Our largest export customer and greatest source of wealth & prosperity – is also our greatest potential military threat - is this a problem?

- The answer is no, but for reasons you may not expect.

- Here is why I am bullish on Australia’s continued resource-based prosperity as global tensions escalate.

- Australians have been masters at turning geopolitical shifts and crises into economic advantage!

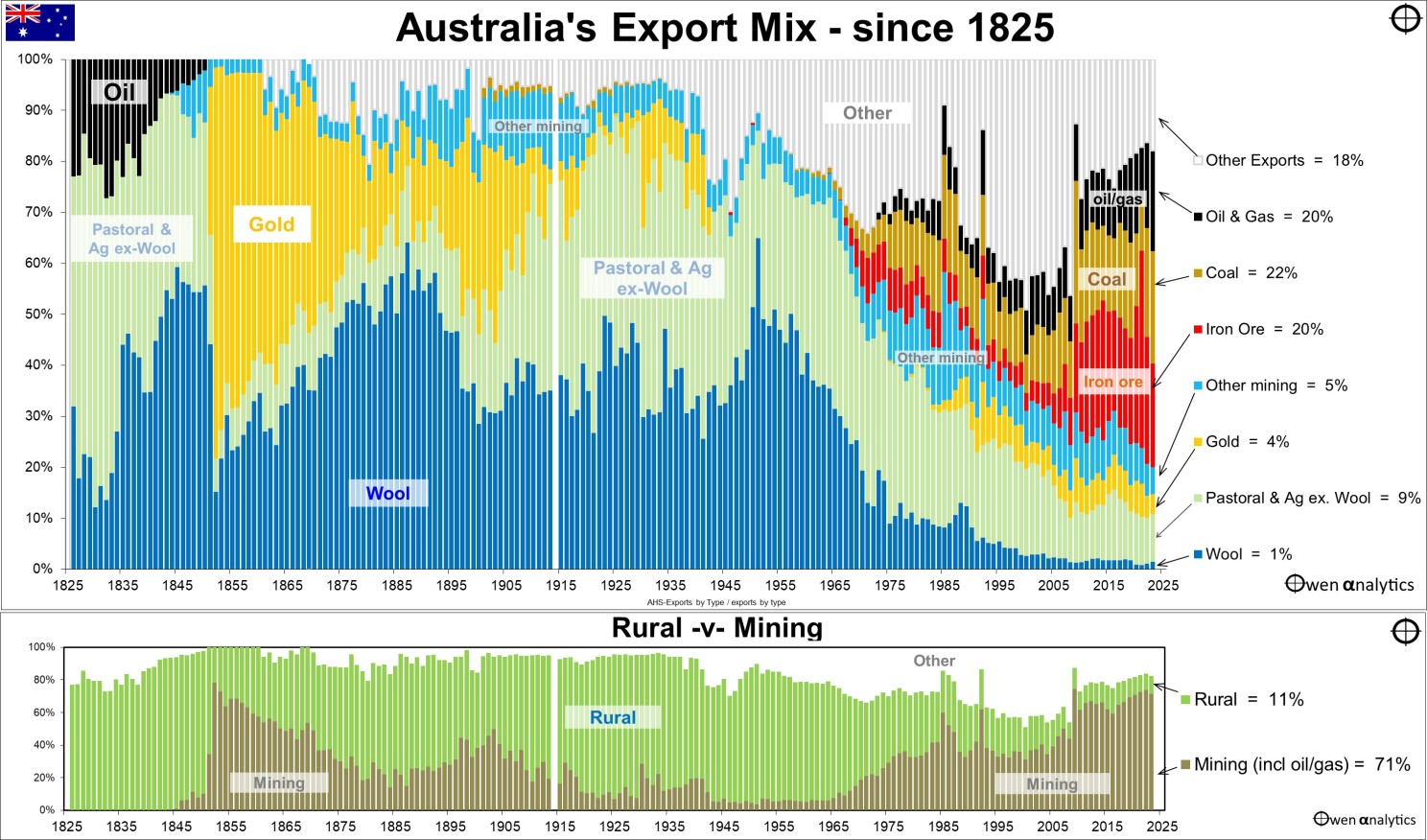

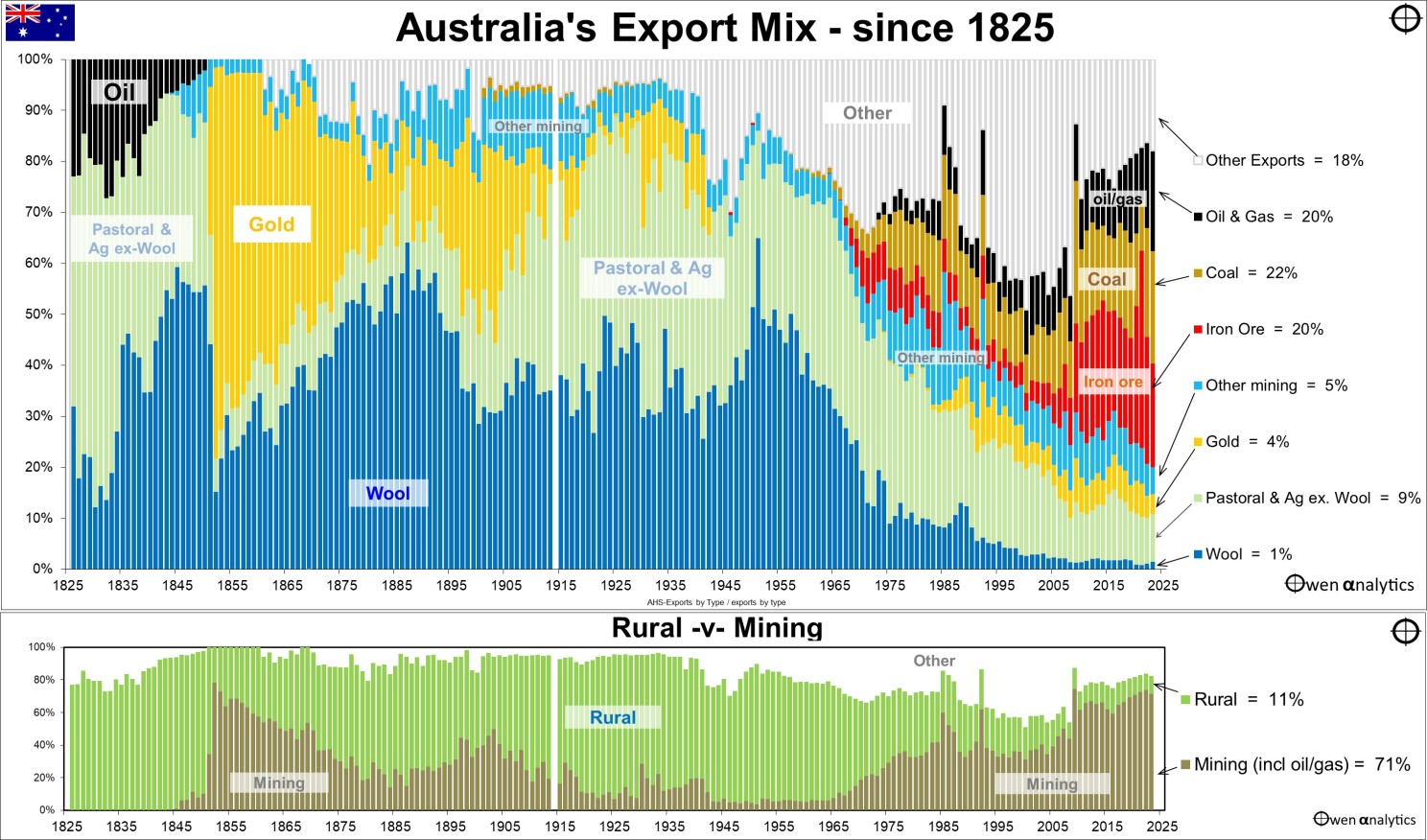

In a recent story I highlighted Australia’s diversity and flexibility in its types of resource exports -

Australia's bounty: 400 years of exports. Is it just 'luck'? Or masterful ability to adapt and pivot? (15 Nov 2023)

Today's edition tells the equally remarkable story of the changing mix of Australia’s exports by destination – prospering from global shifts in economic and military power. Australians have been masters at turning geopolitical shifts and crises into economic advantage!

