This is the story of my adventure with Qantas shares – and proof that the ‘Bigger Fool’ theory works!

Media headlines writers are having a field day with all the recent dramas surrounding Qantas.

Outgoing Qantas CEO Alan Joyce must be the most hated CEO in Australia since Stuart Fowler (CEO of Westpac during the disastrous lending binge in the late 1980s that brought on the early 1990s ‘recession we had to have’, with 18% interest rates, 11% unemployment, widespread bankruptcies, and near-fatal banking crisis).

However, investors need to ignore the media hype, and focus instead on the company itself, to decide if they want to be a part-owner.

The numbers

The Qantas share price (despite Covid, and thanks to Joyce’s savage cost-cutting, tricky revenue-boosting strategies, and outstanding political lobbying) has beaten the overall ASX market index by a whopping 11% per year for the last decade.

That’s hard to ignore – but can it continue? Would a long-term investor want to be a part-owner?

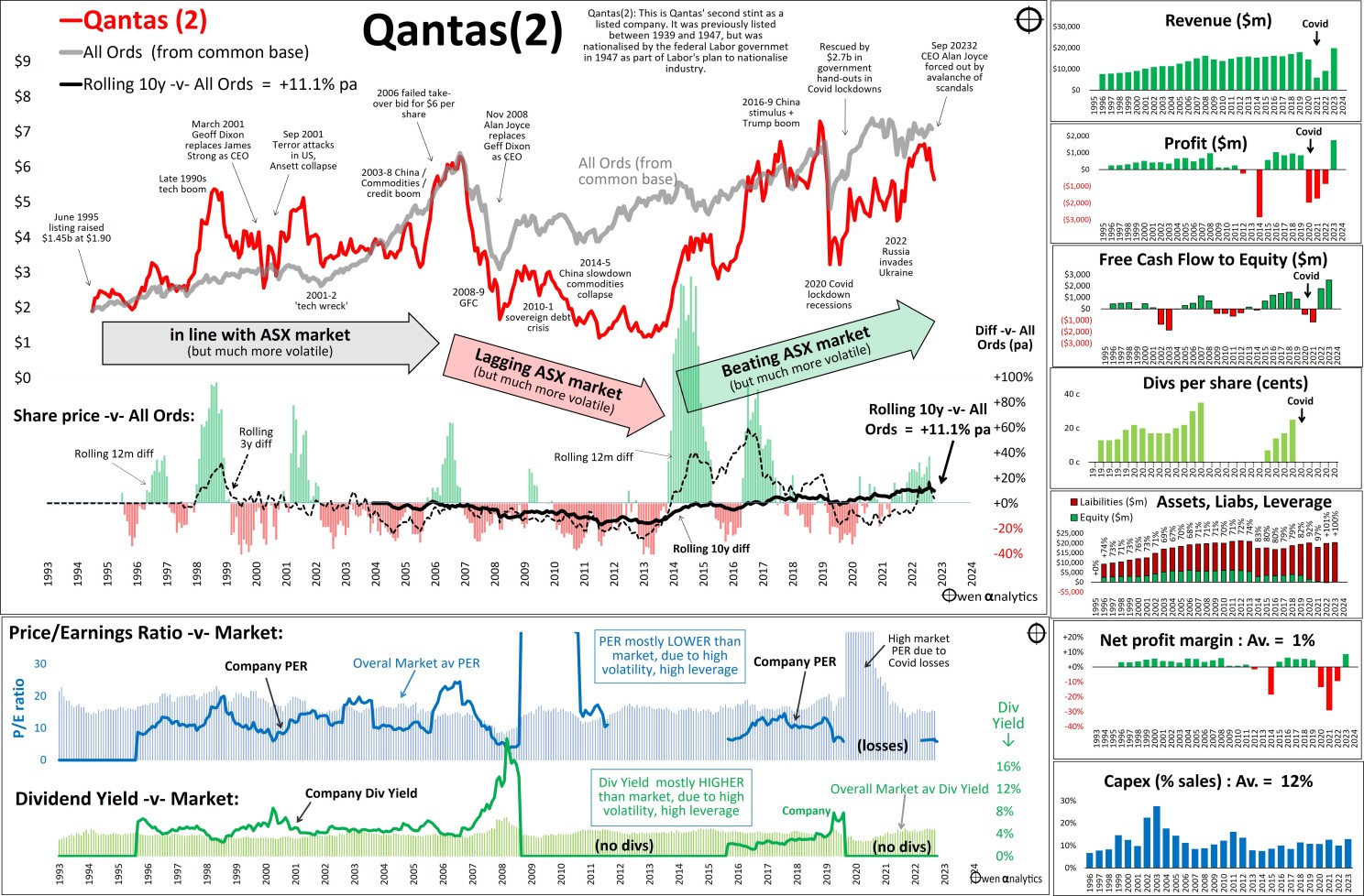

Here is my standard set of charts as the starting point for assessing a company.

Owen Analytics charts for Qantas

The main chart shows the share price (red) since the 1995 re-float, versus the overall market index (grey).

The lower section of the main chart shows the rolling 12-month difference (green/red bars), the annualised rolling 3-year difference (black dotted line), and annualised rolling 10-year difference (black line). I want to see this black 10-year line above zero most of the time.

In this case, the share price has beaten the broad ASX market by 11% per year on average for the past 10 years to August 2023: 15% pa for Qantas versus 3.9% pa for the broad ASX market.

(Note that it paid no dividends for two thirds of the past decade, so the difference in ‘total returns’ is ‘only’ 8% pa – still well above the overall market).

The smaller charts to the right are some of the key metrics – revenues, profits, etc.

The chart below the main chart shows the main valuation metrics - price/earnings ratio (blue) relative to the market average, and dividend yield (green) relative to the market.

Beyond the numbers, let’s take a look at the company itself -

Brand trashed in Australia, but still good overseas

For many decades, Qantas has been the best-known Australian brand in the world, and it was certainly one of the best-loved domestic brands within Australia.

