This week, Woolworths CEO Brad Banducci was forced out (suddenly ‘retired early’), after heated public and political backlashes over Woollies’ high margins and profits while customers, suppliers, and staff are being squeezed by the ‘cost of living crisis’ caused by inflation and rising interest rates.

This story is about the difficulties of balancing the interest of owners versus other key stakeholders.

‘Wide moat’

Investors spend their lives searching for companies with a ‘wide economic moat’ – a term popularised by Warren Buffett.

These rare companies have strong and durable competitive advantages, due to high market share, lack of competition (monopolies), or at least friendly/pretend competition (oligopoly cartels), so they have pricing power over their suppliers and customers, resulting in above-average profit margins and returns on equity.

That is certainly what Woolworths is, but the CEO was forced out. What is going on?

There were also some other key factors in play – in particular, Banducci’s somewhat cumbersome (or least sub-optimal) handling of the price-gouging allegations with media, regulators, and politicians.

There were also some other unsavoury scandals on his watch – including the 2016-9 ‘milk wars’ with embattled dairy farmers, the $500m ‘wage theft’ scandal in 2019-20, and public outrage in 2021 over attempts to open bottle shops in Darwin to target aboriginals.

Of course, he could validly argue that these were all done to maximise profits to the company’s owners.

However, it highlights the very fine balancing act - maximising returns to owners while retaining positive relationships with suppliers, staff, and customers – especially with such a high profile company.

Who are the owners?

Who are the company’s owners? A large proportion self-managed super funds, the vast majority of members in public and industry super funds, and everyone who owns an Australian share ETF (exchange traded fund). Therefore most Australian adults are the owners of Woolworths.

Let’s take a look at the company, and how it got to where it is today.

Woollies 1

Woolworths was originally listed on the Sydney Stock Exchange in 1924, when it opened its first store in Sydney (under the Strand Arcade, George Street, where JB Hi-Fi is now). Over the next half century, Woollies grew to be the largest nationwide supermarket chain, via internal growth, and buying up competitors.

The company ran into trouble in the 1980s, with poor inventory management, high costs, high debts, and a price war with arch-rival Coles. (I will cover Woollies 1 in another story).

1980s troubles and take-over play-thing

After Woollies posted losses and cancelled its dividend in 1988, the corporate raiders smelled blood. Ron Brierley’s IEL bought it in 1989 for $1.3b and de-listed it after a battle with the corporate regulator. IEL on-sold the company to another raider, John Spalvins’ Adsteam.

When IEL and Adsteam collapsed under mountains of debts in the 1990-1 recession, Woollies was one of the many companies sold off and re-floated in the liquidation.

The raiders had stripped Woollies of cash, which they siphoned off to pay their debts, but they did get manage to get the people right.

They hired Paul Simons as Chairman (a Woollies veteran who had left to run the very successful Franklins supermarket chain), and they hired Harry Watts as CEO. Simons and Watts pulled off a spectacular turnaround to profits, assisted by the economy recovering from the deep 1990-1 ‘recession we had to have’.

1993 refloat – Woollies 2 – largest IPO in Australia

Thanks to the dramatic turn-around to profitability by Simons and Watts, the re-float in 1993 was a huge success. It was the largest ever float in Australia’s history up to that time, raising $2.45b at $2.45 per share.

IEL made a $1.1b profit on the re-float, but then spent the next decade in the courts fighting claims from the Tax Office for more than $3b in taxes.

Since the 1993 re-float, Woolies’ shares have beaten the overall market by an average of 4% pa, or 5% pa above the market after adjusting for the spin-offs of SCA Property Group in 2012 (69 shopping centres), and Endeavour in 2021 (pubs, pokies, bottle shops).

We look into share price performance a little later.

Avoid doing ‘dumb things’

Another of Buffett’s golden rules is that investing is not so much about being a genius, but about not doing dumb things. This applies not just to individual investors, but also to company boards when investing shareholders’ funds.

As Australia is a remote, sparsely-populated rock in the middle of nowhere, Australian companies have always been tempted to expand overseas. Almost all of their grand overseas adventures have ended in failure, huge write-offs, and losses. Overseas expansion has been a perennial graveyard for over-ambitious Aussie companies.

Sensibly, Woolworths resisted the temptation to expand overseas. Instead, it grew by expanding into other sectors of the retail market here at home. This has been patchy.