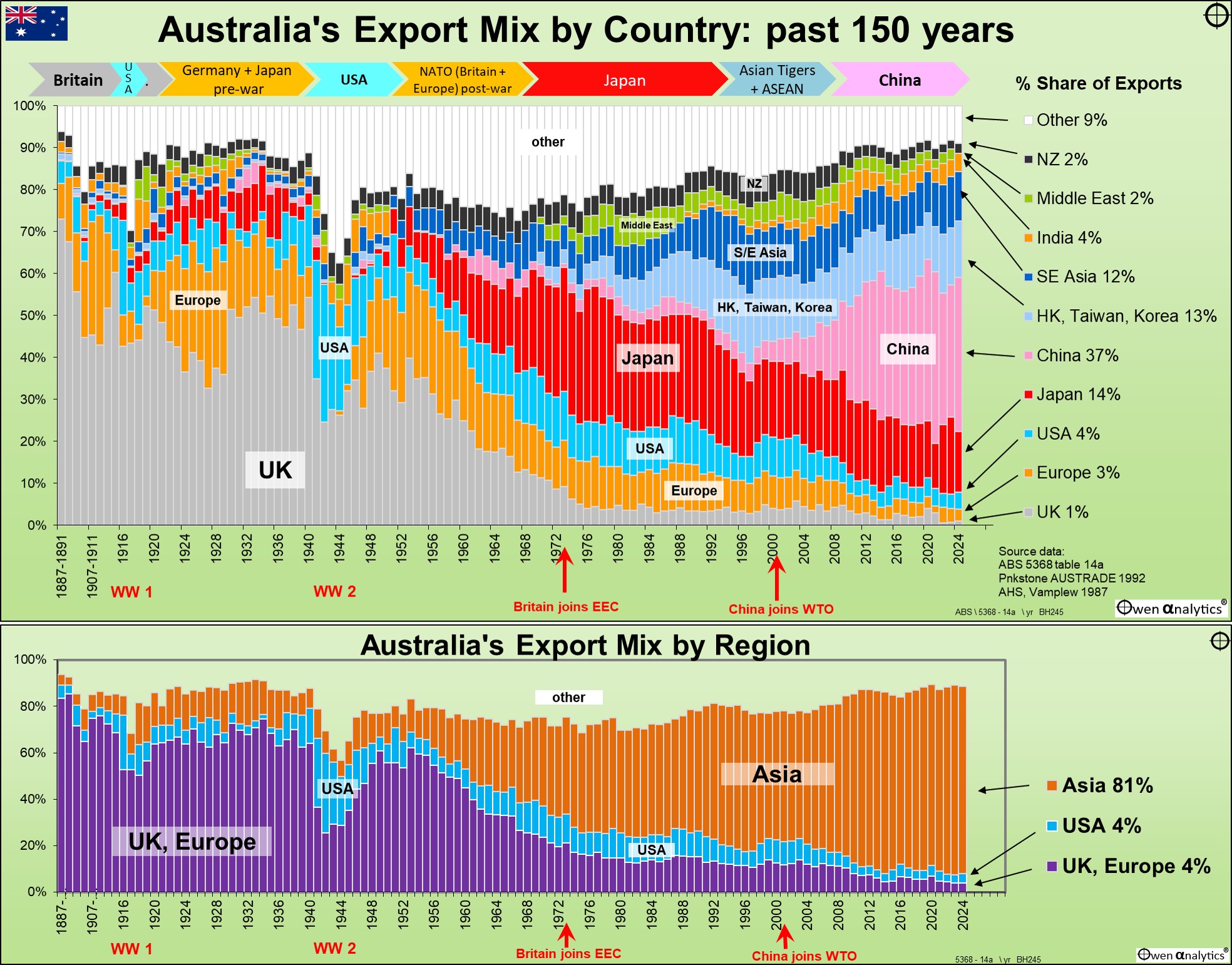

Australia’s changing mix of exports by destination

Today’s chart shows the changing mix of Australia’s exports by destination over the past 150 years.

It is essentially a chart of global shifts in power and engines of economic growth over the past couple of centuries - from Britain and Europe, to the US, and then to Asia.

One of the great stories told by this chart is how Australia’s raw materials exports played a central role in helping build industrial and economic capacity across the world – firstly in Britain, then Europe, and then in a string of Asian nations as they ‘emerged’ or (re-emerged) one by one after WW2.

First Japan, as a US ally after WW2, then the Asian Tigers (Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan), then ASEAN (including Malaysia, Thailand, Philippines, and Indonesia), and now China.

Each emerging industrial powerhouse was built largely with Australia’s resource exports.

Australia’s heavy reliance on China for our wealth and prosperity

China is Australia’s largest export customer by far. Booming exports to China have been the single largest contributor to our national revenues, wealth, and living standards this century. Australia has not been as reliant on a single country for our export (and tax) revenues since 1953, when our largest export buyer was ‘Mother’ England.

