Last week I wrote about the Virgin Airlines disaster for shareholders. That was only half of the story of Virgin's last shot as a listed public company.

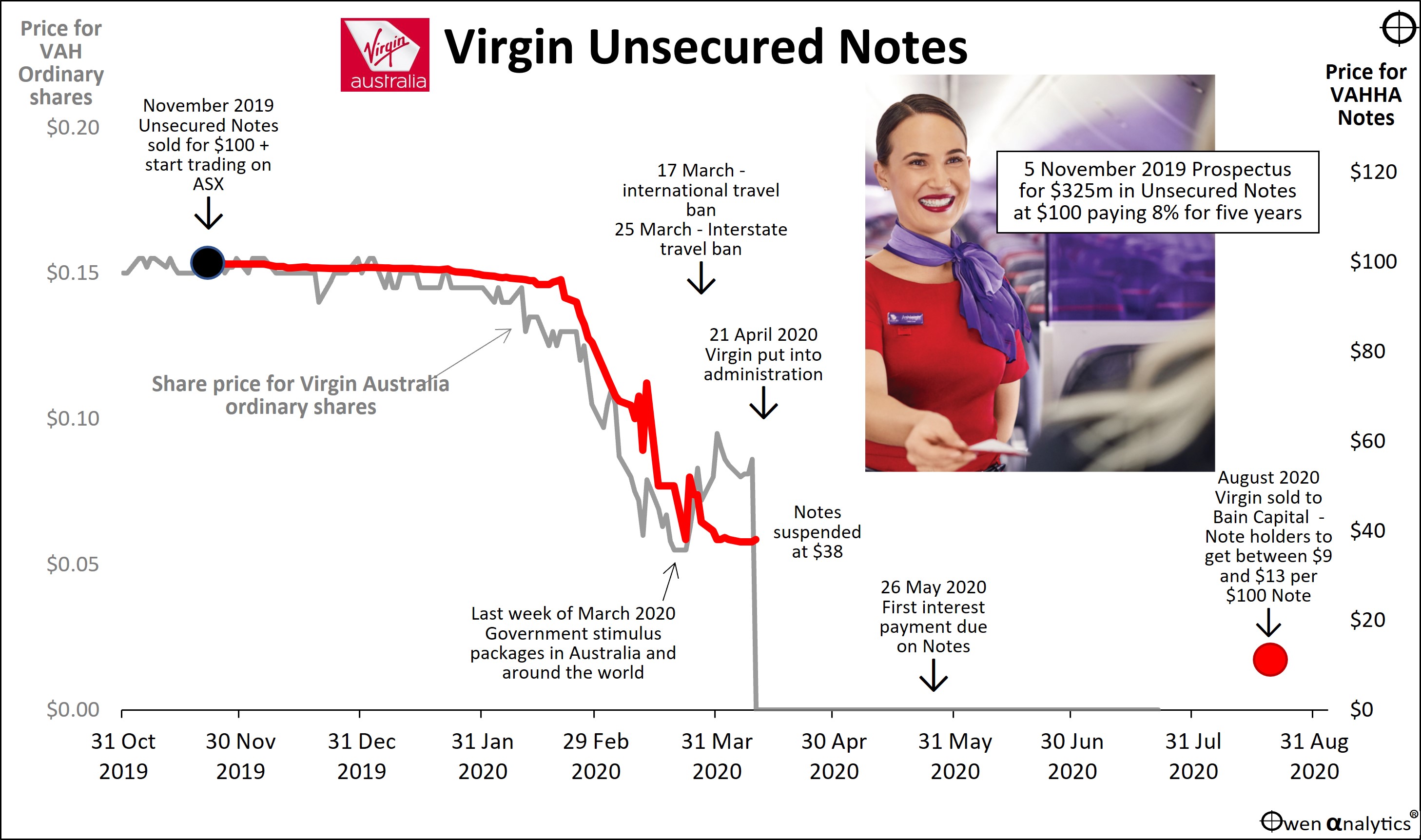

Here is the other half the sorry tale - the fate of the buyers of $325m of Virgin Notes - on the debt side of the balance sheet.

It makes a great case study in high-yield / high-risk debt. Are there any new lessons to be learned?

As Virgin Airlines is once again being shopped around the market trying to raise more money from investors to have another go as a listed company, I published a story last week on what happened to investors last time. See -

That story covered the losses for shareholders (equity), but that was only half of the story tale.

