Key points:

- How Woodside went from cash-strapped explorer to global giant and one of Australia’s biggest export earners.

- Still a wild ride for investors – as a leveraged bet on commodities prices, plus political risks.

- Despite huge profits and becoming a top-10 ASX company, still struggles to beat the overall market.

- Is it burning the planet, or an essential part of the transition to renewables?

In ‘Woodside Part 1: 1954-1980 – volatile speculative explorer & survivor’ (20 Oct 2024) we saw how the company started out as a tiny, under-funded explorer that had more failures than successes, but eventually discovered and developed one of Australia’s greatest resource finds – natural gas below the bottom of the ocean in the North West Shelf off the Western Australian coast, in the opposite corner of Australia from where it started. It was an extremely volatile ride for shareholders, where great fortunes were made and lost through numerous frenzied booms and devastating busts.

Today, Part 2 of the story looks at the period since 1980 when the company developed the enormous reserves of natural gas and went on to become one of Australia’s largest export revenue earners and an occasional member of the top 10 list of largest ASX listed companies.

For most of its seventy year life, Woodside was hailed as a great success story. However, over the past decade it has become a fossil fuel pariah, caught somewhere between two competing views - ‘gas is an evil fossil fuel that is burning the planet’ versus ‘gas is an essential part of the transition to renewables.’

(Some ‘ESG’/’ethical’ funds and ETFs filter out Woodside for the first reason, but others allow it in for the second reason – all very confusing! Rules and definitions of what is ‘good’ and ‘bad’ are very vague, and change constantly.)

I am not expressing a view either way on this, and I have never been a shareholder.

But as I study companies, and Australian listed companies in particular, and have invested in speculative mining stocks over the years, Woodside is a good case study as it has many features in common with more than half of the 2,200 companies listed on the ASX, and more than half of the 30,000 or so companies that have every been listed on Australian stock exchange in the past - as a volatile commodities play in which great fortunes are made and lost.