China has used its imports of Australian iron ore, coal, and a host of other metals and raw materials to build not only vast new cities, factories, ports, freeway systems, and rail networks, but also new military bases, war ships, aircraft, and bombs that one day may be used against us.

Is China a threat? Militarily, probably not (ie not likely to physically invade, subsume, or plunder Australia directly), but economically, perhaps.

After anointing himself Emperor for Life, Xi Jinping is building a network of dependent client states across the Pacific, through Central Asia to Europe and Africa, and pursuing territorial expansion in Asia, including building military bases in disputed waters in the South China Sea, subsuming Hong Kong, and stepping up his plans to invade (or ‘re-unite’) Taiwan.

Xi's vision for China is much broader that that of Mao and Deng, which was to restore China's dignity and international respect after two centuries of plunder, domination, and economic impoverishment by foreign powers. That goal has certainly been achieved as a result of Deng's reforms. Now it appears Xi's vision goes far beyond that - to territorial expansion and regional (but probably not global) military and economic domination.

Although Xi's plans probably do not include physically invading Australia, there are economic risks.

Hypothetically, in the event of a war (eg China-US over Taiwan), if Australia were still a US ally at the time, our exports to China would cease immediately. In practice, China would probably move to act much earlier and cut imports from Australia to weaken our resolve and test our allegiance with the US.

Seen it before

It may seem scary and precarious to be reliant on export revenues from a potential future enemy, but this has actually happened to Australia before - twice - in both of the World Wars of the twentieth century.

Let’s take a look at how it happened and how we got out of it and continued to prosper. First, some background:

Our wool fuelled Britain’s industrial revolution

From 1788, post-settlement Australia started out as a far-flung collection of British prison colonies supplying oil (from whales and seals), wool, grains, food, gold and other metals to Britain as part of the British trade block, protected by the British Navy. (For the century prior to today’s chart, exports were almost entirely to Britain, as our colonial master had banned trade with other countries).

During the Napoleonic Wars, Britain had switched from breeding sheep for wool for clothing, to breeding for meat (mutton). As a result of this switch, after the Wars ended, Britain needed a new source of wool to compete with cheaper Spanish and German wool, to feed Britain’s new mechanized, mass-production textiles industry. Australian wool filled the gap, effectively providing the raw material for the first key stage of Britain’s industrial revolution.

Wool was Australia’s largest export earner for almost the whole of the next 130 years from the 1830s to the 1960’s. Wheat and other grains also played a major role, along with gold in the three gold rushes (1850s, 1890s, and 1930s).

Pre-WW1 military build-up and war

After Federation, Australia rapidly increased its exports to Germany (mainly lead and zinc from the Broken Hill mines), helping build Germany’s industrial and war machine in its build-up to WW1.

When War broke out, our exports to Germany ceased and the US took over. Uncle Sam also reluctantly entered the War and won it for the allies.

Pre-WW2 military build-up and war

In the post-WW1 reconstruction, Australia again increased its exports to Germany and Italy, and also Japan (the three Axis powers), contributing to their industrial and military build-ups to WW2.

Exports to Germany and Italy were mainly base metals, and to Japan it was mainly ‘pig-iron’. (Pig iron is the around 90% iron content, made from raw iron ore, which is generally round 50-60% iron. (These days we don’t even bother to do the first stage processing at all – we just export the raw iron ore as rocks and dirt).

Trade unions here were concerned about Australia supplying iron to Japan to build war machinery for its brutal invasion of China, and potential aggression against Australia. Under union pressure, the Joe Lyons government (United Australia Party, forerunner to the Liberal Party) banned iron ore exports to Japan on 6 May 1937, and unions shut down BHP’s steelworks where the pig iron was produced.

BHP ignored the government’s ban, broke through the union blockades, and kept shipping iron to Japan anyway, to feed its hungry war machine - with the full support of Attorney General (and future PM) Bob Menzies (Menzies’ father worked for BHP).

Australia kept exporting BHP’s pig iron to Japan (with Menzies championing BHP and Japan’s cause) until the end of 1940! (That is how Bob Menzies got the nickname ‘pig-iron Bob’).

