CSL has been a favorite for investors in Australia for three decades – for good reason:

- It is one of Australia’s very few home-grown global success stories, with more than 90% foreign-sourced revenue.

- It has created more shareholder wealth than any other company in the past three decades: $115b in capital growth plus $11b in dividends.

- It has beaten the broad market index by an average of 15% per year since listing in 1994.

- In the 29 years since listing, it has posted a profit every year, increased dividends in 25 out of 29 years, and has never reduced or cut dividends.

- It is one of only ten companies to have once claimed the title of largest company by market value on Australian stock exchanges in the past 170 years (it has is now the third largest).

As a result of this phenomenal performance, CSL has always been expensive. It is on many investors’ ‘to buy’ list – at the right price.

But at what price is it worth buying? For the past few years, I have heard many people say: ‘When it dips below $300 per share'. It hit $340 in early 2020 but has been below $300 ever since, and is now down to $240.

‘Buy the dip?’

Great companies are almost always expensive, so patient investors usually have to wait for a time to ‘buy the dip’, when prices fall in a general market sell-off.

(Long-term investors love market crashes and panics – they provide rare opportunities to buy their target companies at good prices).

CSL’s share price has been in a big ‘dip’ since May 2023, but it keeps on dipping lower.

Does this mean it is finally becoming cheap enough to buy? Or has something changed?

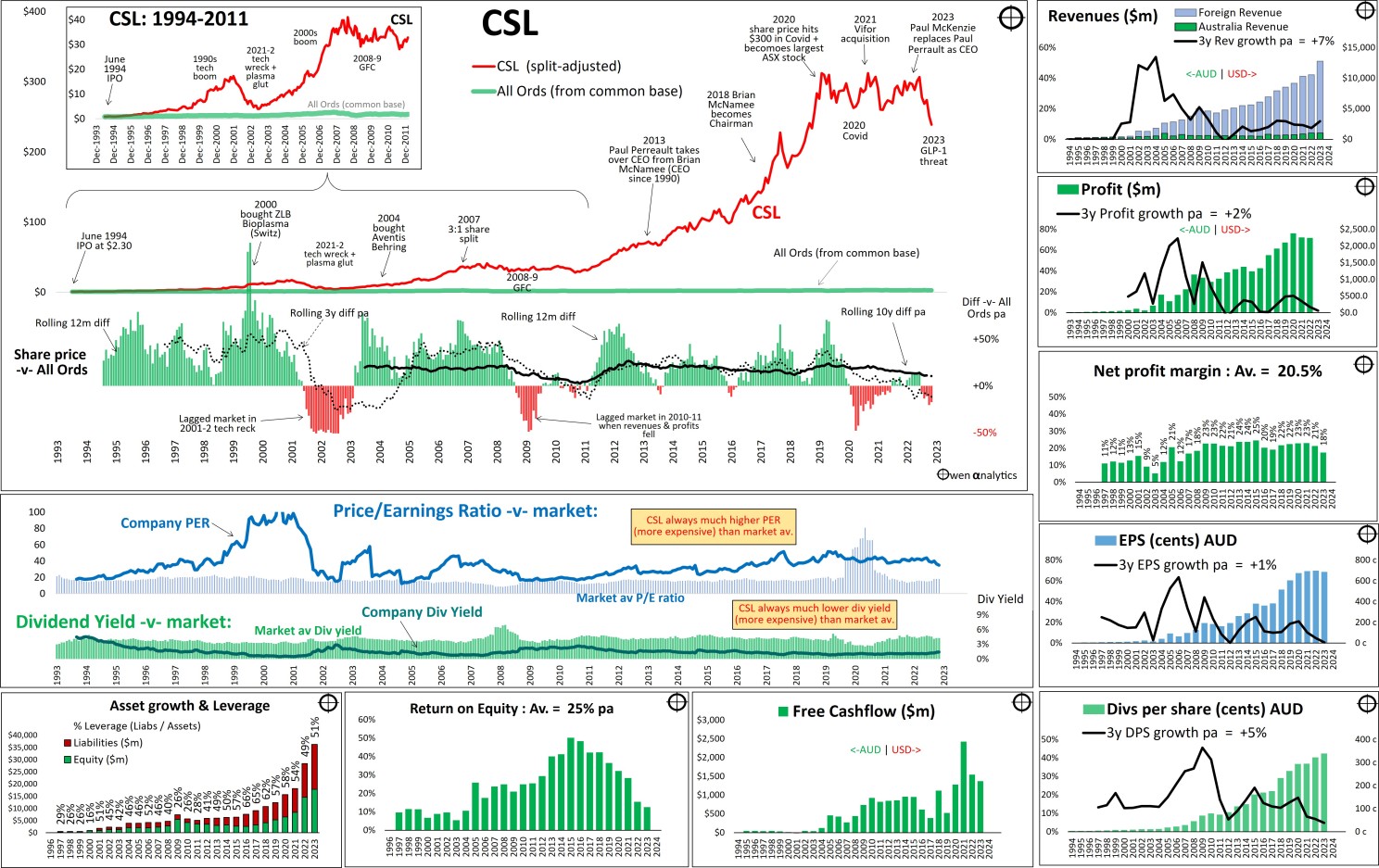

The charts

These charts are my standard starting point for assessing a company. The main chart shows the share price (red) since the 1994 float, versus the overall market index (green). In this case, the ‘All Ords’ appears to be virtually flat along the bottom, which it has been, compared to the explosive growth of CSL.

