The official inflation figures measure price inflation for a sample basket of items across the whole urban population of Australia. But this is just an average. Inflation is different for everyone.

On average, inflation for retirees is higher than CPI, but inflation for workers is lower than CPI.

Further, within these broad averages, no two households are the same, and no household is ‘average’. Different households experience different inflation rates based on their different spending patterns.

The prices of some spending items rise by much more than CPI, while others rise by less than CPI, and some items have even fallen in price over time.

Long term investors need to understand their own ‘personal inflation rate’, which may be quite different from the published CPI inflation rate.

Their own personal inflation rate will affect how much capital they need per dollar of living expenses, and how much they can afford to spend given their level of capital, to ensure that their living standards are maintained and not eroded over time, and that their money lasts as long as they do.

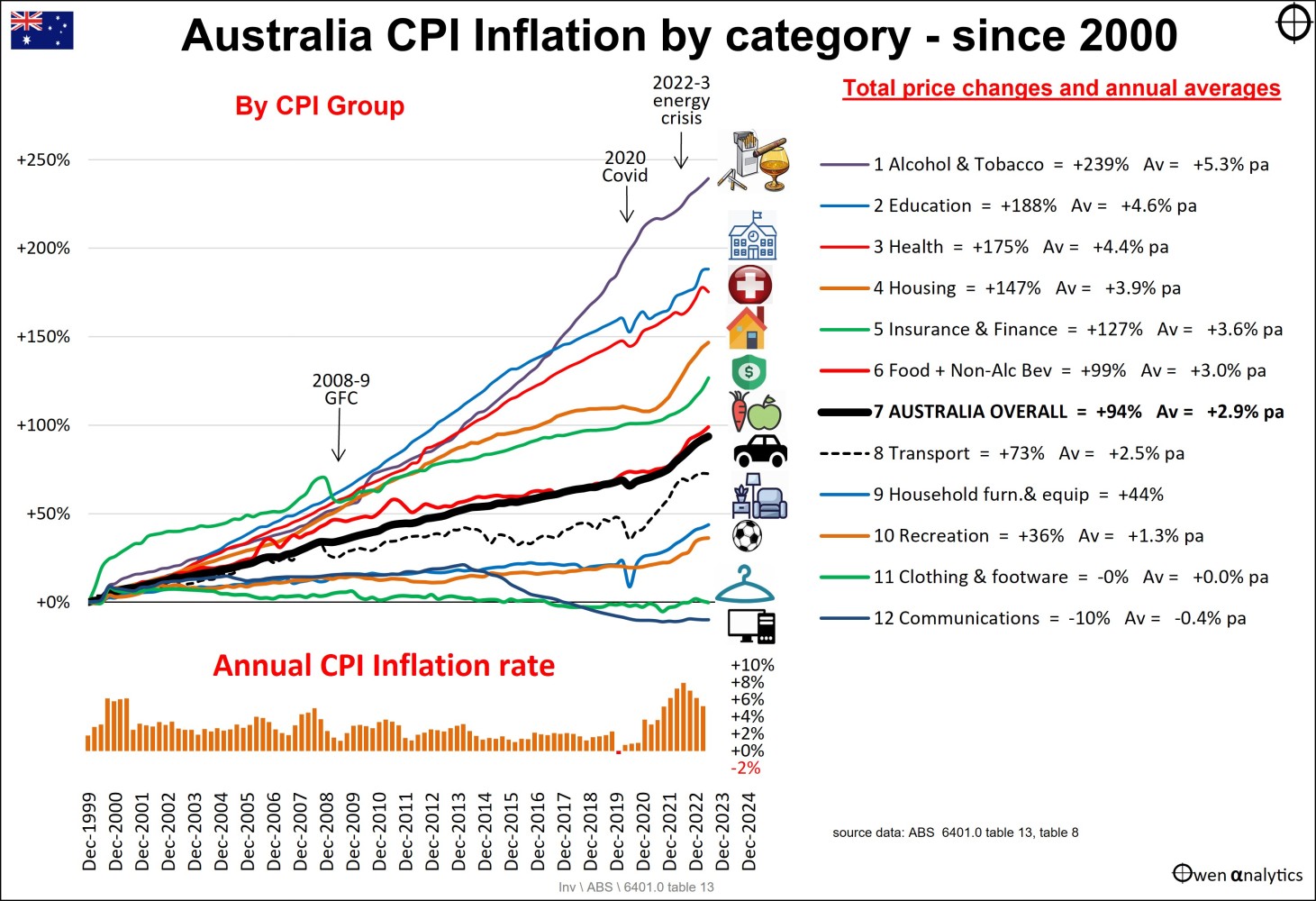

Different inflation rates for different types of spending items

This chart shows average inflation rates for different categories of spending since 2000. Price inflation for different types of spending items vary greatly.