Japan did indeed continue its military rampage all the way down through southeast Asia to our doorstep. Japan’s warplanes dropped more bombs on Darwin and the north of Australia than it did on Pearl Harbour, and Japanese mini-subs even torpedoed ships in Sydney Harbour in 1942. All with arms and ammunition made (partly) with our iron exports.

Once again, when WW2 broke out in Europe and then in the Pacific, our exports to the enemies ceased and America again reluctantly came to the allies’ rescue and won the war – against Germany in Europe and against Japan in the Pacific. The US again filled the gap in taking Australia’s exports.

Likewise in the Korean War, when the US once again stepped in to buy up our exports, especially our wool. Australia’s windfall export revenues during the Korean War pushed CPI inflation up to 25% in 1951!

Post-WW2 reconstruction

In the 1950s and 1960s, Australian exports boomed in the reconstruction of Western Europe, as a US ally against communist USSR. Meanwhile, in the Pacific, Australian iron ore, coal and metals helped re-build Japan as a US ally against Communist China following Mao’s revolution in 1949.

Australia retained its ban on iron or exports but finally lifted the ban in 1960, to allow the first exports from the Pilbara to Japan, the former wartime enemy. This kicked off Australia’s tremendous post-war minerals exports boom. Japan overtook Britain as our largest customer in 1967. China, in turn, overtook Japan as our largest export buyer in 2010.