Development and production

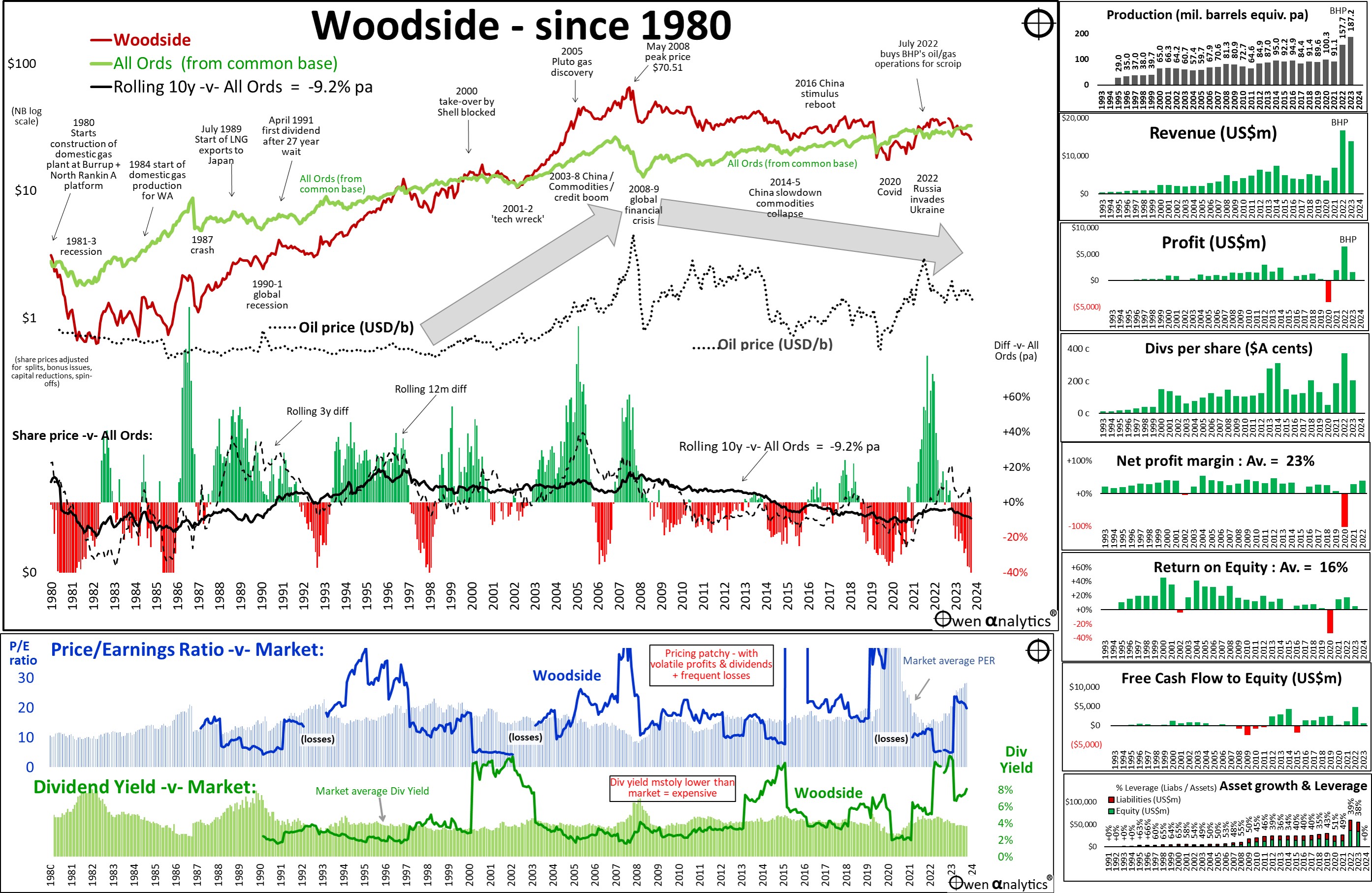

Today’s chart for Woodside Part 2 starts in 1980, when the company started construction of its North Rankin A platform, and gas plant on Burrup Peninsular for the domestic WA gas market.

In the upper section is Woodside’s share price (maroon), relative to the market index (green), and the oil price is in the middle section (black dots). As with all commodities producers, the share price is driven primarily by the commodities price, often more so than news relating to the company itself.

As with the chart in Part 1, the lower section of the main chart shows the share price performance of the company relative to the market index over three periods – rolling 12-months (green/red bars), rolling 3-years (black dashes), and rolling 10-years (black line).

Despite the major milestone in 1980 for the company, marking concrete progress at last after three decades in the wilderness as a speculative explorer, Woodside’s share price fell heavily in the early 1980s recession, down -80% from its 1980 mining boom peak. This was much worse than the general market fall, as it was still a speculative bet with no actual revenues yet.

Dividends at last!

In 1984 Woodside stated producing and piping gas to Perth for the domestic market. In July 1989, it started shipping LNG exports to Japan. Finally, in April 1991, the company paid its first dividend (at 5 cents per share). It was a rather long 27 year wait since the initial listing in 1954.

Share prices

In part 1, we saw that in Woodside’s first 26 years to 1980 as a revenue-less explorer, albeit with promising discoveries, its share price only just managed to keep up with the overall market index, but it was much more volatile through the frenzied boom/bust cycles along the way.

However, in the past forty years as a profitable producer, its share price has done no better.

Despite rising production, revenues, profits and dividends, its share price since 1980 also only just managed to match the overall market index, and it has still been a much more volatile ride through boom/bust cycles. From point to point, the share price from 1980 to today (September 2024) is still below the market index (green line on the main chart starting from a common base), but there are clearly two distinct phases, and they key is the oil price.

Leveraged bet on oil/gas price

Commodities producers are essentially leveraged bets on the commodity price (they have ‘operational leverage’ in the form of their fixed cost base, plus ‘financial leverage’ in the form of debt).

For explorers without revenues – like Woodside Part 1 - the leverage (sensitivity to commodity price swings) is even more pronounced. (Although the actual customer prices for oil and gas producers like Woodside are mostly based on long term contract prices, not the volatile market ‘spot’ oil price shown here on the chart, it is the spot and futures prices that drive market sentiment and therefore share prices. Gas and LNG prices are generally determined by reference to oil prices).

Phase 1 – rising oil prices

In the first phase (rising oil prices) - from the start of 1983 to June 2008 - Woodside shares beat the overall market by an average of +9.7% pa, while the oil price rose +338% from $32 to $140 (or +6.0% pa). Very handy indeed for shareholders in that phase.

Woodside peaked in the middle of 2008 at $70.51 per share – which was a horrendously expensive price/earnings ratio of 50 times earnings, and a dividend yield of just 1.5%. That was of course when the oil price peaked at $140 per barrel, immediately before the GFC recession.

In the GFC, the oil price collapsed, and so did Woodside’s share price. It has not been anywhere near that peak share price ever since. Sixteen years on, Woodside’s share price is still less than half of its 2008 peak, even though revenues, profits, and dividends are all much higher now.

Phase 2 – falling oil prices

However, in the second phase (falling oil prices) – since June 2008 to now (September 2024) – Woodside has lagged the overall market by an average of -9% pa, while the oil price has fallen by -49% from $140 to $72 (or -4.5% pa).

