Commodities matter! More than half of the 2,200+ companies listed on the ASX are miners (the vast majority are explorers with little more than a map, a compass, and high hopes, but a small number of miners do actually produce something).

Mining employs just 1% of the population (there are more baristas in Bondi than there are miners in the whole of Australia!), but more than half of the entire profits and dividends from the 2,200+ listed companies on the ASX came from just three iron ore producers last year (BHP, RIO, FMG).

This has not always been the case of course, but mining shares have always dominated our share markets ever since the earliest days of share trading in dusty out-back mining towns.

Australians have long been the biggest gamblers in the world per capita. This may be one of the reasons for our love of speculative mining stocks, or it may be an outcome.

Raw commodities exports made, and continue to make, Australia the richest country per capita on earth. We have always relied on raw commodities exports to earn the foreign exchange needed to import everything we use in our daily lives.

‘Diversified’ Luck

Unlike most ‘banana republics’, this vast continent we inhabit just happens to have been blessed with an enormous variety of different types of commodities – or the conditions ripe to produce commodities - from the land, the dirt below the surface, and the sea around us.

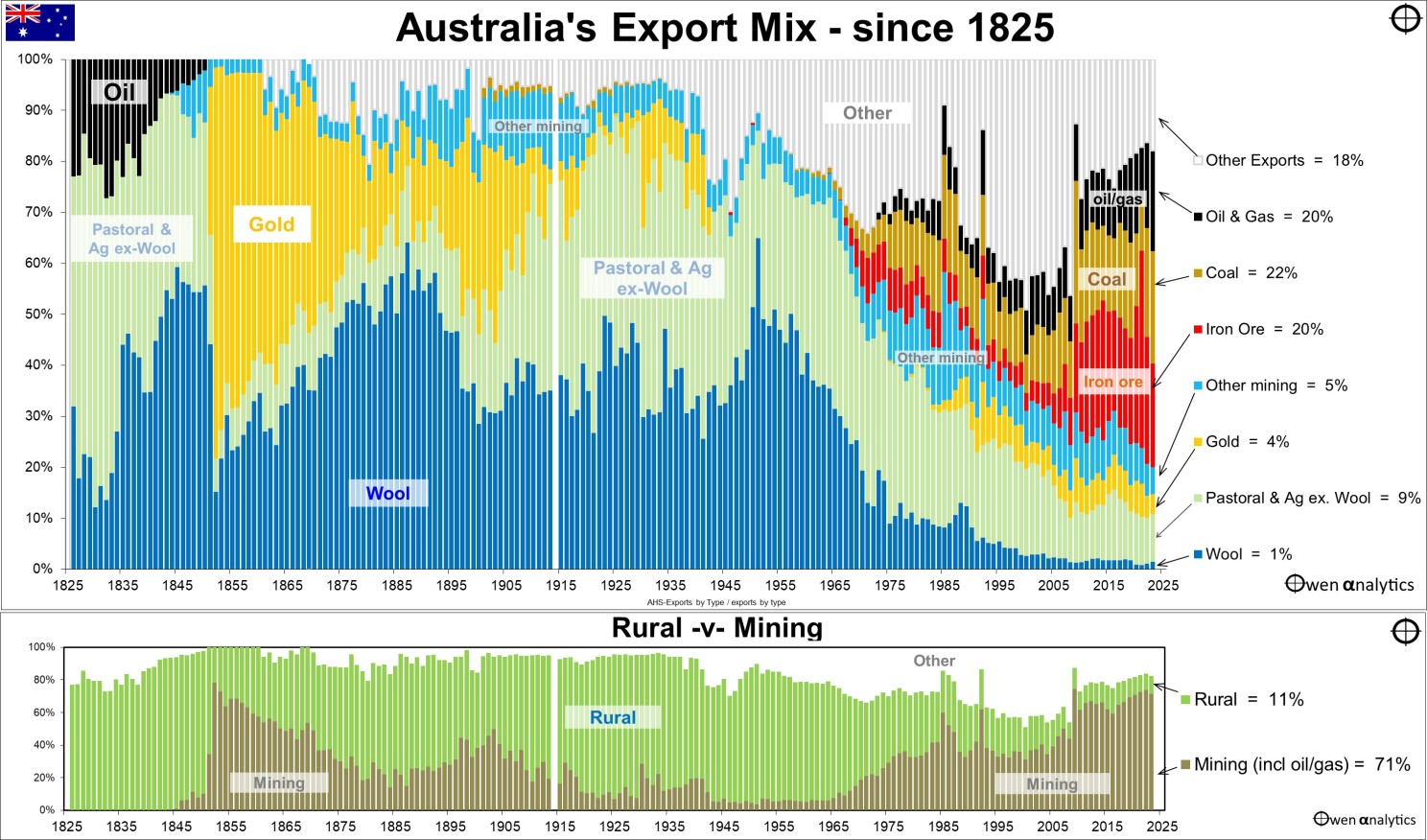

Here is our chart of Australia’s export mix over the past two centuries.

It is a remarkable story of dramatic shifts in our export mix over time – starting with oil, to crops, wool, gold, base metals in the 19th century, back to pastoral, wool, and crops for most of the 20th century, then the rise of East Asia built with our coal, iron ore, and base metals after WW2, back to oil and gas, and now ‘battery metals’ and ‘rare earths’.

It illustrates not only our vast diversity of natural resources, but also the ability to adapt and prosper from changing global economic and political conditions.

Just about whatever the rest of the world wants, we seem to find it!

Exports to China at least 400 years ago

What we now call ‘Australia’ has been exporting to what we now call 'China' for at least 400 years. Studies have shown that, from the 1600s or perhaps even earlier, regular fleets of sea-faring Macassan traders (now Sulawesi, Indonesia) bartered with the local Aborigines in northern Australia to source trepang (sea cucumbers) for sale into what we now call China.

After British colonization of Australia, this export trade was taxed increasingly heavily, and the trade finally ended in 1906 when the South Australian Government refused to issue fishing licenses to foreigners.

Why end a profitable trade that had been thriving for centuries?

British monopoly on trade

British colonial policy was designed to benefit Britain’s interests. Trading with anyone but Britain was outlawed, as Britain had granted a monopoly over all trade between the Cape of Good Hope (South Africa) and Cape Horn (South America) to the East India Company, which was established in 1600 to seize, plunder, and colonize foreign lands for Britain. This included India, China, the rest of Asia, and the Australian colonies. In addition, private ownership of ships in British colonies was also banned.

We have no records of the volumes or values of this trade with China, or other trading with neighboring islands that no doubt took place prior to British colonization.

First 30 lean years after 1788

After the British arrived to establish a convict prison in Sydney in 1788, the first 30 years was spent searching for an export industry that could generate foreign exchange to pay for the colony’s imports required to develop the settlement.

Oil

The first major export after British settlement was oil – well before the first shipment of wool, gold, or any minerals. It was seal oil from Bass Strait seal fishing, and whale oil from deep sea whale hunting. These were taxed heavily by Britain in order to protect British whalers.

The seal oil and whale oil industries peaked in the late 1830s, but never recovered from the 1840s depression. It was not a scalable industry, it was subject to the vagaries of the weather, discriminatory British tariffs, and heavy competition from American whalers.

Wool

The ‘next big thing’ was wool grown for the British market.

During the Napoleonic Wars, Britain had switched from breeding sheep for wool for clothing, to breeding for meat (mutton). As a result of this switch, after the Wars ended, Britain needed a new source of wool to compete with cheaper Spanish and German wool, to feed Britain’s new mechanized, mass-production textiles industry. Australian wool filled the gap.

Wool was Australia’s largest export earner almost all of the 130 years from the 1830s to the 1960’s. Wheat and other grains also played a major role.

Rural exports increased significantly from the early 1900s with the introduction of refrigerated ships that greatly expanded the range of exportable farm products.

Gold

Gold was our largest export earner in the second half of the 19th century. We had four major gold booms:

- the Victorian gold rush in the 1850s (it got us out of the 1840s global depression)

- Mount Morgan (Queensland) in the 1880s (it got us out of the 1870s ‘long depression’)

- Coolgardie/Kalgoorlie (Western Australia) in the 1890s (it got us out of the 1890s global depression),

- Gold also enjoyed a boom in the 1930s after the depreciation of Australian currency in 1931, and Roosevelt’s depreciation of the US dollar against gold in 1933 (it got us out of the 1930s global depression).

(We will cover the extraordinary and fortuitous role that gold mining played in helping us out of global/local economic depressions in another story!)

Agriculture-Mining mix

The lower section of the chart shows the changing mix between rural and mining exports over time.

Rural exports have contributed the lion’s share overall, but mining dominated during two periods. The first was between 1851 to 1870 (mainly gold), and the second has been the period since 1980 (mainly coal, iron ore other industrial metal ores, plus oil/gas).

The turning point was 1960. At the time, wool made up 50% of total export revenues, but the lifting of the iron export embargo in 1960 diversified the export base and dramatically reduced Australia’s vulnerability to the vagaries of the weather.

Aside from gold, other mineral booms have included:

- copper in South Australia in the 1840s,

- silver and lead from Broken Hill in the 1880s and 1890s,

- coal and iron ore from the 1960s - initially to Japan 1960s, then to Asian Tigers, then China from the 2000s,

- the oil/gas industry also expanded rapidly following the discovery and development of Bass Strait oil wells from the late 1960s, and more recently, natural gas (LNG) in WA, NT, and Queensland.

Australia may have got rich ‘riding the sheep’s back’, but it is a far more diversified and robust export mix now. Wool contributed 65% of total export revenues in 1951, but only 1% today.

High-value to low-value

Up until the middle of the 20th century, our exports were mainly high-value – wool and gold. High values per tonne overcame the high costs of transport to distant markets.

In contrast, from the 1960s onward, our exports have mainly been the lowest value materials of all - dirt and rocks, where transport costs make up most of the sale price we obtain.

Coal and iron ore, even at relatively ‘high’ prices of $100 USD per tonne, are still only one 600,000th (0.00017%) of the value of the same weight of gold, and 150th (0.67%) of the value of wool.

Since the start of the first gold rush in 1851, Australia has produced a total of 15,900 tonnes of gold, or 823 cubic meters (a cube just 9.4 meters on each side, which is about the size of an average house). In contrast, Australia now ships that much iron ore to China every ten minutes!

Australia became the wealthiest country on earth on high-value exports (gold, wool) in the 1800s. However, with low-value exports now, we need to dig up and ship literally whole mountains of dirt and rocks each year just to maintain the same level of export revenues and living standards.

Australia – richest nation per capita – from commodities

In just one hundred years, raw material exports took post-settlement ‘Australia’ from a struggling prison colony to be the richest (highest income) nation in the world per head of population by the late 1880s.

To this day, Australia is still the richest country in the world per capita (based on median income, and also median wealth per head), thanks to our commodities exports.

In addition, thanks to tax revenues from our export bounty, Australia is the only ‘rich’ country in the world running a government surplus (apart from Switzerland), while the US, UK and Japan are at the bottom of the table, running ‘banana republic’ deficits of around 6% of GDP.

Australia’s continued wealth and prosperity rely on continuing to find and exploit new types of materials that the rest of the world wants.

Look around you – almost everything in our homes, offices, shops, schools, factories, restaurants, hospitals, etc, is imported. The few items that are made from local ingredients (eg. fresh food, timber) was all picked, cut, processed, packed, prepared, transported, frozen, cooked, etc, with imported machinery.