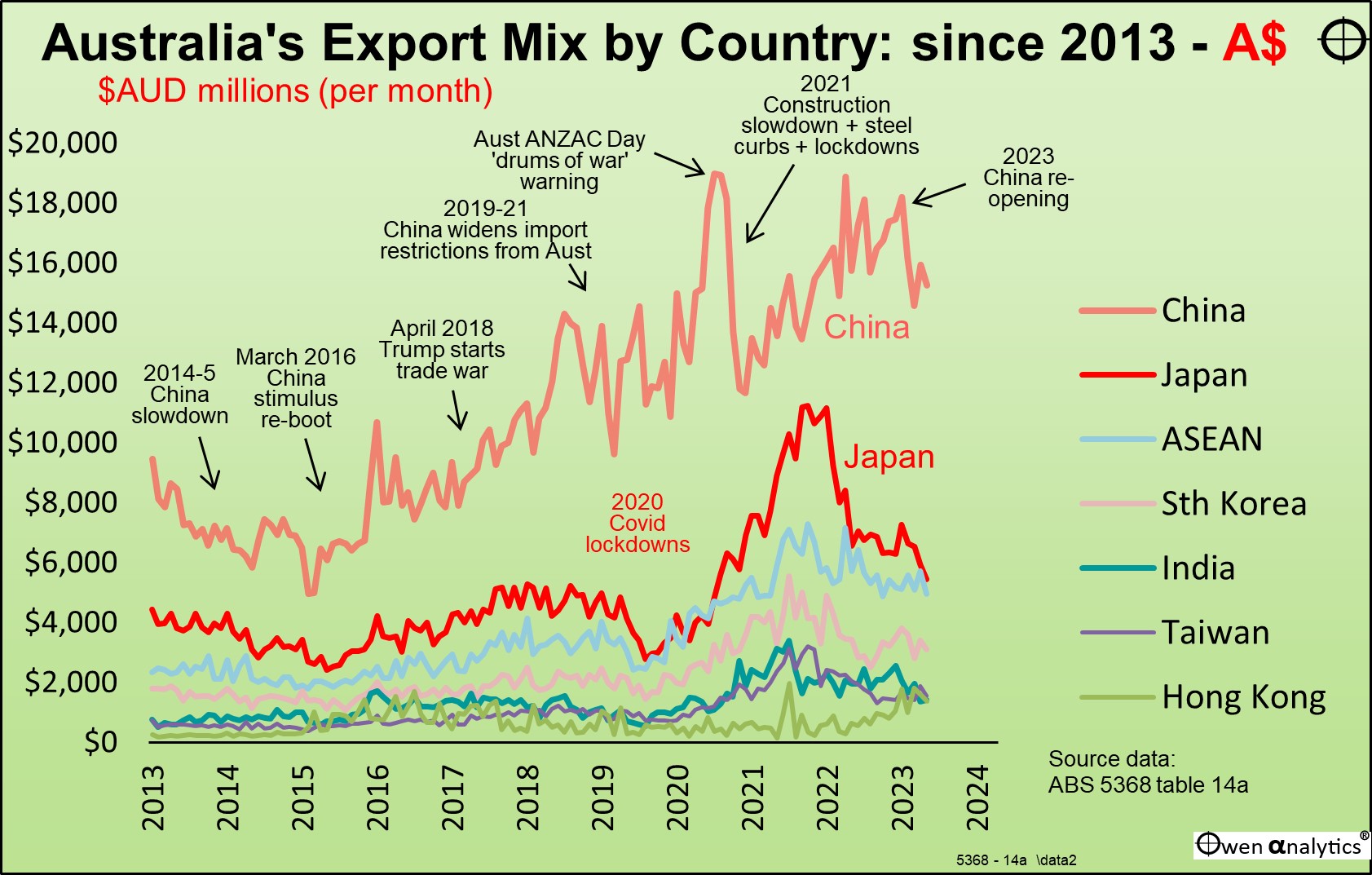

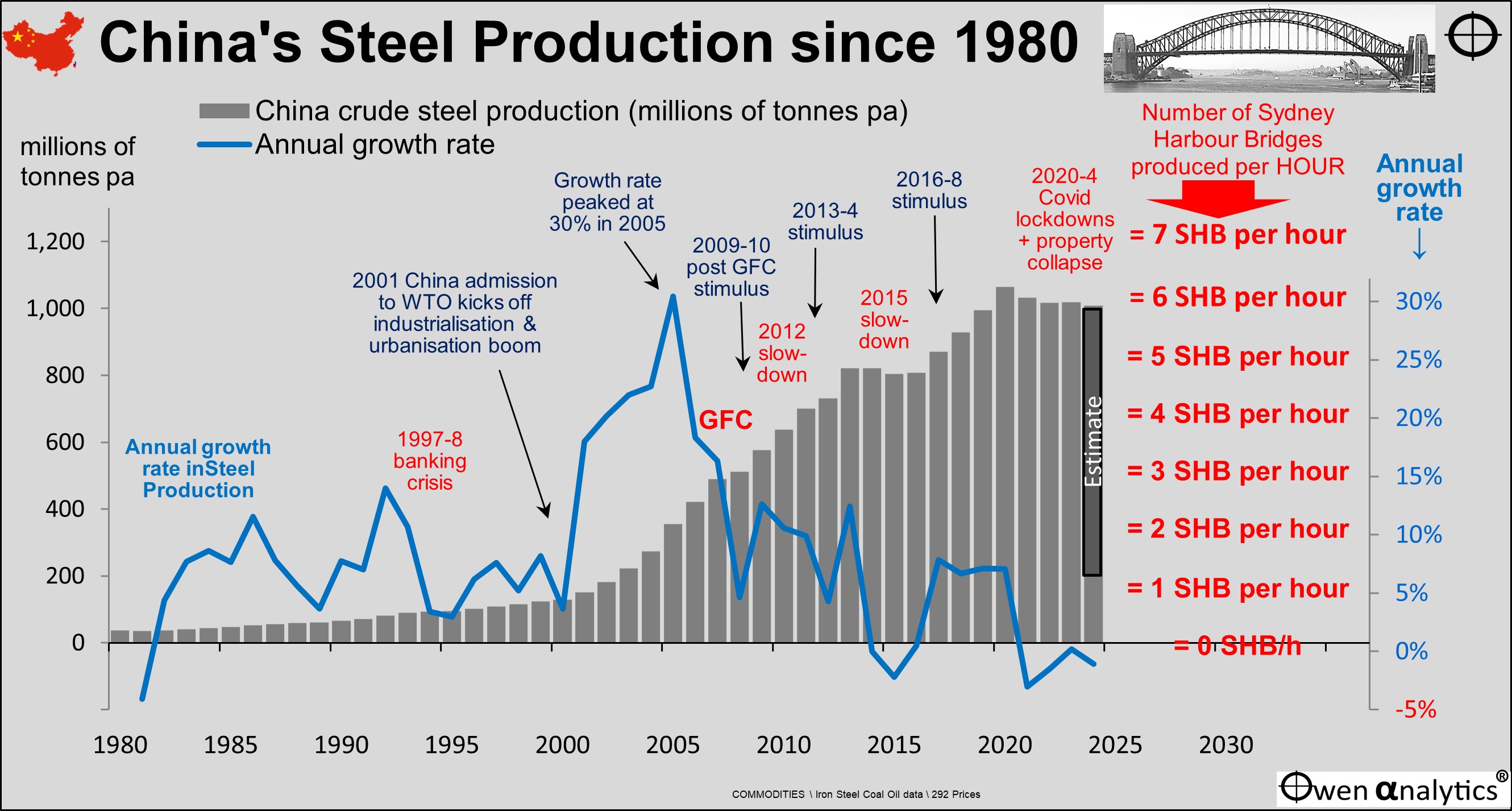

Before 2000, China bought just 5% of our exports. But China’s acceptance into the World Trade Organisation in 2001 kick-started its manufacturing export and urbanisation booms. China rapidly became our largest buyer by a country mile, and remained the largest buyer despite China’s various bans and restrictions on imports from Australia during the tariff wars started in 2018 by Trump/Morrison.

The tariff war with China was actually a blessing in disguise, as it highlighted the heavy reliance on China for many exporting companies, and forced them to develop other export markets.

Uncle Sam to the rescue

In Australia, we may not think of the US as an important export customer, but the chart shows that the US played a critical role, especially when it mattered most, in times of war when shipping lanes to other markets were cut off.

The light blue areas on the chart (exports to the US) highlight how the US came to the rescue several times – taking over when our exports to Europe were cut in WW1, again in WW2, then in the Korean War, and again through the reconstruction of Europe in the 1950s and 1960s.

Will the US once again step in as our protector and benefactor in the event of rising conflict with China?

(Does Trump even know where Australia is on a map? Can Biden stay awake long enough for a briefing?)

China needs us more than we need China

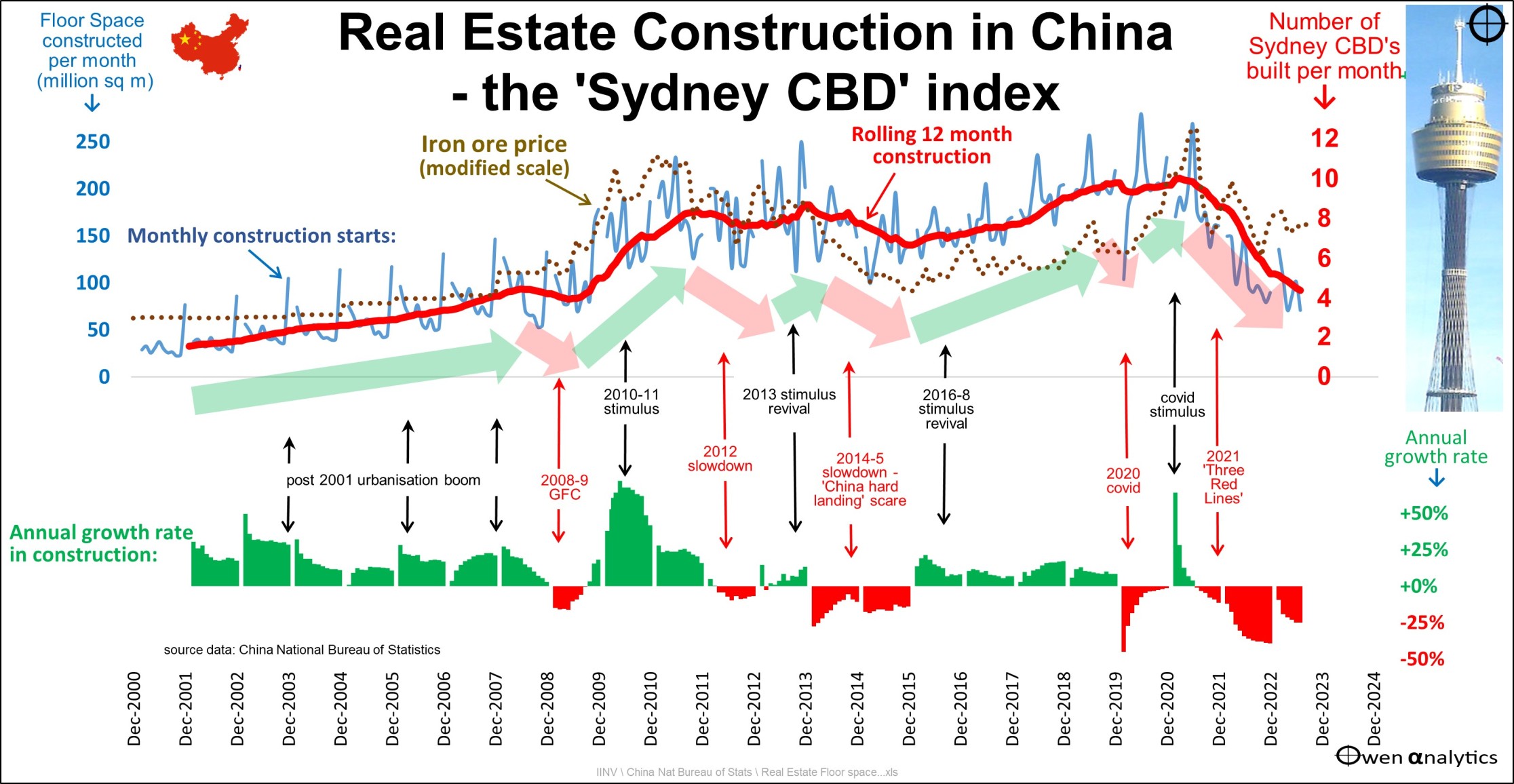

For more than two decades, China’s number one policy lever for controlling domestic economic activity has been construction, which is reliant on access to high quality, low cost iron ore and coking coal and a range of metals. China has been trying to diversify its import sources away from Australia for several years. It has been trying to find and develop cheaper sources across the world including Africa, but it simply has no choice but to buy from Australia for quality, volume, price, proximity, and political stability.

In the Covid lockdowns, Australia overtook Brazil to become the world’s largest iron ore exporter, and we also overtook South Africa to become the world’s largest coal exporter – both primarily to China.

Tariff wars have consequences - China’s ban on Australia’s thermal coal raised domestic electricity prices in China, and also led to power cuts and factory closures in a nation-wide energy crisis across China. China had to increase imports of Australian LNG (overtaking Japan as our largest LNG buyer), and started buying Australian thermal coal again to ease its power crisis.

The outcome? China needs Australia even more than Australia needs China. For China, as with Australia, domestic imperatives trump geo-politics.

De-risking and diversifying away from China

China’s share of Australia’s exports peaked at 42% in 2021, but fell to 32% in 2022 and 2023, and up a little to 37% so far in 2024. (Data is to May 2024 - ABS 5368 table 14a).

The difference is going to the rest of Asia, not just Japan, the re-awakening US military ally against China. Also on the rise are exports to South Korea, ASEAN, and India in the past couple of years.

The following chart shows monthly export volumes to Asian countries over the past ten years:

Although our largest single export buyer is still China, it is less than what we export to the rest of Asia (44%), which is the big opportunity for future export growth.

How does all this affect investors?

Geopolitics matters, especially as Australia is a major exporter of highly sought-after raw materials not just for peacetime industrial growth, but also for military build-ups and wars.

Wars may not be inevitable (c’mon humans – surely we can do better?!), but military build-ups certainly are.

Australia has been lucky (and well managed) enough to be able to prosper in peacetimes and in wartimes. When war does break out, we have been able to quickly switch our economic allegiances to align with political allegiances, and keep on prospering.

This been the case over the past couple of centuries, whether our exports were used for clothing, food, metals, or energy – illustrating Australia’s incredible diversity of raw materials.

Things change - it pays to be flexible

In the First World War, China and Japan were both allies. In the Second World War, China was an ally but Japan was an enemy. Now it is the reverse - Japan is an ally and China is a potential enemy.

As investors, our base case is that we are probably a long way from an all-out war between China and the US. It may not come to war of course - recall that the last great ‘cold war’ between the US/NATO and the Soviet Bloc ended peacefully, albeit with some peripheral wars in Korea and Vietnam and numerous other peripheral skirmishes.

Our base case is for continued trade and geo-political tensions, and ‘cold-war’ military build-ups – not just in China and the US, but also in Europe as a possible new ‘third force’. However, Europe has to deal with escalating internal political fragmentation, economic stagnation, and Putin first, so the notion of a European ‘third force’ is more idea than reality.

Cold war build-ups and occasional military flair-ups are good for commodities prices and good for Australia’s commodities exports.

For a picture of Australia’s changing export mix (by type of exports) see:

· Australia’s bounty: 400 years of exports. Is it just ‘luck’? Or masterful ability to adapt and pivot (15 Nov 2023)

On China’s role in our exports, see also:

· Chinese Steel Production - the Sydney Harbour Bridge Index (25 Mar 2024)

· China builds another ‘Sydney CBD’ every 3 days – with our rocks! (15 Sep 2023)

‘Till next time – happy investing!

Thank you for your time – please send me feedback and/or ideas for future editions!