CSL charts owen analytics

The lower section of the main chart shows the share price performance relative to the market index on three timeframes:

- The rolling 12-month difference (green/red bars) - this has mostly been positive, but there have been some negative (red) periods when the share price has lagged the overall market on several occasions.

- The annualized rolling 3-year difference (black dotted line) - this is currently underwater, as the share price has lagged the market badly since peaking in early 2020.

- The annualized rolling 10-year difference (black line) - the black 10-year return has always been above zero on a rolling 10-year basis, despite shorter-term volatility.

Pricing

The chart below the main chart shows the main valuation metrics – price/earnings ratio (blue) relative to the market average, and dividend yield (green) relative to the market.

These show that the company has always traded at a higher price/earnings ratio (more expensive relative to profits) than the overall market, and the dividend yield has always been lower (more expensive relative to dividends) than the overall market.

This is natural for a high-growth company that is growing profits and dividends at faster rates than the overall market.

The smaller charts to the right and below the main charts show some of the key metrics – revenues, profits, margins, cash flows, return on equity, gearing, etc.

Rare global success story

CSL was one of the smaller 1990s government privatizations, but it was the only one to turn into a global giant.

Its market value grew from $300m at its float in 1994 to $145b in 2020 when it briefly overtook CBA and BHP to become the most valuable company on the ASX in the depths of the 2020 Covid lockdown crisis.

Its share price rose 400-fold from $2.30 at float (77 cents in split-adjusted terms after a 3:1 split in 2007) to $340 per share in February 2020.

It is a rare global success story on the ASX, with more than 90% of revenues and profits coming from highly competitive offshore markets.

All of that was achieved as an ASX listed company since 1994, under the guidance of one person – CEO and now Chairman, Brian McNamee. He has certainly been one of Australia's greatest business heroes.

Sleepy government department

Although it is a global success now, for the first 75 years of its life, ‘Commonwealth Serum Laboratories’ was a sleepy government department formed in 1916 as a local manufacturer of anti-venoms and vaccines for humans and animals when import supplies were cut off in WW1.

By the 1990s, CSL had two main businesses as a government department. First, it charged the government a fee to process blood collected from blood donors into the Red Cross Blood Bank. It used the blood to make three main types of products:

- pro-coagulants (for hemophiliacs);

- immunoglobulins (for enhancing immune systems), and

- plasma volume expanders (for burn victims and blood transfusions).

CSL had a local monopoly on this blood ‘fractionation’ process, but its survival was entirely at the discretion of the government; and volumes depended on the level of Red Cross blood donations.

CSL’s other main business was manufacturing foreign drugs locally under license from global pharmaceutical giants. That business was also a locally protected monopoly that relied on the government continuing to ban foreign drug companies from selling direct into Australia.

Pre-float problems

Although CSL was posting accounting profits before the float, it had negative cash flows for many years because of spending on R&D and plant & equipment. It was not an attractive proposition for investors.

To make matters worse, CSL was fighting off lawsuits over contaminations that had allegedly caused the spread of HIV/AIDS and other complications from its blood products.

To sweeten the float, the government granted the company immunity from these legal claims, and also locked in the government plasma fractionation contract for 10 years.

It was a protected monopoly with a bag of problems.

Float shunned by locals

The float was largely shunned by local investors and share funds, but it did attract more interest from foreign investors. In the IPO, the Commonwealth government raised $299m by selling 130 million shares to the public at $2.30 per share (77 cents split-adjusted, in today’s terms).

It turned out to be a tremendous success right from the start, mainly for the foreign investors who saw the potential.

September 11 terror attacks

CSL’s tremendous growth has not been without problems. In the early 2000s, there was a global plasma glut following the 11 September 2001 terrorist attacks on New York and Washington. This crippled revenues and profits for several years.

Another problem was subsequent government moves toward allowing foreign drug companies into Australia, which undercut CSL’s cozy protected monopoly.

Covid border closures

CSL was also affected by US President Trump closing the border to Mexico, cutting off the supply of blood donations from illegal Mexicans in CSL’s collection centers along the border. (CSL essentially buys blood cheaply from poor Mexicans at the border and makes it into expensive blood products it sells to rich Americans.)

Despite these setbacks, the company prospered, due to two key factors: strategy and people.