Alcohol and gambling

Woollies first expanded into selling alcohol in 1960, accelerating rapidly from 2004 to became the largest owner of bottle shops, licenced hotels, and poker machines in Australia.

This was highly profitable but the reliance on alcohol and gambling revenues also ran afoul of ethical investment funds, and the ‘ESG’ movement.

The bottle shops, pubs & pokies were spun off into a separate listed company called Endeavour Group (EDV) in June 2021. Woollies shareholders received one EDV share per WOW share, so they could decide for themselves what to do with the proceeds of alcohol and gambling.

Fossil fuels

Likewise, Woollies expanded into petrol retailing from 1996 in a joint venture with Caltex (now rebranded Ampol). This has done reasonably well, but is also on the nose with ethical/ESG investment funds as it profits from fossil fuels.

Big W problem

‘Big W’ has been a perennial problem, trying to compete with Coles’ Target and Kmart in the down-market general merchandise market.

Ironically, Woolworths and Coles both started out as general merchandisers before they switched focus to self-service food & groceries in the post WW2 suburban shopping centre boom.

Woollies has failed to either turn around or off-load the troublesome Big-W, despite decades of trying.

Hardware folly

The biggest mistake to date has been its failed, and very costly, attempt to expand into hardware retailing, trying to beat Wesfarmers’ Bunnings at its own game on its home turf. This experiment was started in 2009 and finally closed down in 2016, costing shareholders billions, and also proving a big distraction for management time and effort.

They learned the hard way that they couldn't out-Bunnings Bunnings!

CEOs - patchy

Woollies has had a mix bag of CEOs. Most of them have certainly not been inspired world-beaters.

It started badly when Harry Watts, CEO for the turn-around and 1993 re-float, died while playing golf with Greg Norman just four months after the re-float.

The board had no succession plan and hastily promoted Reg Clairs to CEO. He was supposed to remain until June 1999 but his continual lobbying of analysts and shareholders for an extension annoyed the Chairman, lawyer John Dahlsen, so much that he terminated Clairs six months early, much to the dislike of shareholders.

The replacement CEO, Roger Corbet, was seen as too old to start with, and he had no supermarket experience. He was much less aggressive than Clairs on costs or marketing, but he did lead the acquisition of Australian Leisure & Hospitality (pubs and pokies).

Dumb things

The big problems started with Corbett’s replacement CEO, Michael Luscombe, appointed in October 2006. He started a price war with Coles.

Why start a price war with your oligopoly cartel partner? What was he thinking? Did he not learn from the 1980s price war between the same Woolworths and the same Coles?

Luscombe also initiated the disastrous Masters and Home hardware ventures to try to take on Bunnings.

Luscombe’s replacement CEO from February 2016, Grant O’Brien, threw even more money at the hardware store failures and continued the price war with Coles and Aldi to try to win back market share.

After profit downgrades and share price falls, O’Brien was replaced as CEO by Brad Banducci in February 2016.

Banducci had no supermarket experience either, having come from the bottle-shops, but he did a pretty good clean-up job, closing down the Masters stores, selling Home Timber & Hardware to Metcash’s Mitre 10, and spinning off Endeavour.

However, he had little success turning around or selling Big-W, and he presided over the ‘milk wars’, the $500m ‘wage theft’ allegations, and Darwin bottle shop debacle.

New CEO

The new CEO taking over from Banducci is Amanda Bardwell. Like several past Woollies CEOs, she also has no deep supermarket experience. Her background has mainly been in running (successfully) Woollies online sales, and previously, bottle shop online sales.

Will she succeed? Probably – If she can avoid doing dumb things!

Woollies should be able to maintain high profitability via its predatory oligopoly pricing power, which should support steadily rising profits and dividends, but it needs more than mediocre management to stay focused, milk the cartel, and avoid unnecessary diversions and public and political backlashes that brought about Banducci’s early exit.

