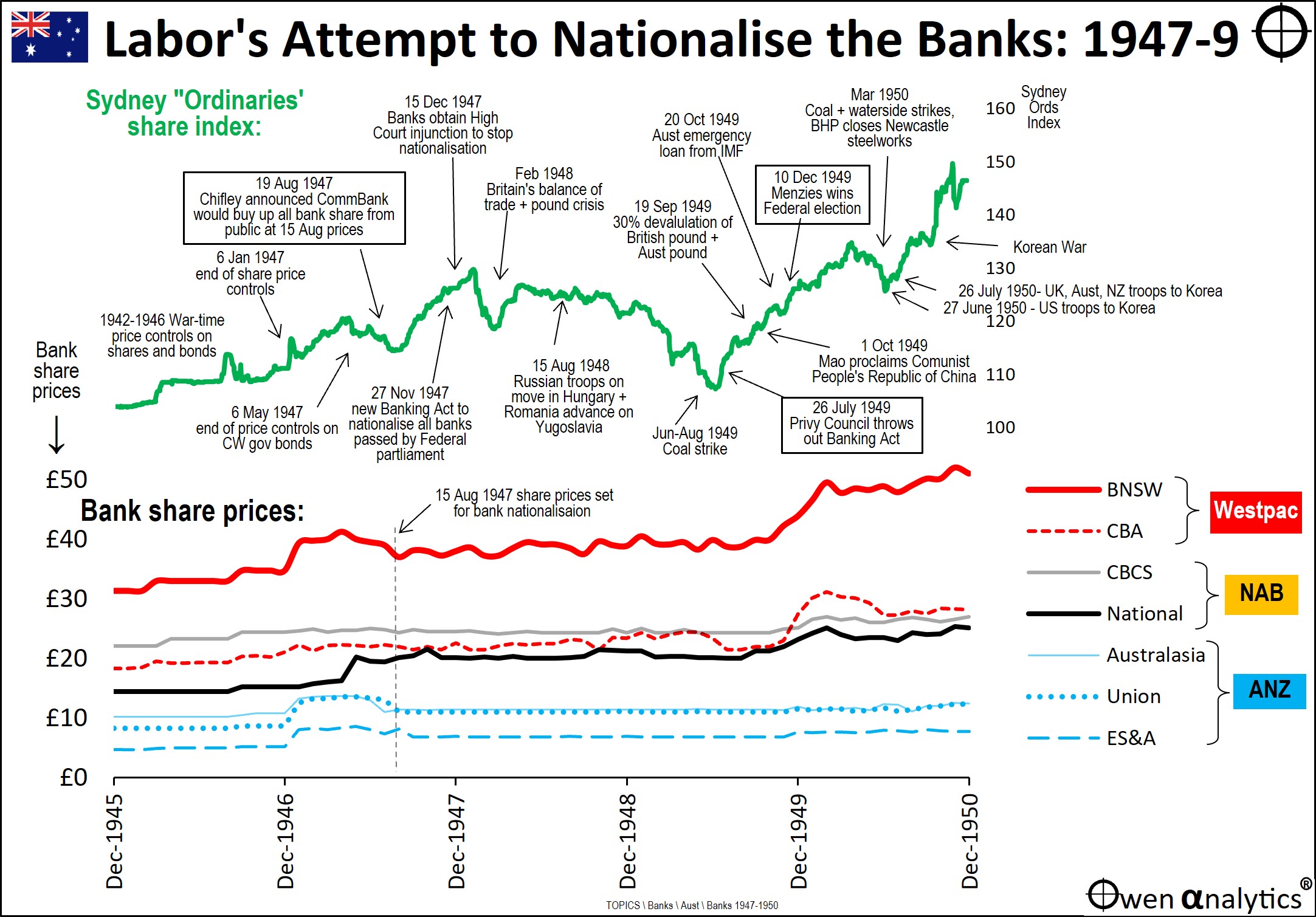

The battle began on 16 August 1947 when Labor Prime Minister Ben Chifley announced the plan to nationalise all banks. On the 19th he announced that the Commonwealth Bank would buy up all bank shares from the public at 15 August 1947 share prices, and the buying started on the 20th.