Tooday I will look at the equally disastrous story for investors on the debt side of the balance sheet. Retail investors were lured into buying $325m of ASX-listed retail bonds (‘unsecured Notes’) that were issued when the airline was already in the latter stages of a death spiral toward crash landing.

Diversification

One of the golden rules for bond investing is diversification – to spread risks across dozens of different companies in different industries, sectors and even countries, to try to minimise the impact of any one major event or crisis.

Everybody is aware of the importance of diversification with equity investing (shares), but it is even more important for bonds (debt), because bonds have no upside, only downside. With bonds, the most you will ever get back is the set interest payments plus the face value of the debt at maturity, so it is all about diversification to minimise the downside risk.

Understand the accounts

Another golden rule for equity and debt investors is to analyse the accounts of the company, understand the risks, and price the risk accordingly.

As the holder of bonds or notes (debt), you are a lender so, like any professional lender, you need to investigate and understand the borrower’s business, accounts and key people.

When analysing a company, the golden rule for annual reports and prospectus is always the same - only ever read the financial section at the back – and the Chairman’s report for a laugh. (No matter how good or bad the accounts are, the Chairman’s report always has glowing statements that the company: ‘. . .is on the cusp of a new era of growth. . .’!

The first half or two thirds of company annual reports and prospectus is just marketing fluff and should never be read because its whole purpose is to cover up the real story and divert you from the numbers. It is ok to briefly flick through the marketing fluff, but only to observe how much money they are wasting on marketing fluff – never actually read it. EVER.

Rip out the marketing fluff but don’t throw it out – put it in the recycling bin, so it can at least be turned into toilet paper, where it is more useful!