Share price performance

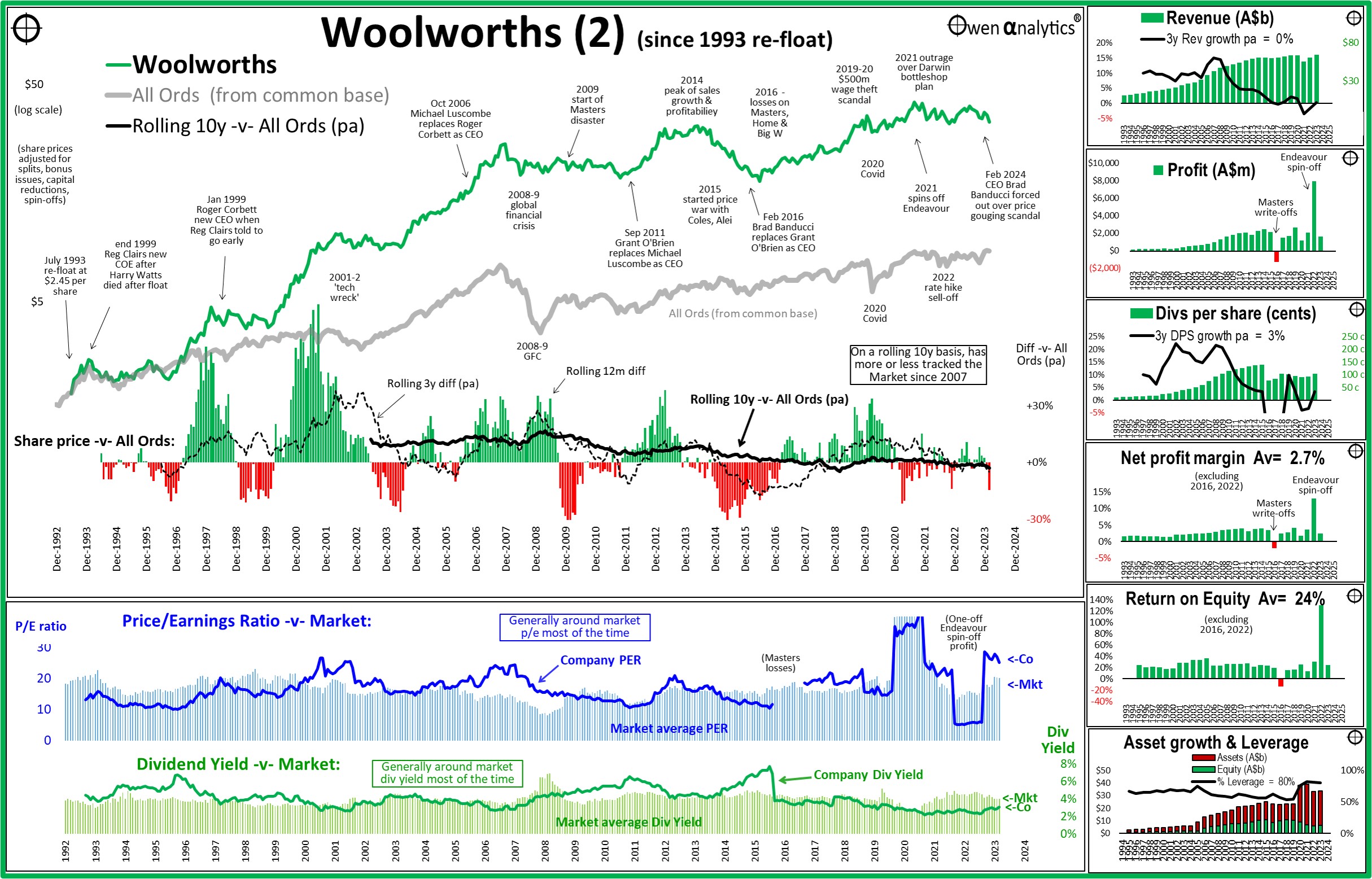

The main chart shows that Woollies (green line) has beaten the overall market (grey) since the 1993 re-float.

The problem is that this out-performance was all in the early years from 1993 to 2007 under CEOs Reg Clairs and Roger Corbett.

Since then, the share price has more or less tracked square with the market.

Rolling 10-year

The heavy black line in the lower section of the main price chart shows rolling ten-year share price performance relative to the broad market. This is my main test of a company’s share price for long term investors.

I can handle short-term and medium term under-performance (rolling 12 month and rolling three years), but I want to see it beat the market over successive rolling 10 year periods. This is a very tough test that very few companies pass, as it requires a company’s out-performance to continue despite changes in CEOs, chairpersons, and changes in market conditions, competition, etc.

(The black rolling 10-year line starts ten years after IPO).

Here we can see that the black 10-year returns were above the market in the early years but has been flat with the market since 2017 (ie it has tracked the market since 2007).

Pricing – cheap or expensive?

The long chart below the main chart shows pricing relative to the overall market – on two measures: price/earnings ratios (blue), and dividend yields (green).

As a mature, defensive, incumbent staples retailer, ordinarily it would be expected to trade more cheaply than the overall market (lower p/e, higher dividend yield). Pricing ratios for defensive staples should usually be lower in booms, and higher in busts.

However, due to its oligopoly cartel with Coles which has resulted in its ability to extract healthy margins and consistently above-market returns on equity, it has more or less traded around market average p/e ratios and dividend yields, overall.

Strangely for a mature, defensive staples retailer, it has traded as more like a growth stock during market booms (higher p/e and lower dividend yield) – in the late 1990s 'dot-com', the 2005-7 pre-GFC boom, and in the 2019 pre-Covid boom.

The good news is that the share price did hold up better than the broad market in the sell-offs, as a mature, staples retailer should.

To the right of the lower chart we can see that the current pricing is expensive relative to the broad market – ie higher p/e ratio and lower dividend yield.

Is this justified?

Fundamentals

We started by looking at the share price because that is what most investors, and media commentators do. However, for serious investors, the share price is the last thing to look at.

The starting point is the company’s fundamentals.

The smaller charts are a quick snapshot on some of the company’s key numbers, which are the starting point for fundamental analysis. Investors should, of course, delve much deeper into the numbers than this quick snapshot.

Slow decline and decay

It is mainly a picture of decline and decay since the early ‘growth’ years since the 1993 re-float.

Revenue growth rates (top chart) have been slowing steadily over the past 30 years. This is partly due the sale of Endeavour (2021), but the steady slide downward started long before that.

Profits (second chart) – Media, consumer groups and politicians have highlighted the headline profit number (“Billion dollar profits!”) – but we can see that profits peaked a decade ago. (The high bottom-line profit in 2022 was profit on the one-off sale/spin-off of Endeavour).

Dividends per share (third chart) also peaked a decade ago – prior to the hardware store debacle.

Net profit margins (fourth chart) rose in the early years under Clairs and Corbett, but have declined since then.

Media hype over margins

Recent media attention has focused on the latest numbers showing supermarket gross (not net) margins increasing to 6% while consumers are under cost of living pressure.

That is true, but most of that increase in margins came from online sales - under new CEO Bardwell – where costs are lower because the online division has less staff and premises.

The natural counter to that would be for consumer groups and politicians to say: “You say that profit margins on online sales are naturally higher than on physical supermarket sales. Why should they be? Why don’t you pass on the savings of lower costs to consumers?”

Bardwell will need to come up with a good answer to that one.

Returns on Equity

Returns on equity (fifth chart) show the same pattern as the other fundamentals – declining since the pre-GFC years.

However, it is important to point out that the returns on equity of 20-25% are still well above the market average, thanks to the company’s entrenched pricing power.

Political pressure

It is unfortunate that the PM Anthony Albanese has been vocal in the recent price-gouging affair, but he has ruled out breaking up the company to end its market power.

Whenever a politician (from any side of politics) ‘rules out’ something, it inevitably means the opposite.

The new CEO certainly needs to do a better job of managing the balance between shareholders, customers, suppliers, and staff. And also managing communications with media, consumer groups, regulators, and politicians.

The future

Assuming pollical pressure can be defused, and relations with consumer groups, suppliers, and staff can be restored, the company should be able to continue to reap the rewards from its oligopoly cartel - if they can avoid doing dumb things.

In the absence of risky adventures into new overseas markets or new sectors at home, returns on equity should remain above-market, which should translate into superior growth in earnings and dividends once again.

In the short term, there is probably some upside in profit potential by improving the core business, but that is probably only short term. The current above-market pricing suggests that is already priced into the share price.

In fresh food retailing, probably a relatively small share will ever be done online. Woollies is leading in that sector, driven by the new group CEO.

As the incumbent dominant supermarket chain, if it sticks to its core business, the single biggest determinant of long-term future growth will be Australia’s high population (immigration) growth rate. Fortunately, this looks set to continue to be strong.

You decide!

This quick, initial snapshot no substitute for more detailed research required to make investment decisions. Investors, advisers, and portfolio managers should do their own research to arrive at your own conclusions.

You decide!

See also:

Disclosure: I have been a long-term shareholder in Woolworths Ltd, but readers should certainly NOT imply or assume anything from this, as my holding reflects a decision I made many years ago, and this may or may not reflect a similar decision today.

As always, my analysis is fact-based and intended to be as dispassionate as possible, regardless of whether or not I am a buyer, a seller, or holder. This quick, initial snapshot is no substitute for more detailed research.