Not only do these two broad phases illustrate the fact that commodities producers are essentially a leverage bet on the commodities price over long periods, we can also see this over shorter periods like a year or a month or even a day. If the commodities price rises or falls in a particular day or week or month, for whatever reason (a supply constraint, or a change in outlook for global growth due to a rate hike or a GDP number in the US, Japan, or Europe or China, or sudden rate hike or bank collapse in a major market, etc), the share prices of producers and explorers almost always mirror the rise or fall in commodities prices, with the extent of the rise or fall driven by their operational and financial leverage to the commodity price.

For an example of this working in exactly the same way in the iron ore market on the share prices of the big three Aussie iron ore producers – see: Iron Ore – biggest driver of ASX market returns, profits & dividends – where are we now? (5 Sep 2024)

The solid black line in the lower section of the chart shows that the rolling 10-year price return relative to the overall market has been declining steadily since the 2008 peak, and is now decidedly negative. It has lagged the market by an average of more than 9% per year. That’s a very serious detraction from portfolio returns.

The key is to focus on the commodity price cycle, and share prices of producers will follow the same pattern.

2022 acquisition of BHP oil/gas assets

In July 2022, Woodside took over BHP-Esso’s Bass Strait oil/gas operations that BHP and Esso had run successfully for 50 years. These were the same Bass Strait oil/gas fields that BHP-Esso discovered and developed shortly after Woodside had run our od money and abandoned its unsuccessful decade-long search for oil/gas in Bass Straight and shifted instead to try its luck in the North West Shelf off Western Australia (see Part 1). In the Woodside-BHP deal, Woodside was doubling down on fossil fuels, but BHP was getting out.

In the 2022 deal, BHP shareholders received 1 new Woodside share per BHP share, and BHP distributed the new Woodside shares to BHP shareholders. This almost doubled the size of Woodside’s capital base and assets. The sudden jump in Woodside’s revenues profits and dividends since 2022 can be seen in the small charts to the right of the main chart.

Future prospects?

Usually the biggest determinant of share prices of commodities producers is the commodities price itself. Over the short term, oil/gas prices have been falling on deteriorating global demand outlooks, especially in China, Europe, and now the US. In tandem, Woodside’s share price has also slumped over the past year.

Beyond these cyclical effects, working in the other direction are gathering fears of escalation of wars(s) in the Middle East. However, the green transition issue is adding a whole new dimension to risks. Woodside appears to have doubled down on fossil fuels, and this has upset many shareholders.

It appears that world opinion has probably moved on from a hard-line ‘ban all fossil fuels immediately’, to a broad(-ish) emerging view that oil and gas are probably going to be around for many decades yet as part of the green ‘transition’. Various governments around the world have faced political backlashes when trying to move too quickly to eliminate oil and gas.

I am reasonably bullish on the government’s relatively supportive stance for mining, and even fossil fuels.

In Australia, both major sides of politics have been pro-resource exploitation and pro-growth for most of our history. There have been numerous examples of governments bending over backwards to help miners win business. Here’s one example of Woodside and the Australian government going ‘above and beyond’.

East Timor spy scandal

When negotiating for rights to explore and develop the hugely valuable Sunrise gas field below the waters off East Timor (now called Timor-Leste), Woodside arranged for Australian government agents (Australian Secret Intelligent Service) to spy on East Timor Prime Minister’s office and government officials, in the lead up to the 2005 Treaty. Spying for national security purposes is common (mostly we never get to hear about it), but spying on behalf of purely commercial interests is extremely rare and controversial.

As a result of this government/corporate espionage, Australia was able to gain a favourable 50:50 royalty split for 50 years despite the Sunrise gas field being much closer to East Timor (150km) than Australia (450km).

Rich Australia effectively screwed the desperately poor, war-torn East Timor for commercial gain, using corporate-sponsored government espionage! Woodside even paid Foreign Affairs Minister Alex Downer as a middleman (he became a ‘consultant’ to Woodside when he left office). Very nasty stuff indeed – all for the benefit of Woodside’s shareholders plus WA and federal government tax revenues. A pox on everyone involved.

Political risks

Despite this generally pro-growth and pro-resource exploitation stance of governments as evidenced by the spying scandal, when chasing green votes there is always a risk of governments unilaterally banning or restricting production or sales, or imposing quotas or fixed prices or caps. The recent international student cap fiasco has shown that governments are willing trash lucrative export industries (and tax contributors) to chase populist votes.

Even in the current politically charged fossil fuel / climate change debate, Labor has found ways to ditch its green promises and approve new coal and gas projects to score votes in the regions. Much will depend on the balance of power, and the power of the Greens.

