China builds another ‘Sydney Harbour Bridge’ worth of steel every 10 minutes!

If I had to pick a single number that has driven Australia’s economic growth, prosperity, living standards, tax revenues, ASX share market returns, and even house pieces, so far this century - it would be China’s steel production.

Why is steel so important?

Chinese steel production has been the single most important ingredient in China’s incredible urbanisation and industrialisation that has driven its overall economic growth, and this Chinese growth has been by far the single largest contributor to world economic growth this century.

It has especially benefited Australia’s growth in incomes, wealth, and living standards, because most of the iron ore and coking China uses to make steel is imported from Australia.

The wealth has come not only via dividends to Australian shareholders - which they distribute across the economy by spending it, or they deposit it in banks which then lend it out (on home loans that boost house prices, and business loans that boost investment and jobs), but it has also been the largest external source of federal and state government tax revenues.

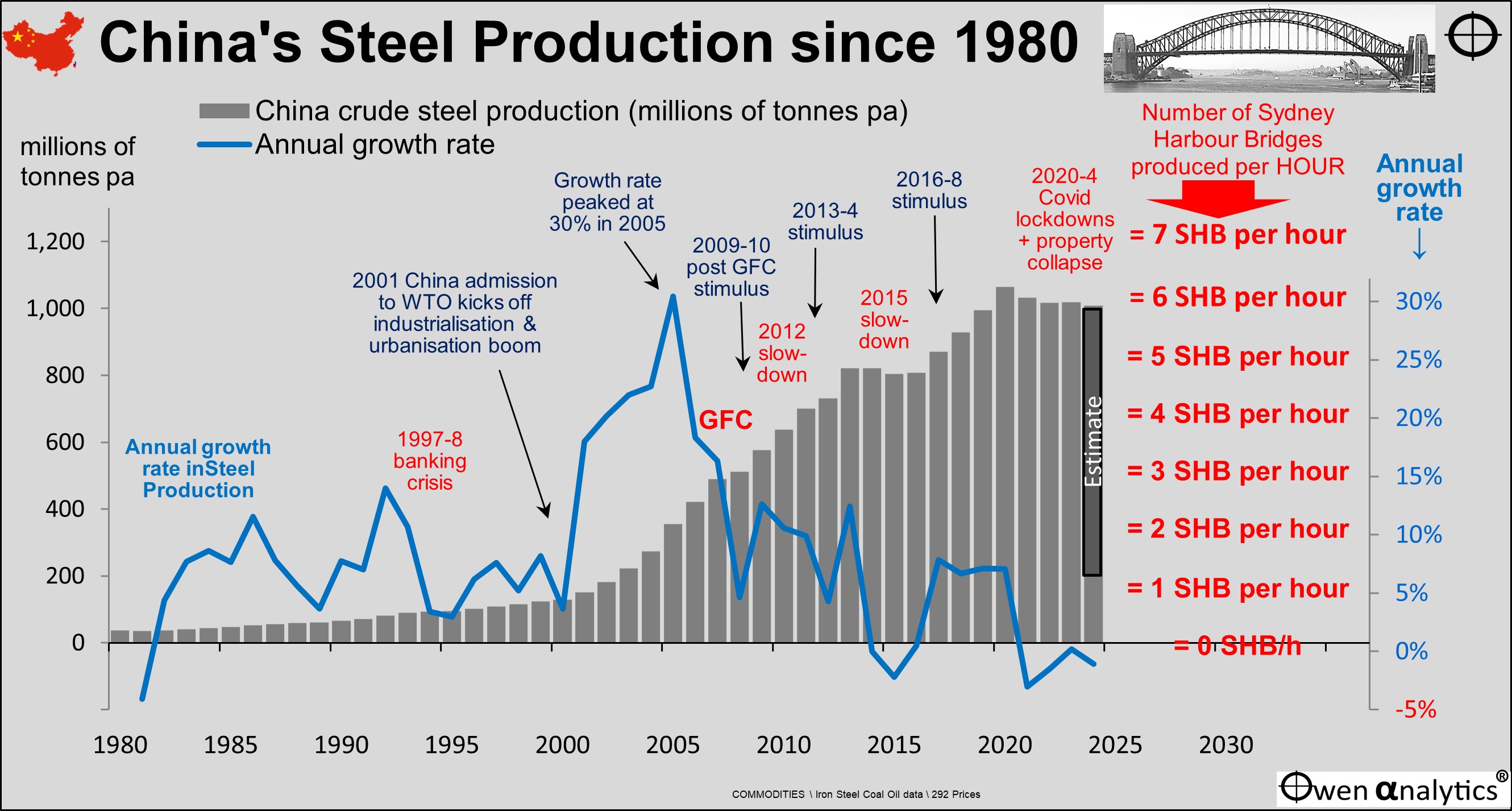

In today’s chart, the grey bars show China’s steel production in millions of tonnes per year, and the blue line shows the annual growth rate. The red numbers to the right indicate the steel production rate in terms of the equivalent number of Sydney Harbour Bridges worth of steel China builds PER HOUR!

