Quick 2-question Quiz for Aussie bank investors (90% of readers will probably get these wrong!):

Q1 Which of the big Aussie banks has had the largest % share price gain this year (calendar 2024 to date)?

CBA’s extraordinary share price rise has certainly grabbed all the media attention this year, but it is not CBA!

Q2 Which of the big banks has been the best for shareholders over the past one, two, and three decades?

CBA is also frequently held up as the best of the big banks in recent decades on share returns, but that is not true either!

Best bank by share price gains per year.

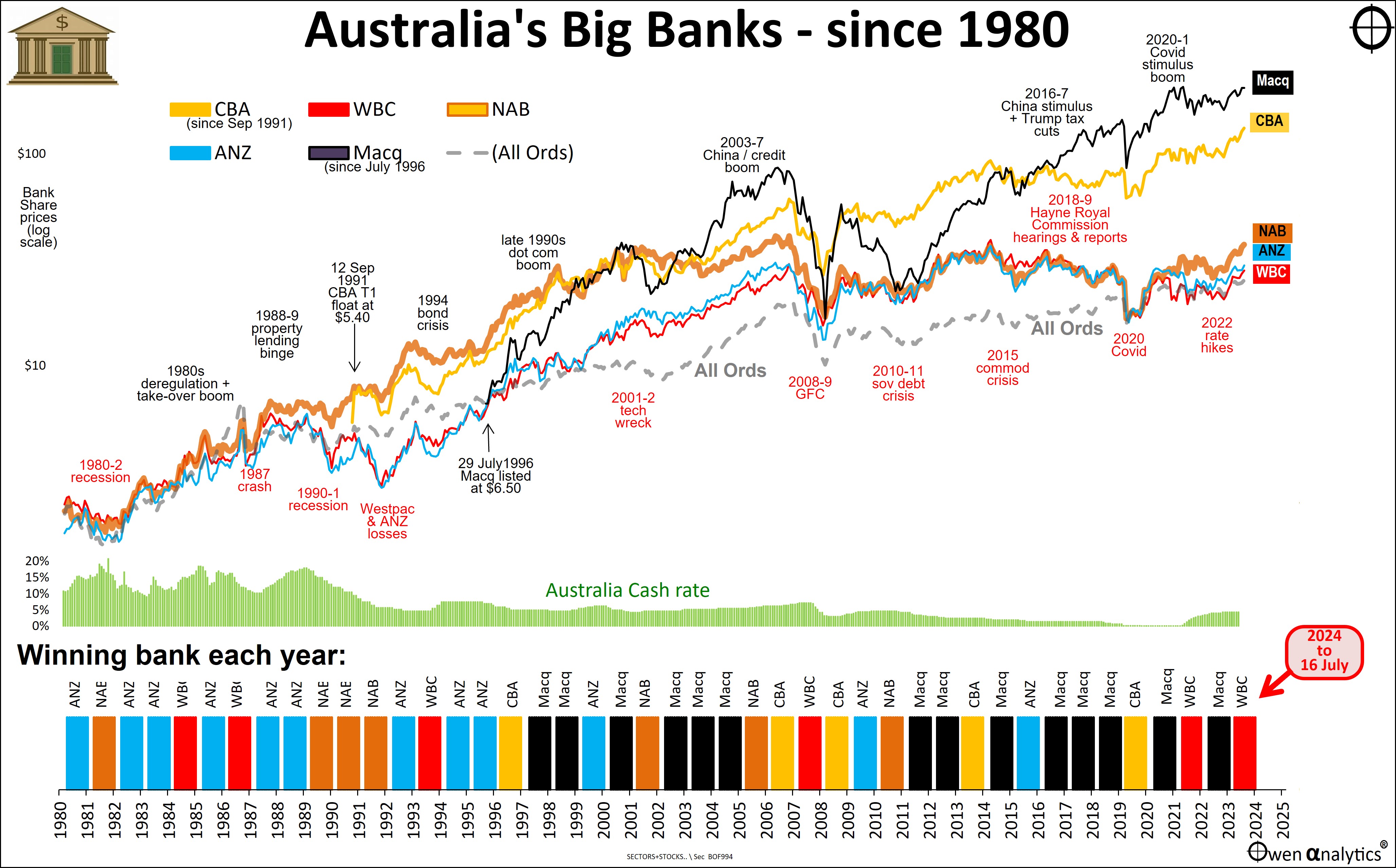

In today’s chart, the upper section shows the share prices of the big Aussie banks since 1980 (in the case of CBA and Macquarie, since their ASX listings in 1991 and 1996 respectively).