Success factor 1: Strategy

The ASX is littered with failed attempts by local Aussie companies trying to take on the world by competing head-on in foreign markets against foreign incumbents with deep experience on their home turf, and/or overpaying for acquisitions they don’t understand, in markets they don’t understand.

CSL was smarter. It focused on plasma, which was shunned by ‘big pharma’ giants as unprofitable, problematic, diversions from their core businesses. Big pharma was keen to get rid of their plasma operations, and CSL bought well.

Also, unlike many failed Aussie overseas adventures, CSL started out small and took many years to do its homework on its foreign acquisitions and expansion plans.

Small acquisitions started in 1994, but the big ones were:

- ZLB Bioplasma (Switz ‘Red Cross’ blood plasma business) in 2000 for $930m, which doubled CSL’s size.

- Aventis Behring (US) in 2004 for $956m.

- Vifor (Swiss-based renal therapy and iron deficiency, with mostly US revenues) in 2022 for US$11.7b.

Success factor 2: People

The second main ingredient was the key people, actually one in particular. In 1990, the government woke up the sleepy department by hiring 33-year-old Brian McNamee from the local company Faulding to be CSL’s new CEO.

It turned out to be an extraordinary hire.

McNamee ran the company for 23 years until 2013 when he handed over the reins to American Paul Perreault, who came via the Aventis Behring acquisition in 2004. Perreault continued the careful growth path, doubled CSL’s revenues, lifted earnings per share by 160%, dividends per share by 190%, and trebled the share price.

Meanwhile, former CEO Brian McNamee returned as chairman from 2018 (after a suitable break to prevent any CEO-to-Chairman problems that many boards suffer).

New outsider CEO in 2023

Perreault retired after 10 years as CEO, and McNamee hired American Paul McKenzie as the new CEO from March 2023. One positive has been that McNamee (and the later CEOs) have been salaried technicians, not flashy ego-driven founder/owners. The new CEO is an outsider and untested, but McNamee still in the Chair provides a degree of comfort.

GDP-1 ‘disrupter’?

One new factor in the equation is the possible negative impacts of the new diabetes/weight-loss wonder-drug ‘GLP-1’ (glucagon-like peptide 1). If GLP-1 drugs become as widespread as many fear (or hope), especially if they are available in pill form rather than injections, it may result in fundamental changes to many industries, not just diabetes and weight loss, but other industries like junk food, soft drinks, clothing, exercise equipment, gyms, insurance, and perhaps others.

However, like all so-called ‘disrupters’, the impacts of GLP-1 drugs will probably turn out to be very different from the initial hype. But who knows?

Accounting trickery

This is another unwelcome development. CSL has always prided itself on very simple accounts, with no accounting trickery. That is no longer the case. When the going gets tough, CSL has resorted to a few little tricks to dress up the accounts so they appear better than they actually are.

Space prevents me from detailing them here, but readers can use this as a case study on some common techniques to tart up the numbers in the latest full-year accounts.

This is a black mark for McNamee. He should know better, but he is probably under enormous pressure from his newly hired CEO wanting to look good and get rich.

Perennially pricy

The main problem is pricing.

When it was a high-growth company, it was always very expensive. It was always on investors’ ‘to buy’ lists, just waiting for the chance to ‘buy the dip’.

But when is it cheap enough to buy? Often the response is: ‘When it dips below $300 per share' - which it hit in early 2020 and then went more or less sideways.

The problem is that $300 per share is 50 times earnings, and 100 times dividends (i.e., a dividend yield of just 1%).

Even at $240, that is still 35 times earnings and 60 times dividends (1.4% dividend yield).

Those high multiples might be fine for a company with consistent double-digit growth in revenues, earnings per share, and dividends, but that was CSL in the 1990s and 2000s growth era, not today.

Single-digit growth

In recent years, growth rates for revenues, earnings, and dividends have been running at only single-digit growth rates. That would only justify earnings multiples and dividend yields not much above the rest of the market – i.e., less than 20 times earnings, and a dividend yield of at least 3% or 4%. Return on capital and return on equity have also been declining for several years.

High multiples would only make sense if we could be assured the company will magically return to double-digit growth in revenues, earnings, and dividends – and continue that way for the next decade at least.

You decide!

Can the new CEO, guided by the experienced Chair McNamarra, manage to overcome the current obstacles and return the company to its former glory days of double-digit growth in revenues, earnings, and dividends?

(If growth rates in the next 30 years were just half of what they were in the past 30 years, it would make CSL the largest company in the world, overtaking Apple and Microsoft.)

Or has it become just another mature, low-growth stalwart reliant on repeated acquisitions for growth?

This is just my view of the facts as I see them. It is certainly NOT ‘advice’ or a recommendation to buy, hold, or sell. My aim is to provide dispassionate information, insights, and informed analysis for portfolio managers and advisers.

As always, every investor must do their own research, seek professional advice, and make their own decision.

‘Till next time – happy investing!