It is the world’s third longest surviving airline (KLM is the oldest), and it has one of the best safety records (Dustan Hoffman’s Rain man was wrong: Qantas is not fatality-free as the legend goes – it did have a fatal crash in 1934).

It is one of the very few non-government airlines in the world that posts profits (occasionally anyway).

What’s not to like?

123 year history

‘QANTAS’ (short for ‘Queensland and Northern Territory Aerial Services’) began as a private company in the outback Queensland town of Winton in 1920.

Contrary to popular belief, it did not ‘IPO’ in 1995, because it was previously a listed company. It’s shares were initially listed on the stock exchange from 1939 to 1947, but in 1947 the company was nationalised by the Commonwealth government as part of Labor’s post-WW2 attempt to nationalise several industries.

Qantas was re-listed on the stock exchange in June 1995, when the government sold its 75% stake, raising $1.45 billion from the public at $1.90 per share (the other 25% was owned by British Airways).

Investment case

One of our tests for a company is that we want to see its share price beating the broad market for periods of at least ten years, because we want to see out-performance that is sustained well beyond just one business cycle, or one CEO, or one set of market conditions (competition, regulation, industry structure, etc).

Although Qantas has passed this share price test handsomely over the past decade (but it didn’t before that), we need to look further to assess what is really going on in the business, and if the share price out-performance is sustainable. (Since the second listing in 1995 it has lagged the overall index and has been much more volatile).

Qantas provides a useful lesson that even a strong share price out-performance for a decade does NOT automatically make it a good investment for the future.

Since the company’s second listing in 1995, the share price has gone through three main decade-long periods.

The First decade – sideways but extremely volatile

In the first phase, the share price ended square with the overall share market, but it was a much more volatile ride. The share price more than doubled in the late 1990s tech boom, but then fell back to be square with the market by 2004, while revenues, profits and dividends grew steadily (but not cash flows, as we shall see).