The middle section (green) shows cash rates during the period – reducing from 20% in 1982 (triggering the early 1980s recession), and 18% in 1989 (triggering the early 1990s recession), down to 0.1% during Covid, and 4.35% today.

(A reminder that today’s cash rate is actually rather low in the scheme of things, especially since inflation is still well above target.)

The coloured bars in the bottom section show the winning bank (by share price gains) each year since 1980.

Winner for 2024 (to date)?

The winner this year (2024 to 16 July) is Westpac: up +23.1% this year, beating CBA +18.5%, NAB +21.8%, ANZ +14.9% and Macquarie +11.5%.

As to the second question in today’s quiz – which has been the best big bank in the past one, two, and three decades?

The answer is Macquarie – winning in 11 out of the past 26 years (black bars in bottom section of the chart), and in seven out of the past 12 years. It has beaten even CBA, but has been far more volatile. (More on Macquarie below).

Game of two halves

The four decade period in today’s chart can be divided into two halves. In the first half the banks as a group thrived (despite stumbles from Westpac and ANZ), but in the second half they stalled.

During the first half we see the phenomenal rise of NAB (orange) and CBA (yellow), soaring well ahead of the overall market (All Ordinaries Index, grey dashes), and even further ahead of Westpac (red) and ANZ (blue).

In this first half of the period, there was an extraordinary changing of the guard: NAB went from being the smallest of the four banks to the largest, leapfrogging the others. How? Simple - by doing fewer dumb things!

Meanwhile, Westpac (red) and ANZ (blue) had a huge stumble, posting massive, near-existential bad debts and losses from the early 1990s recession as an inevitable result of their mad (and bad) lending sprees in the late-1980s deregulation boom. (I cover the early 1990s recession and bank crisis in a separate story.)

We can see from the chart that the share prices of Westpac (red) and ANZ (blue) have been in virtual lockstep during the entire period, although they had very different histories.

Westpac

Westpac was formed in 1817 as the Bank of New South Wales (the ‘Wales’) as Australia’s first locally owned bank and its first local incorporated company. It survived several near death crises in the first few decades of its life but emerged as Australia’s largest bank for most of the two centuries since formation.

Westpac was always a Sydney-based bank. Sydney may have been the first colony, but it was not where most of the money was for much of the time. For most of the century following the 1850s Victorian gold rush, and then the 1880s Broken Hill silver-lead-zinc boom, the largest and wealthiest city was Melbourne, and Melbourne was financed mainly by British investors via British banks.

ANZ

ANZ is the result of a merger of the three ‘Anglo’ banks that were formed and owed in London to raise English and Scottish money mainly for Melbourne - the Bank of Australasia (1835), the Union Bank (1837), and the English, Scottish & Australian Bank (1852).

ANZ (the merger of the three ‘Anglo’ banks) was always the weakest of the big banks, it had to resort to more aggressive lending, and had lower capital levels (and usually higher gearing) than the others. It is still the weakest today, nearly two centuries later.

This was unfortunately pointed out by current CEO Shane Elliott this month after finally ‘winning’ regulatory approval for the over-priced, earnings-depleting, value-destroying takeover of Suncorp. Elliott admitted that ANZ was closer in size to Bendigo Bank than CBA. Ouch! He will not last long with statements like that!

NAB overtook Westpac and ANZ by doing far less dumb lending

NAB was a product of the newly-found nationalist pride on the Victorian gold fields during the 1850s gold rush. Its name ‘National’ was a deliberate dig at the foreign owned and controlled British colonial banks (now ANZ).

Before bank deregulation the 1980s, NAB was the smallest and quietest/sleepiest of the big banks. The more aggressive Westpac and ANZ were the worst offenders in the wild lending binge of the late 1980s following deregulation, while NAB and CBA sat back and mostly watched the mayhem from the sidelines.

As a result of the Westpac and ANZ losses from the early 1990s recession, NAB suddenly found itself leap-frogging the others into top position as the largest and most profitable bank in Australia.