No fraud, just a bad business

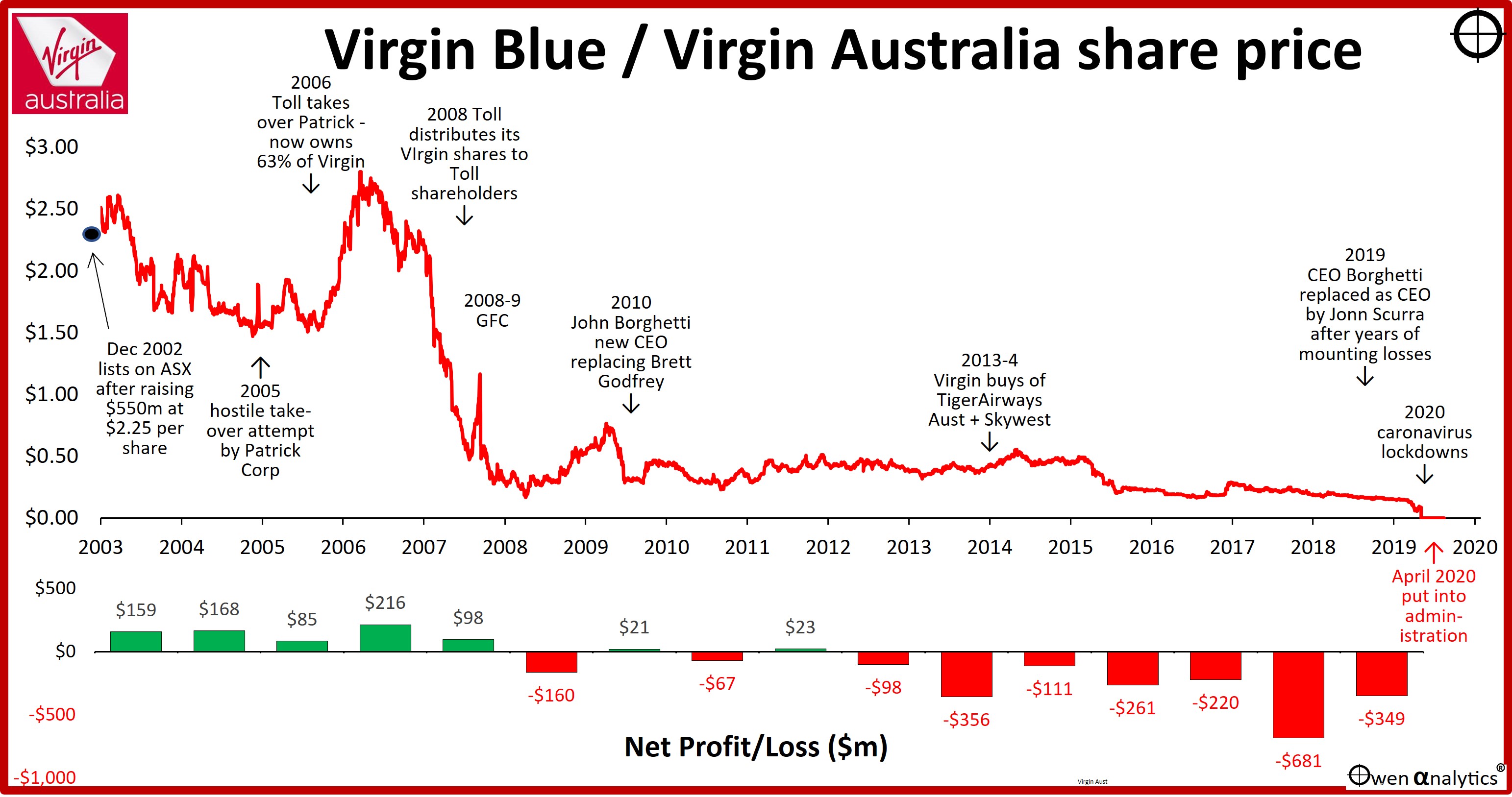

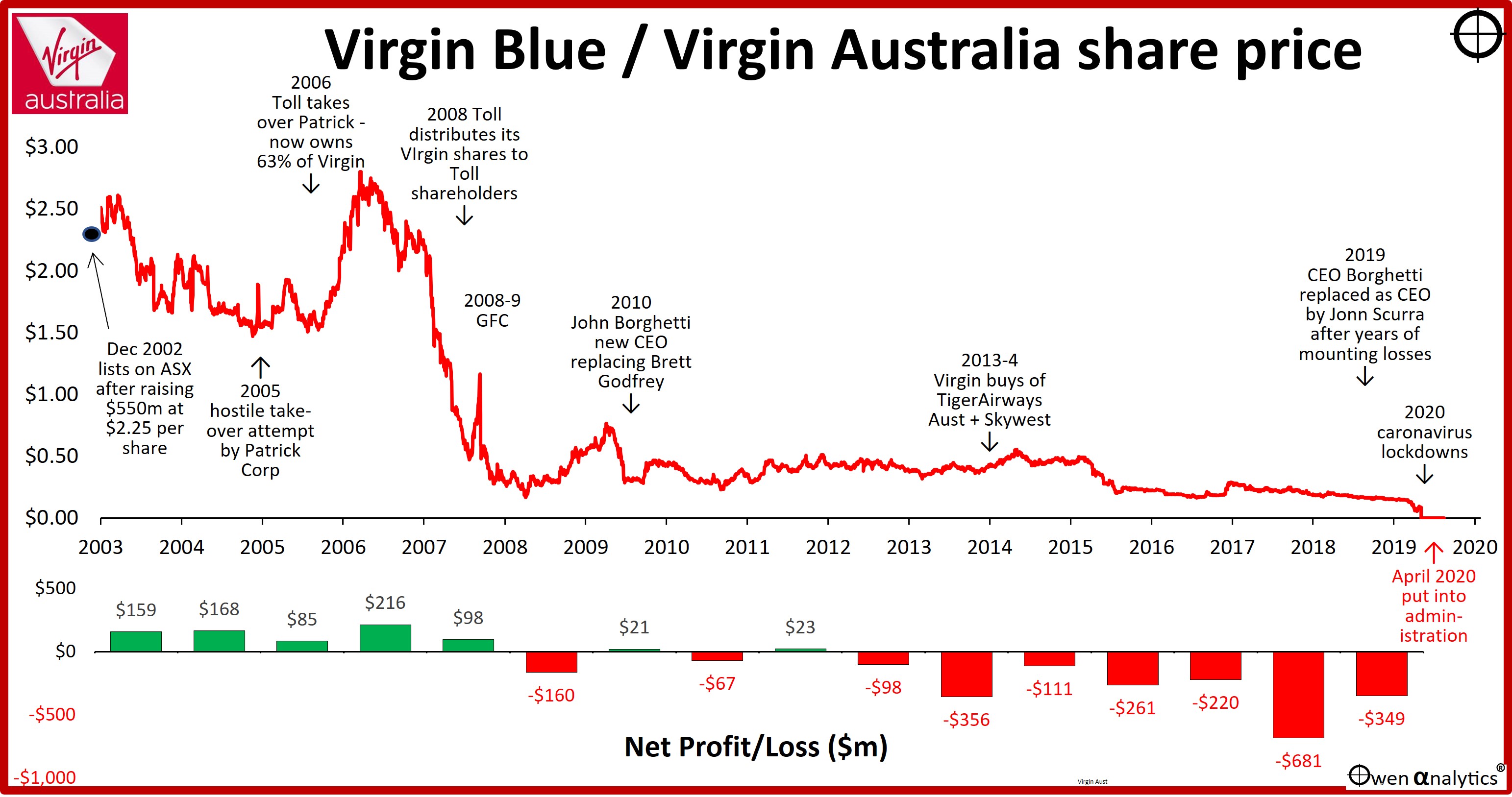

In this case there was no fraud or non-disclosure on the part of the borrower (Virgin). It was a bad business and had been a bad business for a more than a decade. (Refer to my previous story on the full history). The parlous state of the business and accounts were clearly disclosed in a decade of freely available annual reports.

In the prospectus for the Virgin Notes, after 74 pages of marketing fluff at the front, the financial section of the report was a flashing red warning to run a mile from this thing because it clearly laid out the dire financial condition in horrible detail.

Don’t believe me? Here is the 2019 prospectus for Virgin Notes.

The Profit & Loss (page 77) outlined the huge ongoing losses, the Balance Sheet (page 78) showed the mounting pile of debts, and the Cash Flow statement (page 80) confirmed that it was limping along by continually raising more and more debt.

It was a slow-moving plane wreck waiting to happen. Or in this case, a fast moving one, as the lenders (debt holders) were to find out very quickly.

You were warned

The prospectus noted the loss-making history of the company and even helpfully advised potential investors that the ‘loss position may continue or increase in future periods.’ (page 22).

The prospectus was also full of warnings about the risks – in pages 21-23 and 94 to 110. These sections painstakingly itemised and described no less than 48 different types of risks involved.

It had been a financial basket case for more than a decade – posting big losses and surviving by borrowing more and more each year. And that was during the good times – a period of economic growth and booming travel and tourism, before the coronavirus pandemic.

The company of course blamed Covid, but it was already a dead duck

By 2019 it was still running big losses and running out of options to borrow more to cover the losses. Regular lenders and banks had turned off the taps.

The company’s own shareholders (five international airlines) knew the company’s accounts inside out, and they knew the airline industry inside out – and even they came to their own conclusions that it was not worth saving by throwing even more money away on it.

If its own lenders and shareholders didn’t want to risk more money to save it – why would retail investors suddenly want to jump in and lend to it?

Promise a high yield!

Simple - the temptation of the juicy 8% yield of course!

They were ‘guaranteed’ to pay a fixed rate of 8% interest per year for five years until maturity in 2024.

This 8% rate was seen as too good to be true, and of course it was.

At the time of the issue, the cash rate in Australia was just 0.75% (yes, that was pre-Covid). Five year bank term deposits were paying 1.3%, and five year Commonwealth Government bonds were yielding just 0.80%.

High quality ‘investment grade’ companies were paying interest rates of around 3% on their Notes, but they don’t get much interest from retail investors with relatively low yields like that.

The promise of 8% on Virgin Notes brought a flood of eager amateur lenders – including thousands of ‘mum & dad’ retirees. The Notes were heavily promoted and sold by retail brokers for a juicy 1% sales commission by stockbrokers and financial advisers. Retail investors bought $325m of the Notes.

The notes started trading on the ASX as VAHHA in late November 2019.

Unfortunately, the ‘five-year’ Notes didn’t even last five months! The first interest payment was due on 26 May 2020, but by that time the company was long gone.