Second decade – downward spiral

During the second phase, the share price collapsed by more than two thirds to just $1 per share by 2013. In this phase, the share price lagged the market by minus -15% per year, or minus 80% in total. In 2014 it posted a $2.8b loss, after writing off $2.9b on over-valued assets.

In the middle of this phase, CEO Geoff Dixon organised a failed debt-financed takeover bid at $5.60 per share, backed by a consortium comprising Macquarie Bank (shifty investment bankers), Allco (even shiftier, and bankrupt shortly after), and TPG (shifty US private equity scoundrels).

The ridiculous bid failed to get more than 50% of shareholders to take it up because they thought the business was worth even more! (What planet were they on?). Share price promptly collapsed in the GFC and the bidders ran for cover.

The problem with Qantas was not revenues, which remained around flat. The main problem was its huge debt load, which resulted in big losses, and the end of dividends.

Third decade – beat the market – through Covid!

The third decade-long phase (2014-2023) saw the share price surge back and beat the overall market by an average of 11% per year for a decade, but still with much higher volatility.

Dividends were restored briefly from 2016 to 2019, but then the Covid lockdowns crippled travel, and dividends were abandoned once again.

Magnificent political lobbying by CEO Alan Joyce resulted in $2.7b in government handouts to prop up the so-called ‘national carrier’ (which had not actually been ‘national’ since the government sell-off in 1995).

Cashless bird

There are two main problems with the business. The first is cash flow.

In the 28 years from listing in 1995 up to 2023, the company generated a total of $51 billion in operating cashflows (ie customer revenues less operating expenses and interest costs). Of this, it spent $43b (ie 85% of cash flows) on capital expenditure (‘capex’), leaving only $8b (or 2% of revenues) in free cashflows.

That is extraordinarily skinny, especially when revenues (ticket sales) are so cyclical, and the main cost (jet fuel) is so volatile.

The company paid out generous dividends to shareholders (at least in the early years), and extraordinarily generous salaries and bonuses to executives (even in the loss years). Since listing in 1995, total dividends paid out have exceeded total profits by 50%. (Borrowing to pay dividends - the Telstra disease!).

As a result, shareholders’ funds have been run down to zero (in 2022 it was negative, and in 2023 it was $10m, which is basically a rounding error).

The balance sheet value of the company is zero, and that doesn’t include a host of off-balance sheet liabilities and contingent liabilities.

Debt

How do you keep a business running despite generating virtually no cash? Easy – just load up on debt! (And endless lobbying for free government hand-outs and favours.)

The fifth chart on the right shows the gearing ratio starting from a rather high 74% of assets in the mid-1990s, then increasing to 100% by 2022. (Most companies run gearing ratios of between 40% and 60% of assets).

In the past 20 years, debt (maroon bars) has doubled from $10b to $20b, but shareholders’ funds (green bars) have disappeared entirely. The business has zero net asset value because every dollar of assets is financed by a dollar of debt.

The company is basically a highly geared, government-protected, virtual monopoly that survives on government hand-outs, subsidies, protection, and political favours. Governments keep it alive mainly for the ‘feel-good’ factor of having a locally owned ‘national carrier’ with a globally recognized brand that is key part of Australia’s tourist marketing campaign.

(NB. The current Albanese government no longer wants tourists – in August 2023 it rejected an additional 28 planeloads per week of cashed-up tourists from Europe – to protect Qantas’ price gouging!)

The business is highly capital intensive, it’s top-line revenue stream is very cyclical and vulnerable to cyclical swings and sudden disruptions, and its main non-staff cost item (jet fuel) is extremely volatile and completely outside the company’s control. It is probably the single dirtiest fossil fuel burner in the country.

People

Despite all of these problems, even the toughest business conditions can be conquered with the right people. Unfortunately, the lack of discipline from real competition, and the assurance of ongoing government support, is not conducive to tough and inspired management.

Have the CEOs and Chairpersons been up to the job?

CEOs

The CEOs have been mostly competent – James Strong 1993-2001 (career lawyer, plus Australian Airlines CEO 1983-9), Geoff Dixon 2001-8 (who’s attention was diverted trying to line his pockets big-time by leading the ridiculous failed $11b take-over bid in 2006).