Commonwealth Bank

CommBank was established by the Fisher Labor government in 1911 as a direct response to the 1890s bank crisis, which was caused by a monumental frenzy of bad lending by the commercial banks, primarily to property developers mainly in Melbourne. The resultant banking collapse in 1893 sent Australia into a deep and long economic depression.

Commonwealth Bank was to be a government-owned ‘safe-haven’ bank for people’s savings, away from the perceived avarice and greed of the commercial banks. (A century later of course, it was the Commonwealth Bank itself that was to become the epitome of bankers’ avarice and greed!)

Under Labor’s grand plan, CommBank would be one giant monopoly bank under the direct control of the Federal government, supplemented by the ‘safe’ State government banks. How did that grand plan turn out? The Chifley Labor government’s attempt to nationalise all commercial banks and consolidate them all under CBA eventually failed in 1949. The reformist Hawke/Keating Labor government privatised the CBA and sold it off to the public from 1991.

What was left of the ‘safe’ State government banks blew themselves up in the early 1990s bank crisis. Taxpayers in Victoria and South Australia are still paying for the losses today. (There is only one thing worse than bad lending by private commercial banks – and that’s bad lending by government-owned banks!)

(I will cover the 1893 bank crisis, and the failed nationalisation of banks in separate stories.)

The second half

In the second half of our four decade review there are two main themes: (1) NAB entirely squandering its lead, and (2) the overall flat-lining of the big-4 banks – the end of the golden era for banks.

NAB woke up and started doing dumb things!

Alas, NAB’s lead over the other banks did not last long. After the dust settled on the huge losses from the 1990-1 recession, the banks went mad once again (including and especially NAB this time), embarking on wild spending sprees on failed overseas adventures.

NAB completely squandered its lead and by the late 2010s was relegated to the smallest of the ‘big-4’ once again. How?

NAB was sensibly and fortunately asleep during the mad 1980s lending frenzy, but CEO Nobby Clark and his side-kick (and replacement CEO) Don Argus mistook their own sloth for brains.

Clark and Argus suddenly thought they could teach the British how to do banking in Britain (!) so they bought up retail banks across northern Britain. They also arrogantly thought they could teach the Americans how to do mortgage lending in America (!!) so they bought up Homeside in the US.

Westpac also went mad buying up banks in the US, hoping to beat the Americans at their own game on their own turf! Westpac’s grand plan was to be “Australia’s World Bank”! Why not?

Meanwhile, ANZ had bought up a network of banks all over Asia and Africa in the early 1980s (Grindlays) in an attempt to ‘get big’ before deregulation, to compete with Westpac (which bought the Commercial Bank of Australia in 1982), and NAB (which bought the Commercial Banking Co of Sydney in 1983).

ANZ ended up dumping the Grindlays network in the 1990s because it couldn’t figure out what to do with it! Then ANZ spent the 2000s in yet another failed attempt to get back into Asia under Mike Smith (ANZ, a regional ‘super-bank!’), but retreated to Australia once again under Shayne Elliott. Both a complete waste of time and money.

Overseas failures

Each of these ego-driven overseas adventures by NAB, Westpac, and ANZ wasted billions of dollars of shareholders’ money, but they did provide bank directors and executives with endless ‘free’ (shareholder funded) travel, entertainment, and perks (which, after all, was probably the main motivation in the first place).

After failing dismally overseas, the big-4 banks turned their attention to buying up insurance companies, fund managers, financial planning groups, and mortgage brokers at home. The idea was to ‘cross-sell’ their conflicted, over-priced, internal products to their unsuspecting bank customers.

Most of these ‘no-core’ cross-selling businesses were hugely profitable for the banks but the rampant greed and dishonesty in their aggressive selling practices were eventually exposed by the Hayne enquiry (below).

End of the golden years of banking

During the first half of the past four-decades, each of the big-4 banks, even the beleaguered ANZ and Westpac, managed to beat the overall market benchmark (All Ords index, grey dashes on the chart) thanks to their price-gouging oligopoly.

In particular, the twenty years from 1994 to 2014 were golden years for the banks. Bank shareholders have benefited tremendously from the cartel monopoly price gouging, gobbling up of nearly every small competitor, lax controls, sleepy regulators, and notably, an almost unbroken run of economic growth.

This twenty-year period of good times enabled the banks to get lazy and fat on a bewildering array of institutionalised greed, fraud, fee gouging, miss-selling of inappropriate products, predatory lending, over-charging, document forging, market rigging, lying to regulators, facilitating money laundering on a grand scale, terrorist financing, and a host of other dishonest bank practices have lined the pockets of bank staff at every level from the boards of directors down to local branch tellers. (I didn’t make this up – it is all laid out in horrible detail in the 1,069 page Hayne report here.)

After lining the pockets of insiders from the proceeds of their cartel price gouging and illegal practices, there were enough crumbs left over to shower shareholders with windfall profits and dividends.

This predatory cartel structure has turned the financial sector in Australia into a notoriously high paying industry relative to its contribution to society.

End of the gravy train

Cracks started to appear in 2014 with a series of revelations about sharp and unsavoury practices in various parts of various banks – especially the CBA. This turned into a flood of revelations of an extraordinary array of activities across each of the big-4 and other institutions (including AMP), exposed in public hearings during the Hayne ‘Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry’ in 2018, and the final report in 2019.

The range of sharp and unsavoury practices was breathtaking – and extended from the boardrooms to front-line branch staff. The CEOs and boards brushed the charges off as just a few isolated ‘bad apples’, but it was clearly institutional – from top to bottom.

In the words of Commissioner Hayne, the root cause was: “greed – the pursuit of short-term profit at the expense of basic standards of honesty. . . . from the executive suite to the front line.” He was just as critical of the regulator ASIC, which was asleep on the job and reluctant to pursue offenders.

Hayne (and the sleepy regulators, had they been awake) did have the opportunity to ‘break up’ the big banks, like Roosevelt did with US banks in the 1930s, but the banks held far too much political power here. The Hayne findings were extraordinary, but nobody went to jail as far as I know. A few CEOs, chairpersons, and execs took the fall (with fat payouts of course), but life pretty much went on as usual in the old cartel. The banks are still rigging markets to line their pockets today (Hello ANZ!)

Little more than bloated building societies now

Not only have the big-4 given up (hopefully) on their ego-driven overseas adventures and non-core businesses, they have also given up on the basic core role of commercial banks – lending to business.

Westpac, NAB, and ANZ (and their predecessors) all started out as proper commercial banks – with their primary function being short-term lending to business. That’s what banks do – short-term cash flow lending to businesses, funded by short-term deposits.

On the other hand, long-term lending to business (generally secured by long-term assets like real estate) is traditionally done by institutions with long-term liabilities like life offices and pension funds. Consumer mortgage and personal lending was traditionally done by building societies and credit unions with strong links to their local communities.

However, following bank deregulation in the 1980s, and especially since the experience of the enormous bad debts from the late 1980s business lending binge – mainly to property construction and highly-geared takeover cowboys, the banks have now retreated to being primarily home mortgage lenders.

The existing building societies, under pressure from the big banks, turned themselves into banks to get cheaper wholesale funding, but most ended up being bought by the greedy big banks to reduce competition and gouge margins.

Today, the big-4 banks are essentially little more than bloated building societies, but with ludicrously over-paid executives and staff.

The problem is that more than half of the housing lending in Australia is done by mortgage brokers who just shop around for the best deal on the day. As a result, although most home loans are technically on a bank’s balance sheet, the borrowers have no loyalty to one bank or another – the only loyalty is to lender with the lowest rate while it lasts.

That’s no way to run a business. Banks are almost universally hated by their customers. The only reason people don’t switch banks is because they know all banks are the same!

Half the capital and a quarter of the brains

Why retreat to housing lending instead of real banking? Because housing lending requires half the capital and a quarter of the brains than business lending!

With commercial banks retreating, lending to business is now mostly done by ‘private credit’ funds – ie non-bank lenders, with less regulation and no loss-absorbing capital, with funds provided mainly by super funds and high-net-worth wholesale investors, bypassing the banks altogether.

Flat-lined since 2014 heyday

The chart highlights the fact that the share prices of the big-4 banks peaked a decade ago and have essentially flat-lined ever since. Profitability has been weighed down by enormous costs of fines, regulatory penalties, remediation, and compliance, plus requirements for higher levels of capital.