Another unrelated political risk is native title actions (which at times are dressed up as environmental) to delay or prevent developments. For example, the Australian Conservation Foundation’s concocted ‘native title’ claim (the judge’s words, not mine) to try to stop Woodside’s Scarborough project. To date, the courts appear to be favouring a pro-growth stance, but such actions can add to costs, timelines, uncertainty, and scare away investors – just like Whitlam and Connor in the 1970s.

Positives

On the other hand, there are several potential positives. Aside from the general global shift toward accepting fossil fuels for longer, another positive is pricing.

Through most of its time as a producer, Woodside has mostly been more expensive than the overall market – higher price/earnings ratios and lower than market dividend yields, but very patchy due to volatile profits and dividends and frequent losses. However, of late, pricing has been on the relatively cheap side, reflecting the high political risks.

Current pricing and sentiment toward oil/gas producers is probably still based on an early phase-out of fossil fuels, which is probably going to turn out too bearish for current producers.

Finance

Another positive is loan finance. While most big banks are under pressure from shareholder groups, lobby groups and proxy firms to eliminate lending to oil/gas producers, private equity funds and private credit funds, are still major and growing lending sources of debt finance. These are not subject to the same ESG pressures.

Operating model

The Woodside formula has generally worked well to date. Its model is fairly unique in the oil/gas world. Whereas other oil/gas majors like Exxon, BP, Shell, etc generally fund developments themselves and stick to their slice of the value chain, Woodside’s model since the early days has been to use joint venture partnerships with global majors to put in most of the risk capital, then Woodside as a minority partner manages the vertically integrated operations from exploration, development, production, processing, and export marketing. This is sensible and it has worked to date.

Expansion mostly modest

Woodside has thus far mostly avoided the traditional Aussie disease of aggressive, overly-ambitious, ego-driven overseas expansion that so many other companies have fallen for – paying too much at the tops of booms, usually with debt, then writing off most or all of it when the booms inevitably collapse. This disease has afflicted a large number of Aussie companies over many years.

Woodside’s 2024 deal to buy and develop the Tellurian LNG project in the Gulf of Mexico appears not overly ambitious, and looks to be along the lines of the Woodside’s tried and tested joint-venture vertically-integrated operating model.

On the other hand, its deal to spend A$4b diversifying into ammonia in Texas appears to be purely for optics – to create the impression of diversifying away from fossil fuels. The size is relatively minor, and I would not be surprised to see it quietly sold off when the media spotlight moves on.

Debt reasonable

On the debt side, leverage has averaged around 40% in the recent decade. This may be modest for industrial companies, but probably on the high side for commodities producers with high fixed cost structures like Woodside. On the plus side, the company has always been careful with capital, as it has always been the junior partner to global oil/gas giants who have put in most of the cash for development.

Management a plus

Although initially run by Aussies during the early decades as a cash-strapped explorer, when Woodside shifted into production mode in the early 1980s, it has always had foreign CEOs – two Brits, then three Americans, all with deep international experience running enormous projects in extremely remote and inhospitable environments.

The current CEO Meg O’Neill, who was rushed into the CEO role in 2021 after Peter Coleman was forced out early, appears to have the courage to double down on fossil fuels and remain focused and undeterred (or ‘tone deaf’, depending on your view point).

Another positive for Woodside is that it is probably going to be well placed to compete for global projects. It is likely to have fewer competitors due to increasing difficulty/costs in raising equity and debt finance – ie it can probably be very selective and patient when choosing to expand.

The bottom line

As with all commodities producers, even with the best management and best operations, it is still essentially a leveraged bet on the commodities price – therefore highly sensitive to supply shocks, demand cycles, and lagged supply gluts from over-production after over-development booms triggered by price booms. It’s just the way commodities work.

Although the industry is driven by volatile commodities prices and cycles, and probably on the wrong side of history and in long term decline, this probably means more opportunities and more space for selective and patient investors, while the hot money is off chasing the ‘next big thing’.

But, like all types of investment, researching and understanding the underlying drivers and fundamentals is critical, and timing is everything. As in the past, there will be a time when Woodside makes sense tactically, but probably not at the moment.

‘Till next time – happy investing!

Soo also:

Disclosure: I do not hold shares in Woodside and have not in the past (aside from possible indirect holdings via passive/active funds/ETFs). This is certainly NOT a recommendation to buy, sell, or hold shares in this or any other company.

As always, my analysis is fact-based and intended to be as dispassionate as possible, regardless of whether or not I am a buyer, a seller, or holder. This quick, initial snapshot is no substitute for more detailed research.