The most recent CEO since 2008 was Alan Joyce (ex-Jetstar, Ansett, Aer Lingus). He juggled lining his pockets from the $2.7 billion in government Covid hand-outs and subsidies, while cutting thousands of jobs, outsourcing thousands more to low-wage countries and low-wage suppliers and collecting revenue from selling thousands of tickets on non-existent flights.

(Note to next CEO: learn from AMP and sell tickets on non-existent flights to dead people. Dead people can't use the tickets and they can’t complain!)

In the midst of all of this, somehow most Qantas passengers arrive more or less on the right day, in more or less the right destination, with more or less most of their luggage turning up in more or less in the same place. Success!

After the Alan Joyce circus, the new CEO Vanessa Hudson seems like a competent accountant - ex-Deloitte (hold your nose when you say ‘Deloitte’) – but she is untested as a CEO. Who knows?

Chairperson’s lounge

CEOs come and go, but the buck stops with the Chairperson, and these has been ordinary as well.

Qantas got off to a good start with Gary Pemberton 1993-2000, with deep experience in the international transport industry (ex-Brambles, where he successfully built Brambles into a global business as CEO 1983-93, then Brambles Chairman 1993-6).

However, since then, the Qantas Chair has been wanting sorely in relevant experience - Margaret Jackson 2000-7 (competent career accountant with KPMG), then Leigh Clifford 2007-2018 (mining career with RIO, including CEO 2000-7). The closest they got to the airline industry was sitting on shareholder-funded flights, and no doubt swanning around the Chairman’s lounge.

The current Chair since 2018 has been Richard Goyder, ex-CEO of Wesfarmers 2005-2017, where he presided over two monumental wealth-destroyers – the Coles acquisition, and the failed Bunnings UK experiment. During his reign, Wesfarmers share price went nowhere, dividends fell, and return on equity collapsed from 20%+ to single digits. Hardly confidence-building.

What is it worth?

Is Qantas a good buy today?

It’s cheap, and it should be. The charts along the bottom show that its price/earnings ratio (when it made profits) has always been lower (ie cheaper) than the overall market, because of its problems.

Its dividend yield (when it paid dividends) has always been higher (ie cheaper) than the market.

The extreme share price volatility means there is the potential to make short-term profits (and losses) trying to ride the swings, but is it cheap enough and good enough for me to want to be a part-owner for the long haul?

In 2006, the then CEO Geoff Dixon and his private equity cowboy mates thought it was worth $11b, but they were nowhere to be seen when the ‘market value’ dropped to just $2b three years later in 2009. ‘Value’ is fickle.

The ‘market value’ of the business is now back up to just $9b today, based on the current share price. But it has zero equity value on balance sheet, and that’s before off-balance sheet liabilities, contingent liabilities, and regulators are lining up to sue it for a host of reasons.

It generates virtually no net cashflows after capex, and its return on equity has averaged just 1% since 1995. Total profits of $5b (including government hand-outs) on total revenues of $365b since 1995.

Bigger fool

I bought Qantas shares in the early 2000s for some unknown reason. I was always looking for a chance to get rid of them, but the share price hovered around $3 or so between 2000 and 2005.

There is an old saying in the markets: if a fool pays too much for something, there is always a ‘bigger fool’ out there somewhere who will pay an even higher price for it. You just need to find a bigger fool!

Fortunately, a bigger fool did come along! The crazy take-over bid run by CEO Geoff Dixon and his band of shifty bankers with bucket-loads of debt, at a crazy price at the top of the pre-GFC credit boom!

The bigger fool theory worked!

Since then, I have learned to take a much deeper look into a company’s operations, management, and prospects before buying!

You decide!

This is just my view of the historical facts as I see them. It is certainly not ‘advice’ or recommendation to buy, hold, or sell.

As always, every investor must do their own research and make their own decision!

Please let me know your thoughts. .