Share prices going nowhere for a decade are bad enough – but that’s before inflation!

CBA’s recent price surge has taken it just above its March 2015 peak, but Westpac and ANZ are still below their early 2015 peaks, and NAB is still below its pre-GFC peak. A decade of no nominal growth, and serious negative real growth (after inflation) is dismal.

The future?

The future of the local bloated cartel home loan banks, and whether they are over-priced given their dim prospects, is another story for another day – stay tuned!

Macquarie

Meanwhile, the best of the big banks by far has been Macquarie, albeit with much higher volatility.

I include Macquarie as a ‘big bank’ here because several times in recent years Macquarie has overtaken the smallest two of the ‘big-4’ to sit in the middle of the ‘big-5’ in terms of market value. At the moment it is sitting just behind ANZ.

In Australia the ‘big-4’ is now the ‘big-5’.

Macquarie is different

Macquarie is very different from the others. It has a banking licence, but it is mainly an asset-shuffler and ticket-clipper, that manages to stay nimble, and somehow stay one step ahead of the law (most of the time anyway). Paying fines and penalties for illegal activities and misconduct is just a cost of doing business. Their operating model is essentially: ‘Do whatever you like, just don’t get caught!’ (So it’s similar to the other big banks, just more brazen.)

It has been run by a succession of cunning and wily operators who have stayed ahead of the game, quickly adapting to suit the times, exploiting loopholes and weaknesses wherever and whenever they can find them. It has always been an innovator that developed new markets for itself rather than compete head-on with the traditional banks.

Macquarie did have a genuinely good product in the 1990s – their market-leading Cash Management Trust. These days a general warning would be: Never, ever, EVER buy anything from Macquarie – you WILL get ripped off. That’s what they do.

As a shareholder, at least you get to share in some of the crumbs left over after the execs have lined their pockets from their skullduggery. Shareholders learn to close their eyes, hold their noses, and put out their other hand to take the dividends. Best not to know or think about where the money came from and at what cost.

Actually, Macquarie is not really ‘Australian’ - it’s a local offshoot of a British merchant bank, Hill Samuel, that was also formed in the 1830s in London (like ANZ’s predecessors). Hill Samuel tipped in $4m in 1969 to fund the local operation run by Aussie David Clarke, and it was listed on the ASX in 1996.

Rare global success story

Despite its British origins, to the extent that Macquarie has been built by local management here in Australia, it is one of the very few ‘homegrown’ Australian businesses that has succeeded globally. But it has certainly been a rollercoaster ride.

It nearly blew itself up in the GFC with its fancy structured products and tricky paper-shuffling deals. It narrowly survived the GFC and cunningly used the tax-payer backed government guarantee to buy up cheap operations overseas, instead of lending to local businesses hit by the GFC as was the intention of the government support. (The GFC also hit the big-4 retail banks hard, with Westpac and NAB requiring emergency funding from the US Fed).

Macquarie has been the clear winner since its ASX listing in 1996, far exceeding even CBA. Westpac and ANZ never fully recovered from the early 1990s, and are still lagging badly.

But things can change – as history has shown time after time. The key is usually not what they do, but what they don’t do – the winners are the ones that do fewer dumb things!

So - the answers to our quick quiz? – Not CBA and CBA. Its Westpac and Macquarie! Top marks it you got both correct!

‘Till next time – happy investing!

Thank you for your time – please send me feedback and/or ideas for future editions!

Disclosure: I have been a long-term shareholder in ANZ and Macquarie (mostly from the 1990s), but readers should certainly NOT imply or assume anything from this, as my holdings reflect decisions made many years ago, and this may or may not imply similar decisions today. (I am ‘locked in’ by sizable capital gains that would incur CGT if I sold). I was also a senior executive in ANZ running various business units from 1989 to 1998, in the clean-up and recovery from the 1980s lending binge – refer to bio here.

As always, my analysis is fact-based and intended to be as dispassionate as possible, regardless of whether or not I am a buyer, a seller, or holder. This quick, initial snapshot is no substitute for more detailed research.

This is intended for education and information purposes only. It is not intended to constitute ‘advice’ or a recommendation to buy, hold, or sell and stock or security or fund. Please read the disclaimers and disclosures below.