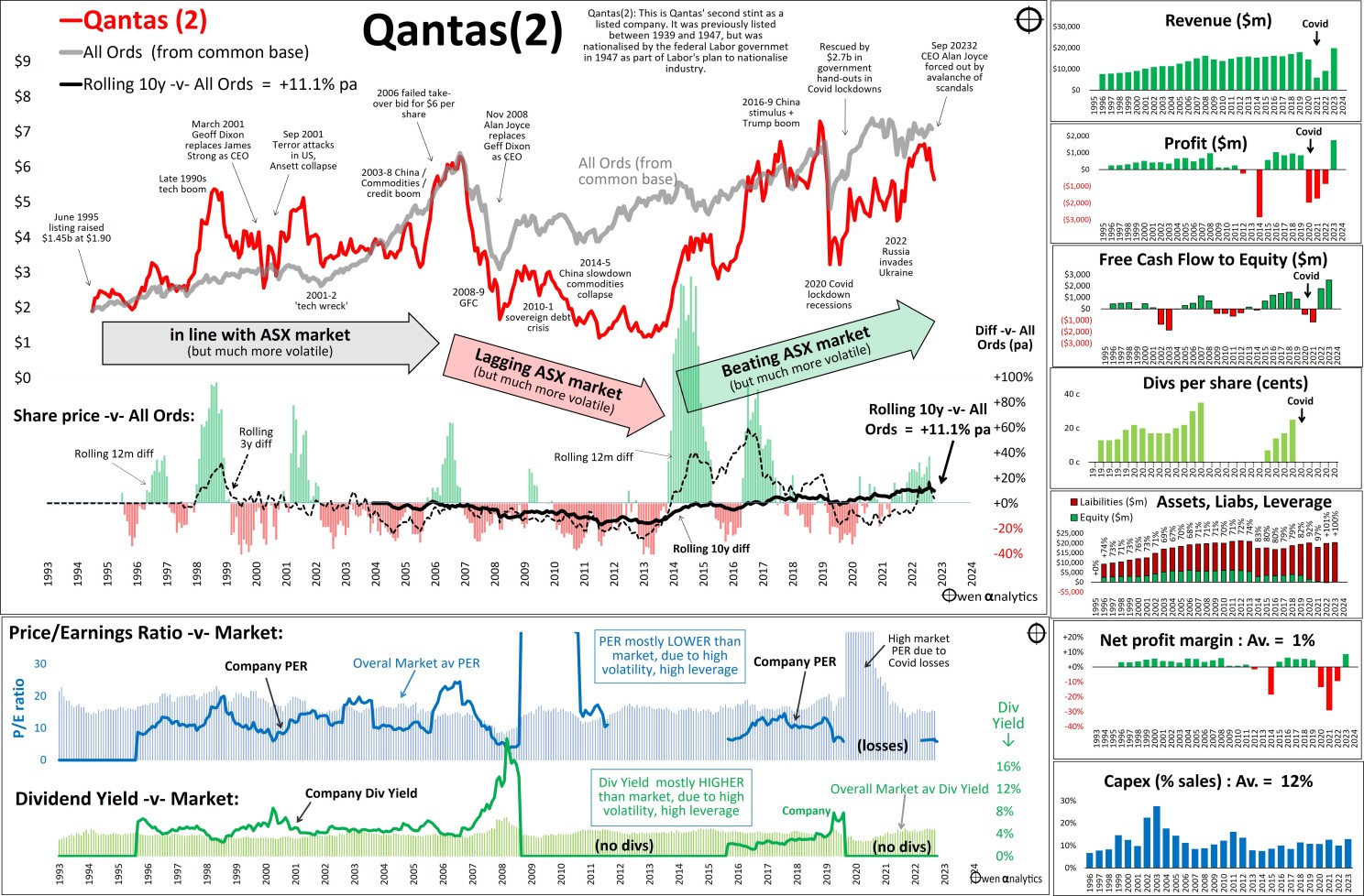

Even if there had been no virus pandemic, the company was likely to suffer a long slow death anyway, with mounting losses continually funded by ever-increasing debts. The under-capitalised, 90% foreign-owned Virgin was never going to win a price war against the former government owned, politically connected, protected national carrier Qantas.

Covid - the last straw

The pandemic arrived in early 2020 and Virgin’s end was accelerated. In the waves of lock-downs, international travel was banned on 17 March, and State borders were closed on 25 March. Less than a month later the company was put into administration on 21 April, with debts totalling $7 billion. The November 2019 prospectus disclosed debts of $5.8b, but somehow it racked up (or fessed up to) a further $1b in debts in less than five months.

After negotiating with creditors and potential buyers, the administrator sold the business in August to US private equity firm Bain Capital. Under the deal, the holders of the $2b worth of unsecured bonds and notes (including the VAHHA Notes) were to receive between 9 and 13 cents per dollar of face value and none of the promised interest.

This meant the VAHHA Note holders recovered about 7% of the $140 per Note they signed up for, being five years of interest at 8% per year, plus the $100 face value at maturity.

At least they got something. The ordinary shareholders received nothing.

Lessons?

There are no new lessons from this debacle, just reminders of centuries-old lessons, including:

- As a lender (bond or note holder) to a business, just like an equity owner (shareholder), you must make it your business to know everything you can about the business, its operations, assets, liabilities, and key people.

- Only flick through the marketing fluff to confirm evidence of waste. Rip it out, and read the accounts and fine print at the back.

- If something is offering to pay 8% when the cash rate is 0.75%, and it seems too good to be true – it is.

- Always ask the person selling it how much they are earning on the sale.

Here is the 2019 prospectus for Virgin Notes – enjoy!

For a broader background on Virgin Airlines and the fate its former shareholders, see:

· Virgin Airlines round 1: crash landing for investors (11 Jun 2024)

You may also be interested in -

· Qantas – My adventure with the over-geared, over-protected, cash-less bird! (6 Sep 2023)

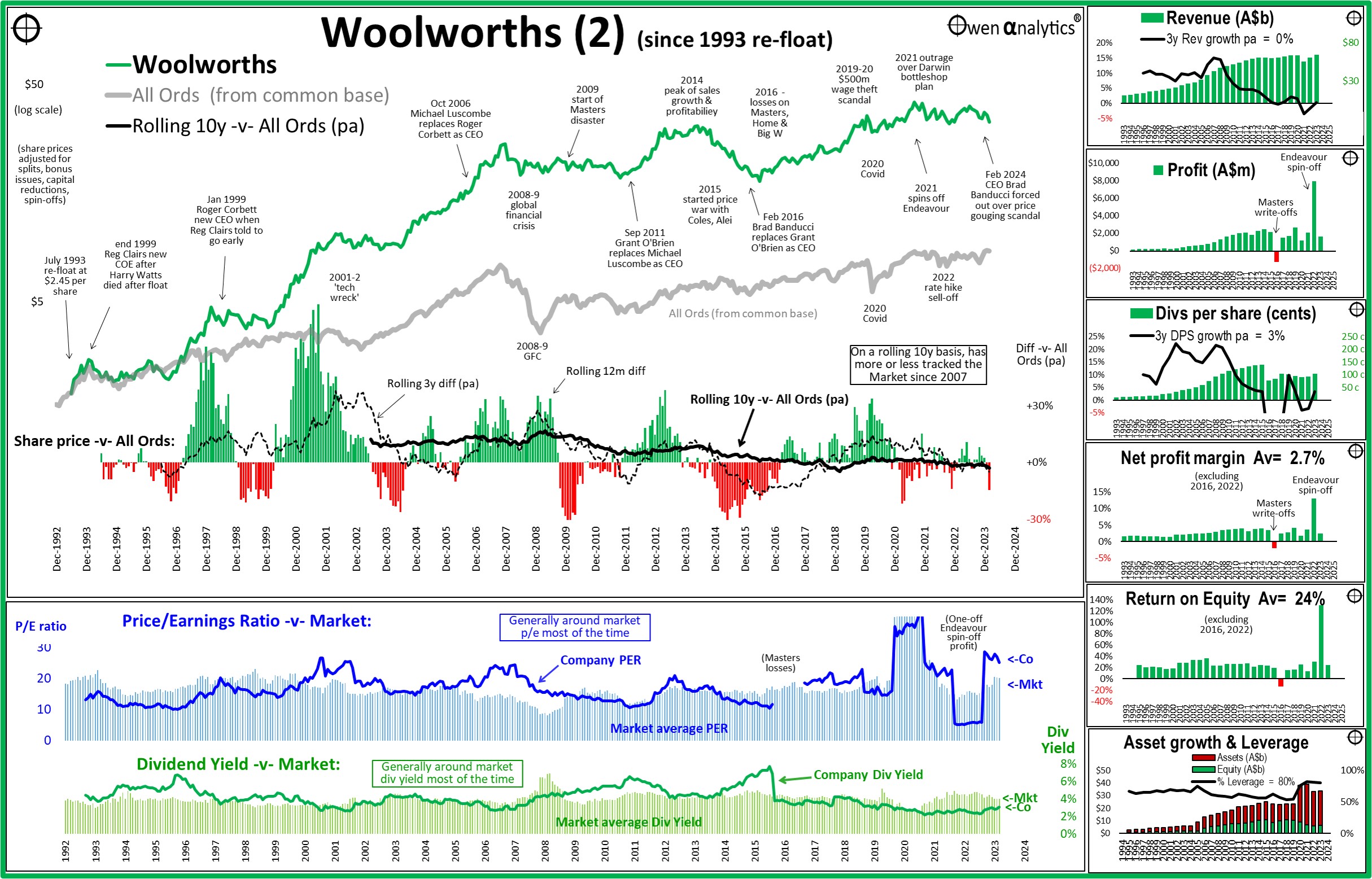

· Woolworths ESG case study: Duties to owners -v- suppliers, customers, staff (23 Feb 2024)

‘Till next time – happy investing!

Thank you for your time – please send me feedback and/or ideas for future editions!