Inflation rates for different categories of spending

At one extreme, alcohol and tobacco prices have more than doubled in price (with average inflation rate twice that of CPI) over the period. Most of the price increases are taxes. Governments love taxing alcohol and tobacco because they know people will keep buying them regardless of price.

At the other extreme, computers, phones, and other tech gadgets have actually fallen in price (i.e., negative inflation).

Broadly, prices of items with a large Australian labor content (e.g., healthcare, education, household repairs, power, water, gas) are rising at much higher rates than ‘CPI,’ while items imported from low wage countries have actually become cheaper or stayed flat (clothing, footwear, computers, phones, appliances, cars).

Cheap foreign labor keeps prices of imports low

Therefore, people who spend more than average on items imported from low wage countries – e.g., electronic gadgets, cars, clothes, and household items - are going to have personal inflation rates that are lower than CPI.

Conversely, people who spend more than average on services with high local labor content - healthcare, education, insurance, finance, housing, and household utilities – are going to have personal inflation rates that are higher than the official ‘CPI’ inflation.

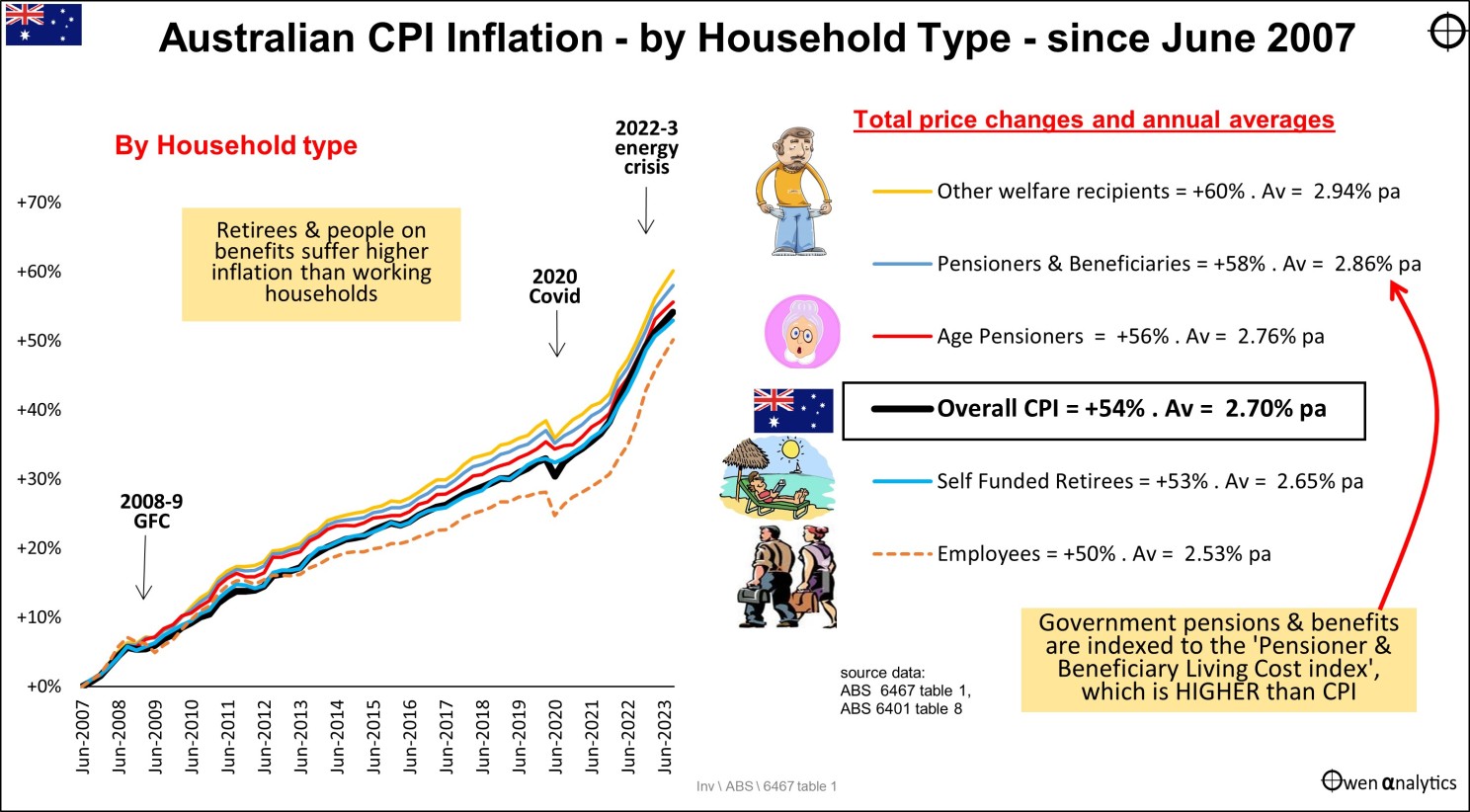

Different inflation rates for different household types

The next chart shows inflation rates in Australia since 2007 for different types of households.

Overall CPI inflation has averaged 2.7% per year over the period, but employed households experience lower inflation, while aged pensioners face higher inflation.

Inflation rates for different household types

Workers have lower inflation

Working households spend more of their budget on goods (most of which is imported from low wage countries, like clothing, appliances, furniture, equipment, cars), so their inflation rate is lower than CPI.

They may complain about high interest rates and high house prices, but they are ‘asset poor but income rich,’ and their inflation rates are lower than CPI.

Age Pensioners

Pensioners, on the other hand, are generally ‘asset rich but income poor.’ Pensioners spend more of their budget on items with high Australian labor content (services, like health care, household utilities, insurance), so their overall inflation rates are higher than CPI.

Fortunately, government welfare payments, including the aged pension, are indexed at the ‘Pensioner and Beneficiary Living Cost Index’ (PBLCI), or CPI, whichever is greater. The PBLCI is generally higher than CPI inflation, so aged pensioners are covered.

Australia has a great system whereby, if everything else fails, you can still fall back on the age pension, which is indexed for life at the welfare recipient inflation rate, not just CPI inflation.

Self-funded retirees

Self-funded retirees, in aggregate experience, price inflation rates a fraction lower than CPI – because they have higher incomes than aged pensioners, so high labor cost items (healthcare, household utilities, household repairs) make up a lower proportion of their total income than is the case for pensioners, and they probably also have more to spend more on imported goods.

Other welfare recipients

Recipients of welfare other than the aged pension (i.e., unemployed, carers, disabled), suffer not only the lowest incomes but the highest inflation rate, as most of their income goes on essentials.

Small differences compound over time

These differences in annual inflation rates may seem small, but the power of compounding magnifies even small differences into very large differences in living standards over long periods, like 30 years of retirement.

How does all of this relate to investment and retirement planning?

‘Inflation’ indexing only protects CPI inflation, not your personal inflation

‘Inflation-indexed’ bonds and retirement products like ‘inflation-indexed’ annuities, are generally indexed to CPI inflation, but is that going to be enough to cover your own ‘personal inflation rate’?

If your expenses inflation rate is higher than CPI, then you will need more investment capital per dollar of spending. Put another way, you can afford to spend less of your capital each year if you want to keep the balance growing in future to cover your expense inflation and preserve your purchasing power.

The problem with ‘CPI+’ portfolios

Most long-term pension/retirement funds target long term returns at a specified margin above inflation. For example, your investment strategy might target an ‘inflation-adjusted’ (or ‘CPI+’) return of say ‘CPI+4%.’

This means the portfolio asset allocation is designed so that if 4% of the balance is withdrawn each year, the balance (after withdrawals), and future withdrawals, are designed to keep growing for CPI inflation, to preserve the real purchasing power of the fund and also the purchasing power of future withdrawals.

That is fine if your expense budget is rising at the same rate as CPI inflation, but what if your own personal inflation rate, based on your own spending pattern, is higher than CPI inflation?

If your own personal inflation rate is more than CPI, then a ‘CPI+4%’ portfolio is not going to preserve its real value of withdrawals and the portfolio balance after withdrawals.

If you want to maintain the real purchasing power of withdrawals and the balance after withdrawals, then the three main options are:

- increase your investment income by chasing higher returns (take on more risk and volatility),

- accept the need to ‘eat to capital’, (or more than you planned to)

- lower your spending budget.

(Note that the government’s mandatory ‘minimum withdrawals rates’ for Super accounts in Pension phase start at 4% for people under 65, then rise to 5% for 65-74 year olds, 6% for 75-79 year olds, etc. The Super rules are designed to run down Super (‘eat into capital’) and spend it, rather than pass it on to the next generation.)

Spending patterns change over time, and people are living longer

This process is complicated by two further factors.

The first is that spending patterns change over time, and this will change your personal inflation rate. Generally, as people age, they tend to spend less on imported goods and more on services that have higher inflation rates, like healthcare. This will generally increase their personal inflation rates over time.

The second is that people are living longer, due to improvements in medical treatments and nutrition. These additional years magnify the negative impact of compounding on even very small differences in inflation rates and returns over time.

Hopefully, this article will assist in discussions with investors and their advisers - in assessing their own ‘personal inflation rate’, whether they have the right long-term retirement portfolio strategy given their personal inflation rate, income needs, risk tolerance, and whether it is consistent with their views on the balance between spending it versus preserving it for the next generation.

See also: Australia -v- Rest of the world on inflation and interest rates

Monthly Market Monitor - Sep 2023 - Reality sets in - higher inflation & interest rates

Thank you for your time – please send me feedback and/or ideas for future editions.

‘Till next time – happy investing!