How much steel?

This year, China will make 1 billion tonnes of steel (I estimate around 1.008 billion tonnes based on production so far this year).

How much steel is that? 1 billion tons of steel is 26,000 ‘Sydney Harbour Bridges’ worth of steel.

In the 10 minutes it will take you to read this story, China will have built the equivalent of one ‘Sydney Harbour Bridge’ worth of steel. That is simply mind-blowing!

One Sydney Harbour Bridge of steel

The Sydney Harbour Bridge is made from 38,000 tons of steel (most of which was imported from England because BHP could not produce enough). The bridge took eight years to build and was opened in 1932 in the depths of the 1930s Great Depression.

(As an aside, the huge cost of building the bridge was one of the main reasons the New South Wales government defaulted on its State debts in 1931, and then the Commonwealth also defaulted on its national debt after taking over the NSW debt).

Today, China is building the equivalent of one Sydney Harbour Bridge worth of steel every 10 minutes. That is the equivalent of building six Sydney Harbour Bridges every hour, 12 hours per day, 365 days per year. That’s 26,000 Sydney Harbour Bridges per year.

With that much steel, China builds a lot of bridges, factories, apartment blocks, cars, office towers, airports, military islands, war ships, tanks, bombs, etc (we will get to the military aspects below).

There are two main issues for investors - 1) China’s future steel production; and 2) Australia’s share.

1) China’s future steel production levels – much more important than ‘GDP’

China’s steel production is much more important to Australia than Chinese overall ‘GDP’ growth or any other number. Why?

Because even when Chinese growth slows or even stops dead, it doesn’t really matter because the main policy tool the Chinese government uses to stimulate activity and employment has been, and still is, infrastructure spending. That means construction, where the core ingredient is steel, made mainly from iron ore and coal from Australia.

Japan – on repeat

It was the same with Japan in the second half of the 20th century. In the post-WW2 era, Japan was the great ‘emerging market’ that powered global growth, and drove Australia’s prosperity (just like China in the 21st century). Japan’s incredible construction and industrialisation boom was built with our exports, and Japan was Australia’s largest export customer from 1965 onward.

But, when Japanese growth hit the wall, stopped dead in 1990, and flat-lined ever since, Japan still remained Australia’s largest export customer for the next 20 years, until it was finally overtaken by China in 2010.

Japan remains our second largest export customer even now, despite its flat-lined economic growth over the past 34 years, and declining population.

What matters is not some theoretical ‘GDP’ growth number. All that matters is how much rocks, dirt, and gas they buy from us.

What happened to Japan since 1990 is now happening to China. The property construction/finance bubble has burst, the population is aging and declining, and GDP growth has collapsed, but the government will probably still resort to infrastructure and construction to keep the workers employed, quiet, and compliant, just like they have done in the past 20 years.

China’s steel production growth pattern

Chinese steel production grew by an average of 7% per year during the 1980s & 1990s, but then surged to 20% growth per year between 2001 and 2007 following China’s entry into the World Trade Organisation in 2001, which accelerated its booms in manufacturing, exports, and urbanisation.

After the 2008-9 global financial crisis, growth rates in steel production then fell back to around 5% per year, and that includes the massive infrastructure spending boom funded by the post-GFC stimulus program.

China’s number one policy tool to stimulate economic activity

Every time there is a slowdown, the government has in the past, and probably will in the future, resort to ramping up construction to boost activity and employment. For example, China’s infrastructure boost in the GFC was what saved Australia’s economy from a deep ‘recession’ (although our local share market and currency fell by more than almost every other country in the GFC).

Chinese growth, and commodities prices, peaked in 2011, but slowed in 2012, so stimulus was ramped up in 2013-4.

Growth slowed again in 2015 (and the commodities prices slump on that occasion triggered a string of losses and bankruptcies in oil/gas and mining companies everywhere, resulting in share price falls around the world and a global ‘earnings recession’), so Chinese stimulus was ramped up again from early 2016.

Then in 2018-9, signs emerged of another slowdown in China’s growth (thanks, in part, to Trump’s trade wars) and this showed up in slower growth in steel production.

In the 2020 Covid scare, China once again ramped up infrastructure spending, and with it, steel production and iron ore imports from Australia.

2020 Covid stimulus peak

China’s steel production peaked at 1.065 billion tonnes in 2020. The government cut production in 2021, partly to reduce carbon emissions, but also because domestic construction activity was already slowing and the government was wary of allowing the smaller, loss-making steel mills to continue to over-produce and rack up more debts.

Production also slowed in 2022 with the collapse of the residential construction sector and the crisis with several major construction groups (Evergrande, followed by dozens of others), and the Chinese economy posted a very slow 2.9% for the year, the worst since the 1970s.

Iron ore to the rescue, again!

But it didn’t matter to us, because China still produced 1 billion tonnes of steel, and our miners posted record profits and dividends.