On 27 November 1947 the new Banking Act, to nationalise the banks, was passed in Federal parliament and became law.

Banks fight back!

But the banks fought back, and won! On 15 December 1947 the banks won an injunction from the High Court to stop nationalisation. That started 18 months of appeals and counter-appeals.

The Banks eventually won in the High Court, and they won the appeal in the Privy Council in London on 26 July 1949. They even won the Federal 1949 election for the Liberal Party over the issue of bank nationalisation. Labor’s 1949 election loss was the start of 23 years in the wilderness for Labor.

We may fear banks, but we fear communism more!

The court battle was about constitutional power, a rather dry and remote topic. But for the general public it was much more than that – it was a battle against fears of rising socialism and communism around the world and in our region.

The end of WW2 marked the start of the new Cold War, with the rise of Soviet bloc in Eastern Europe against the newly formed NATO. In Asia it was the rise of communist China – with Mao Zedong proclaiming the new Communist People’s Republic on 1st October 1949, and communist insurgencies across South-East Asia.

At home, the former union leader PM Ben Chifley even sent in troops to break up the coal miners’ strike in the Hunter Valey. With rising fears of socialism and communism thick in the air, the Liberal Party whipped up fears of Labor’s socialist agenda, resulting in Labor suffering heavy swings against them in state elections in Victoria and NSW.

Electoral victory for capitalism

Finally, in the Federal general elections held on 10 December 1949 (just weeks after Mao Zedong’s Communist victory over China), Bob Menzies’ Liberal/Country coalition won a landslide victory and threw Labour out. Menzies was able to exploit McCarthy-like anti-communist rhetoric to raise fears that Chifley’s bank nationalisation was merely the first step in a broader shift toward socialism or even communism right here in Australia.

It was not a great love of the banks that won the public battle and the electoral votes, it was that banks represented capitalism. For voters, capitalism and banks were better than the fear of socialism or communism, which was rising around the world and in our own back yard.

What happened to bank share prices?

Actually nothing at all. The government promised to pay bank shareholders the 15 August 1947 prices, and CommBank started buying up shares at those set prices from shareholders who wanted out. That put a floor and a ceiling on share prices for the duration of the dispute.

The lower section of the chart shows share prices of the main banks. At that time there were seven main predecessors to what are now Westpac, NAB, and ANZ banks, and I have grouped them together on the chart.

The ‘CBA’ is not today’s CBA (Today’s CBA was government owned until floated from 1991). ‘CBA’ on the chart refers to the Commercial Bank of Australia, which was later acquired by BNSW (Bank of New South Wales) to form Westpac in 1982.

Overall share market

In the upper section of the chart is the Sydney Ordinaries share index (pre-curser to the All Ordinaries), showing how the overall market was rising strongly out of the War, but fell heavily as the banking dispute, and labour disputes in the coal mines and around the country, worsened. The Sydney Ordinaries Index fell -17% from 5 February 1948 to 8 July 1949.

Finally the overall market, including bank share prices, rebounded strongly when Labor lost the court battle in London (26 July 1949), and was thrown out of government altogether in the Federal election (10 December).

Who says banking and politics don’t mix?

Every time we are see misconduct that re-ignites our collective dislike of banks, just think – putting up with rapacious banks on the loose might actually be better than the alternative! Or would it? You decide!

See also:

· Which Bank? . . is winning the Battle of the Banks? (17 July 2024)

Look out for my upcoming story: Australia's banks: Origin of the Species, or 'Survival of the Fattest!'

‘Till next time – happy investing!

Thank you for your time – please send me feedback and/or ideas for future editions!