We need exports to pay for all of these imports to support everything we do in our daily lives.

‘We do rocks!’

There’s nothing wrong with this – our ‘comparative advantage’ is raw materials.

We let other people in other countries magically transform our raw materials into useful stuff that we re-import back as finished goods at many thousands of times the price we got for the original exports.

Dumb, smart, or just lucky?

It may sound 'dumb', but it has made Australia the richest country in the world per capita for the past 130 years!

Minerals are not 'renewables'. Every ore body is a finite resource that will be depleted one day. So far, when one mine closes, or when the demand for one mineral subsides, we find another one!

Our oil has run out, but now we have natural gas!

The world is shifting from fossil fuels to batteries and renewables, and now we have 'battery metals' and 'rare earths'!

The post-Fukushima world is now shifting back to nuclear, and we have uranium!

Chances are that in another hundred years, other people in other countries will want new kinds of raw materials that we don't even know exist yet, but we will probably find it somewhere here!

It just happens that this vast rock in the middle of the ocean seems to contain an incredibly wide variety of stuff that other people in other countries happen to want, and we have it when they want it!

Can our incredible run of luck continue?

Will we continue to find useful and exportable stuff in, under, or around this vast continent?

History would suggest we probably can and will.

Australia is a vast continent, and the mining holes may be ugly and destroy cultural sites, poison rivers, habitats, ecosystems, and do all sorts of other types of environmental damage, but, in terms of sheer magnitude, the mining holes are still minuscule relative to the size of the country. Thus far anyway.

We have probably not even 'scratched the surface' yet – literally.

The up-side - Commodities in an inflationary world

Aside from fueling global inflation, rising commodities prices are particularly good for commodities exporters like Australia. Provided, of course, that we continue to find stuff that people in other countries want to buy.

Commodities exports will not only help lift overall economic growth but will also create opportunities for investors in commodities-related companies.

The down-side – bubble/bust cycles

The first downside is that commodities markets are prone to wild boom/bust cycles in which lots of money can be made and lost.

The key to success with investing in commodities markets (including commodities related companies) is understanding these commodities cycles and getting the timing right.

All commodities boom/bust cycles are driven by the same four factors – demand, supply, time lags, and leverage, although the details obviously differ in each case.

Here is one example – Case study: 2003-7 Uranium-Paladin bubble & bust. Before jumping into the next bubble, what can we learn from the last one?

The down-side – government interference

Many younger readers may not realize that Australia did actually make stuff in the past (clothing, appliances, cars, ships, airplanes, computers, machinery, etc). But that was behind high protection barriers from the early 1900s and especially during and following the First and Second World Wars when shipping lines were closed off.

Protection led to widespread inefficiencies and sucked capital, labor, and taxes out of non-protected, productive industries to prop up inefficient, protected industries.

Virtually all manufacturing industries died when the protection barriers were removed following the economic reforms of the 1980s and 1990s. Those reforms threw off the shackles of protection and kicked off a tremendous boom in productivity and efficiency, transforming Australia from an inward-looking sheltered workshop for inefficient protected industries into the outward-looking, flexible, dynamic economy we have today.

Nobody wants to go back to the bad old days of inefficient, protected, subsidized industries. Except governments!

The problem is that in a post-Covid, polarizing (perhaps de-globalizing) world, governments in many countries, including Australia, are now attempting to 'de-risk' their economies and shift toward 'self-sufficiency' by protecting and subsidizing local industries again.

In many cases, they are attempting to start whole new businesses and industries from scratch with no existing business case and no successful models in other markets. Government interference always distorts capital allocation decisions, prices, costs, profits, and investment outcomes. Whenever governments try to 'pick winners,' there are a lot more losers than winners. The main losers are consumers who pay higher prices and taxpayers who subsidize the protected industries.

Distortions due to government protection and subsidies will probably have negative impacts, not only on individual commodities markets but probably also on our economy as a whole.