More than half of the combined profits and dividends from the entire 2,200+ companies listed on the ASX came from just three companies – BHP, RIO, and FMG, almost entirely from iron ore exports to China.

While the rest of the world posts massive government deficits, we’re in surplus! All thanks to China building another Sydney Harbour Bridge of steel – every 10 minutes.

In early 2023 China announced a grand, but belated ‘re-opening’ after their extended Covid lockdowns. This stalled, so the government once again had to crank up the infrastructure construction engine.

From April 2023, the government capped steel production at 1.018 billion tonnes per year to prevent over-production and glut. That’s still a lot of steel.

Struggling to shift from construction to consumer consumption

Over the past decade, the Chinese government has being trying to shift the engine of Chinese economic growth away from construction and toward consumer consumption, like in western economies.

This has never worked in China, for a variety of reasons, including declining consumer confidence, caused by a range of factors including declining housing prices (the main store of household wealth), millions of people losing their housing deposits in abandoned, partially-completed apartment blocks, declining share prices, high youth unemployment, a rapidly aging population with few government services and safety nets, harsh government crackdowns on high profile business tycoons, and also crackdowns on public dissent, in building Xi’s surveillance state.

With consumer spending remaining chronically weak, the government just reverts to plan A: ramping up construction again. Much easier and quicker, and better for our rock diggers!

Longer term outlook

Aside from the regular cyclical rises and falls in construction cycles, on a broader level, China’s tremendous boom in industrialisation and urbanisation has slowed because more than half of its population has already been urbanised.

On top of that, the west is ‘de-coupling’ or ‘de-risking’ their supply chains to reduce reliance on imports from China. China’s glory days of high overall GDP growth rates are well and truly behind it.

Even after thousands of empty apartment blocks have been bulldozed across China, there are still countless thousands of empty buildings, and probably dozens of ‘ghost cities’ – all built with our rocks.

But it doesn’t really matter. The government has little choice but to keep on building stuff (and even exporting surplus steel it doesn’t use), rather than cut production and risk even higher levels of unemployment and unrest.

Shift to military spending

This time, rather than yet another round of large-scale domestic stimulus, which Xi Jinping knows will just result in even more debts, and bail-outs for recalcitrant billionaires he wants to silence, Xi is instead focusing on extending China’s military and territorial reach via is military/trade ‘Belt & Road’ program across Asia, the Pacific, into Africa and even Europe and Russia.

China’s accelerating military build-up, plus its Belt & Road expansion program, are boosting demand for our rocks not only within China, but also in Belt & Road vassal states, plus other countries that are building up their defences against an expansionist China. This includes our likely next big export market - India.

For these reasons – domestic infrastructure spending plus military/Belt & Road spending – China’s steel production is likely to be supported at or around current levels for a while yet, despite headline GDP growth numbers stagnating.

Just as Australia’s exports to Japan continue to thrive more than 30 years after Japan’s economy flat-lined permanently, Australia’s exports to China will also not necessarily automatically drop just because China’s economic growth flat-lines permanently.

2) Australia’s dominance

The second big question for Aussie investors (and policy makers), is: ‘Can Australia retain its share of the action?’

China has been trying desperately to reduce its reliance on our rocks in recent years, but there are few alternative sources of cheap, high-grade rocks, and this will probably be the case for some years to come.

In fact, in recent years, Australia has increased its share of Chinese imports at the expense of our main competitors - Brazil’s iron ore, and South Africa’s coal.

In the coming years there will be major new supplies of iron ore from Guinea (Simandou, being developed by RIO and China), but there are also huge new mines coming in the Pilbara (eg the Wright/Bennet family’s Rhodes Ridge, also with RIO), probably with greater reserves, higher grades, and lower cost than Guinea.

Major additions to supply, of course, is bad for iron ore prices, with demand probably remaining around flat, but this story is about volumes, not prices.

China is hedging its bets on suppliers – it has large stakes in each of the major ‘Australian’ producers, and it is also the main foreign investor in countries developing new supplies.

(The same is true for other metals exported by Australia, like nickel, now threatened by Chinese-backed mines and plants in Indonesia. The difference is that with iron ore, unlike nickel, Australia still has a significant cost advantage).

Geo-politics

Probably the biggest perceived risk to our iron ore exports to China will be Australia’s response if China invades Taiwan. Our response will depend largely on who is in the White House at the time.

I call this a ‘perceived’ risk because the reality may turn out to be very different to what people fear, even if all Australian exports to China cease suddenly.

This is another story for another day, but for a brief look at how Australia’s exports to countries that became enemies in WW1 and WW2 affected our total exports, see:

(Spoiler alert - in the case of both of the World Wars in the 20th century, despite Australia relying heavily on exports to Germany at the outbreak of WW1, and to Japan at the outbreak of WW2, Australia’s export volumes and prices actually boomed during both Wars!)

Meanwhile, in the time you took to read this story – China produced another Sydney Harbour Bridge worth of steel – with our rocks!

See also: