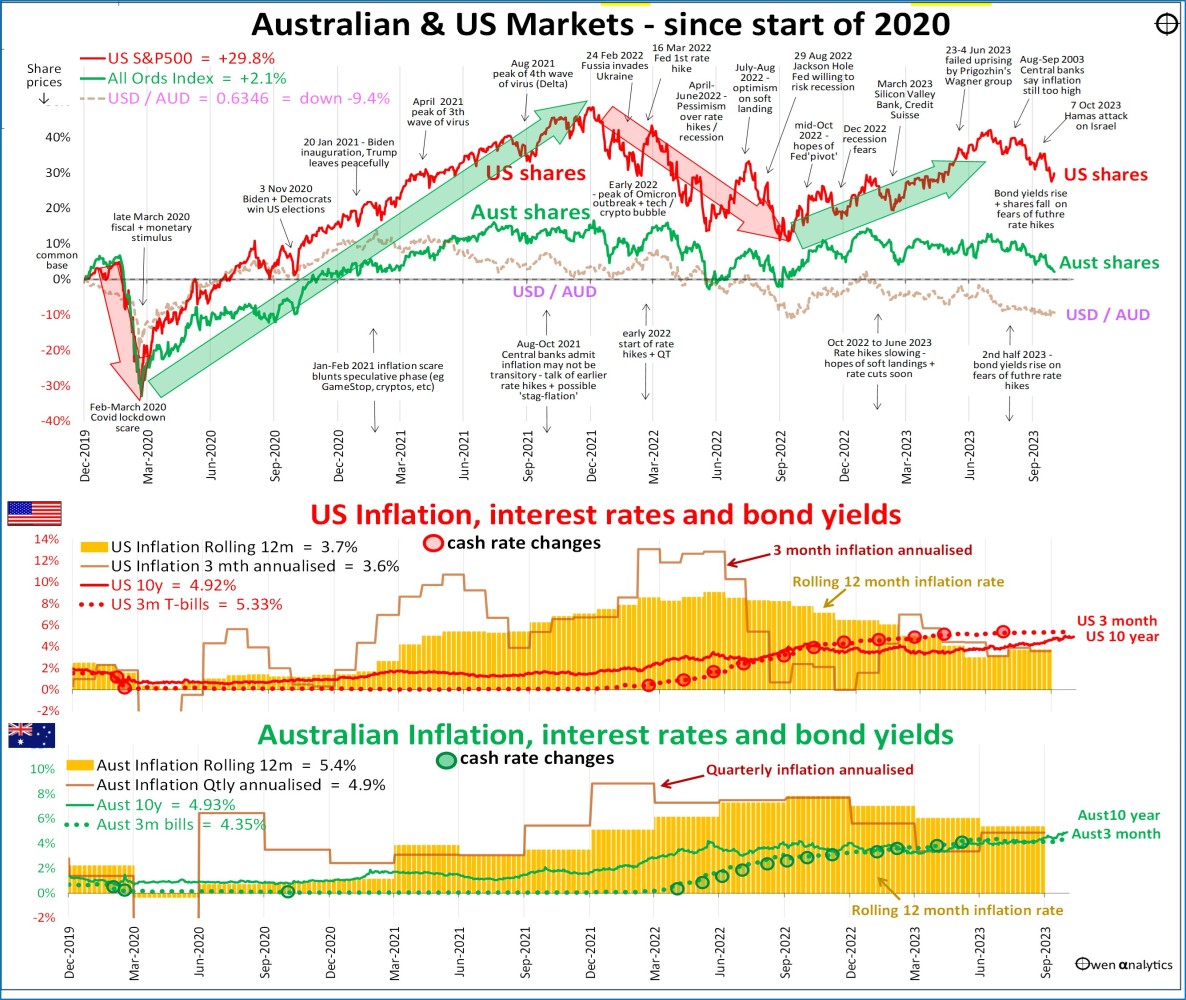

Welcome to the Monthly Market Monitor for October 2023. First, here is our quick snapshot of Australian and US share markets, short- and long-term interest rates, inflation, and the AUD since the start of 2020:

Australian and US markets - shares, inflation, bond yields, cash rates

The upper section shows US shares (red) doing much better than Australia (green), because the US is home to the global tech / online giants.

Also in the upper section is the USD / AUD exchange rate, which also follows share market cycles.

Inflation and interest rates

Below the main chart are inflation and interest rates in the US and Australian markets. The orange bars are rolling 12-month inflation rates, which are the ‘headline’ annual rates quoted most often in the media.

These show that annual inflation peaked in the middle of 2022 in the US and at the end of 2022 in Australia. The RBA’s rate hikes have been later and lower than the US Fed. However, inflation in both markets, and around the world, has been falling in 2023.

A better measure of the current trend, direction, and 'running rate' of inflation is the annualized three-month inflation rate (maroon lines in both lower charts). The 'running rate' of inflation is now lower than its peaks in both markets, but not low enough yet to bring inflation down to target.

See also - Australia -v- Rest of the world on inflation and interest rates

Other developments in October

Aside from central bankers warning of the possible need for further rate hikes, and warning against inflationary government spending sprees, other key developments during the month included the following:

- Share markets and bond markets posted negative returns once again as bond yields rose with fears of further rate hikes needed. More details later in this report.

- Commercial property – more cuts to prices & valuations, more funds defaulting, freezing redemptions.

- Australian Housing – price rises and buyer confidence appear to be slowing with expectation the RBA is not done yet with rate hikes.

- Debt stress – the much heralded ‘mortgage cliff’ has not yet resulted in a major outbreak of widespread foreclosures, but the stores of spare cash from the Covid stimulus handouts are being run down.

- China – widening of the property/construction/finance collapse. Some minor support measures from Beijing, but no massive stimulus boost like 2009 or 2016.

Commodities – lower prices for oil, coal, industrial and battery metals. Weak demand + strong supply. Gold higher. Further details later in this report.

- Aussie dollar – lower again, with lower share prices, as per the usual pattern. More details later in this report.

Tensions in the middle east rose dramatically with the 7 October Hamas attack on Israel, and Israel’s subsequent invasion of Gaza. Global tensions also accelerated on 17 October when Xi Jinping backed is his ‘dear friend’ Putin.

- US House or Reps Speaker stand-off chaos was finally resolved with the election of right wing, pro-Trump Republican, Mike Johnson as House Speaker on 26 October. He must now negotiate with the Senate to avoid another embarrassing government shutdown before the money is due to run out on 17th November.

- US economic growth remains relatively strong.

Share markets

Global share markets overall were down by another -3% in October, after similar falls in September and August. Most markets are more or less back to where they were in early-mid 2021.

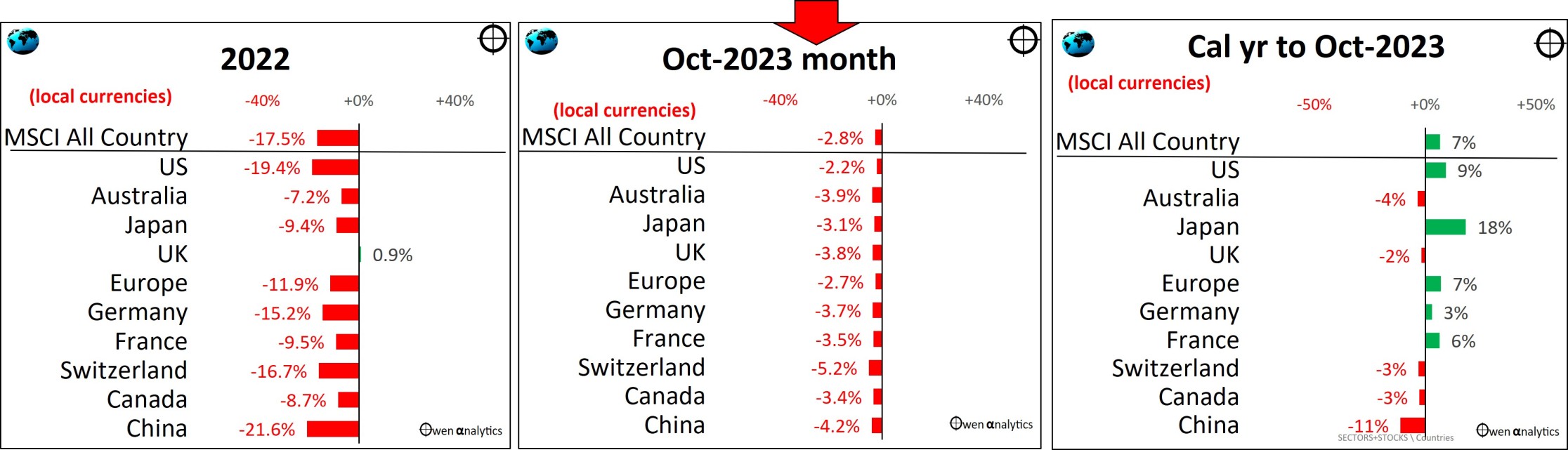

Countries

All major share markets lost ground again in October, the third month of declines. The consistency of the falls across the board is a sign that prices are being driven more by sentiment the fundamentals, which vary widely between markets.

share markets by country - 2022, October 2023 and 2023 year to date

Rare exceptions to the global slide in October include: Denmark (Novo Nordisk up strongly again with its Ozempic diabetes/weight loss drug in the current GRP-1 frenzy); and Poland (mainly Orlen, fossil fuel producer).

Year to date (right chart above), most major markets are still ahead. Australia, UK, and Canada are lower because of their heavily reliance on miners and banks. China is also well down, for a host of reasons.

The modest gains so far this year on world markets are still well short of recovering the losses in 2022 (aggressive rate hikes). The UK was the only market to survive the 2022 sell-off because fossil fuels was the only sector to rise in 2022 (next charts).

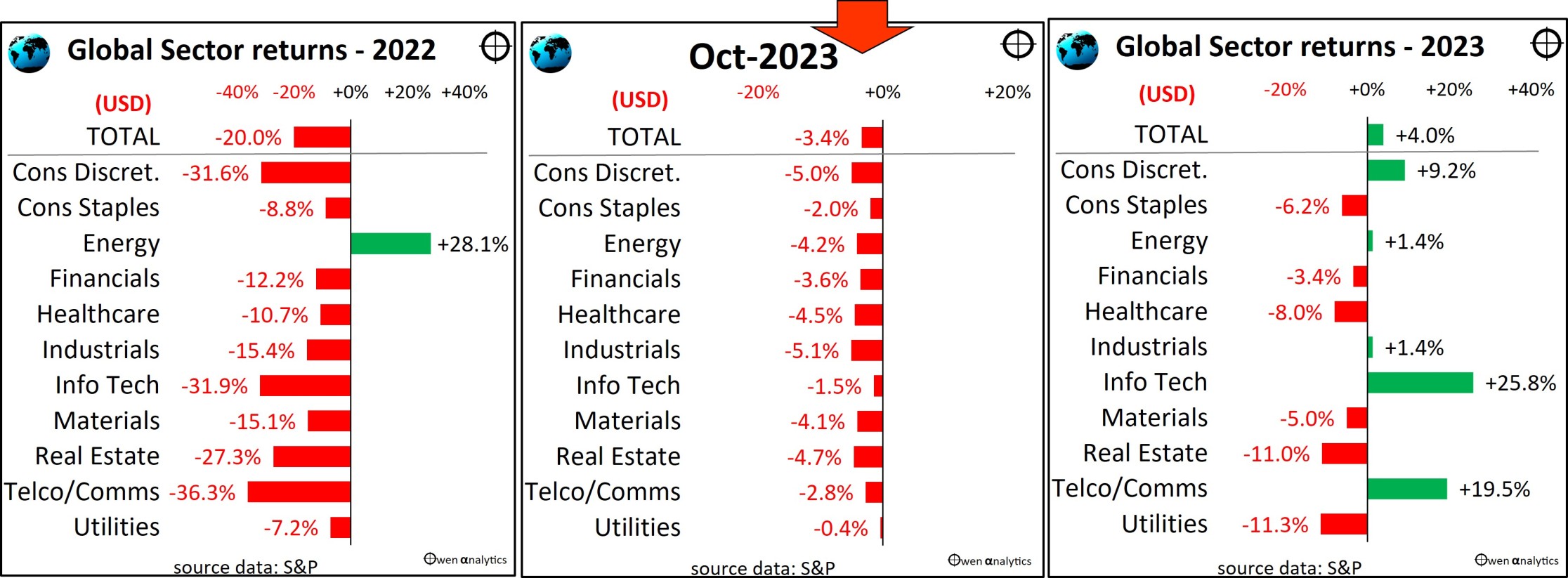

Sectors

Every industry sector was down across the board in October, for the first time since February, when the same fears were in play then as now - sticky inflation and further rate hikes.

global share market returns by sector

global share market returns by sector

Rising fuel prices kept inflation rates (and interest rates) elevated, which has weighed on global markets over the past three months.

Year to date (right chart above), the US tech/online/A.I. giants are spread across three sectors:

- ‘Discretionary’ (Amazon, Tesla),

- ‘Tech’ (Apple, Microsoft, Nvidia, Adobe), and

- ‘Comms’ sector (Meta/Facebook, Alphabet/Google, Netflix).

The other sectors (aside from fossil fuels) are still well below their highs at the start of 2022.

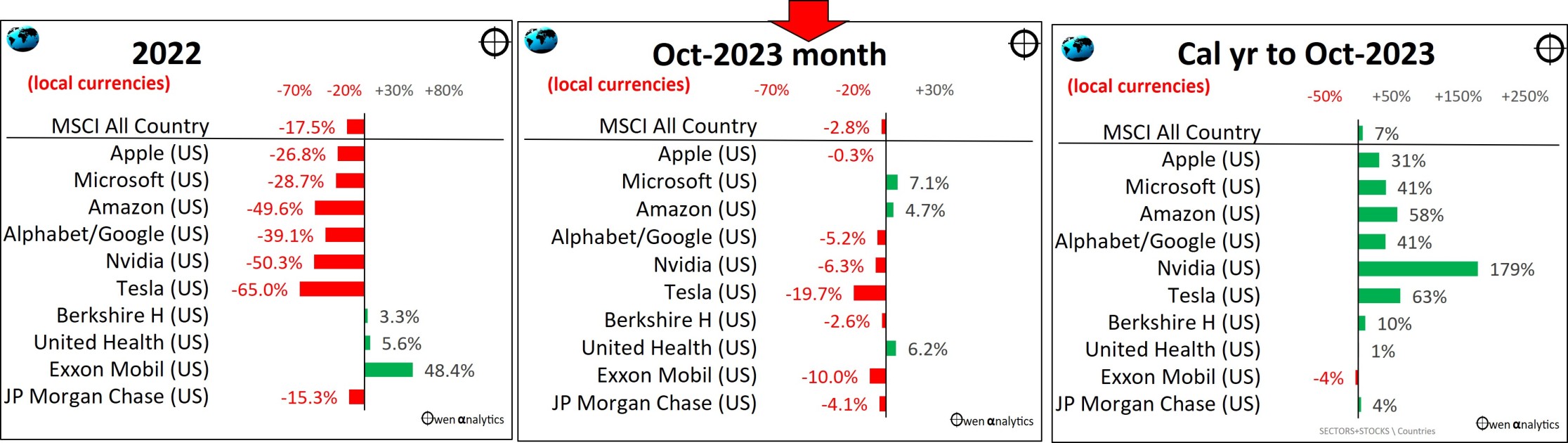

Global Stocks

US companies dominate the list of the world’s largest listed companies (former Chinese stars Alibaba and Tencent are long gone from the top 10 list).

In October (middle chart), Microsoft, Apple, and United Health were stronger, but the rest were weaker:

top 10 global stocks

top 10 global stocks

Tesla was worst, down -20% to $200, where it was three years ago. Slow global EV demand hit sales, margins, and profits.

Year to date the big winners are still the US tech giants, but all except Nvidia (the A.I. 'hot' stock) are yet to recover their 2022 price declines.

See also - Where are we now? – US Profits: Recession or Rebound?

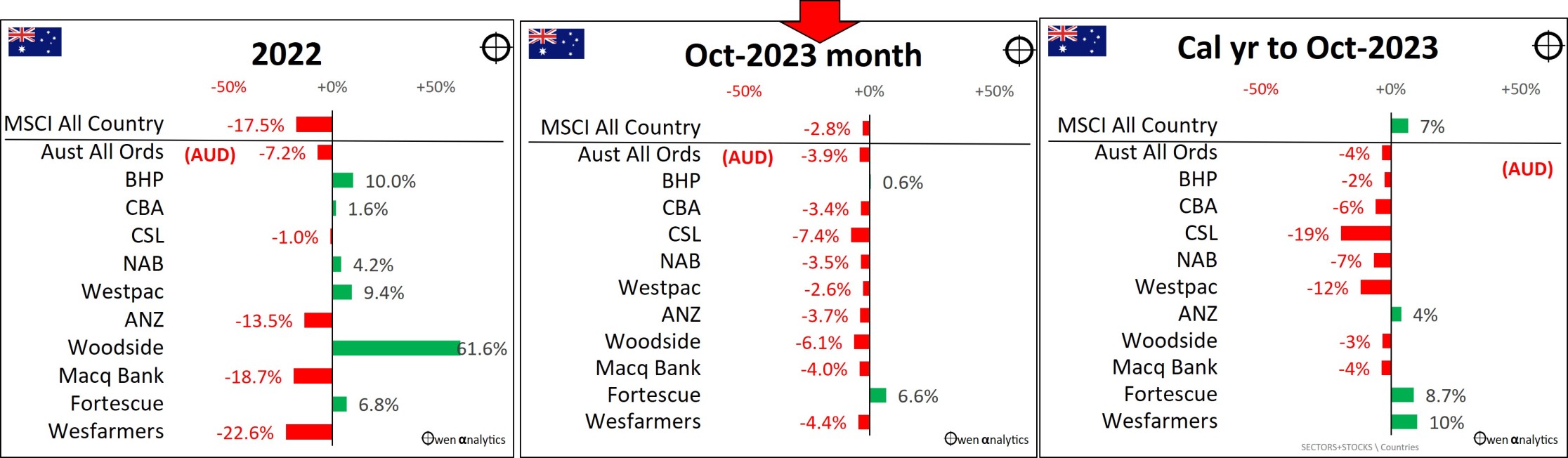

Australia

The local share market here was also weaker virtually across the board in October (except iron ore producers, as iron ore prices held up flat after recent gains).

top 10 ASX stocks

top 10 ASX stocks

The All Ordinaries ended the month at 6,947. This is 12% below the post-Covid peak on 4 January 2022 before the 2022 rate hike sell-off, but still 5% above the 20 June 2022 low.

Year to date (right chart), the overall market is being dragged down by the banks and CSL, which has had some profit downgrades and also problems with its Vifor acquisition, and GLP-1 fears. CSL was one of the great ASX success stories from 1994 float until 2020, but it has always been expensive (relative to fundamentals and relative to global peers).

See: Case Study: Case Study – CSL: growth superstar at a rare bargain, or over-priced mature low-growth behemoth?

In 2022 (left chart above), the Australian share market held up better than most other countries in the global sell-off, thanks mainly to our fossil fuel and iron ore producers, mainly Woodside and BHP. But Australia has been a global laggard this year.

So far this year, Wesfarmers has been the main standout, with its retailers (Bunnings, Kmart, Officeworks, and now Priceline) holding up relatively well despite rising interest rates and costs. Fortescue Metals is also ahead, with iron ore prices holding up, and its new high-grade Iron Bridge concentrate boosting the quality and prices of its otherwise low-grade ore.

For a full rundown of the most recent ASX reporting season – see ASX reporting season in 4 charts - $40b wiped off profits! - where did it go, and why?

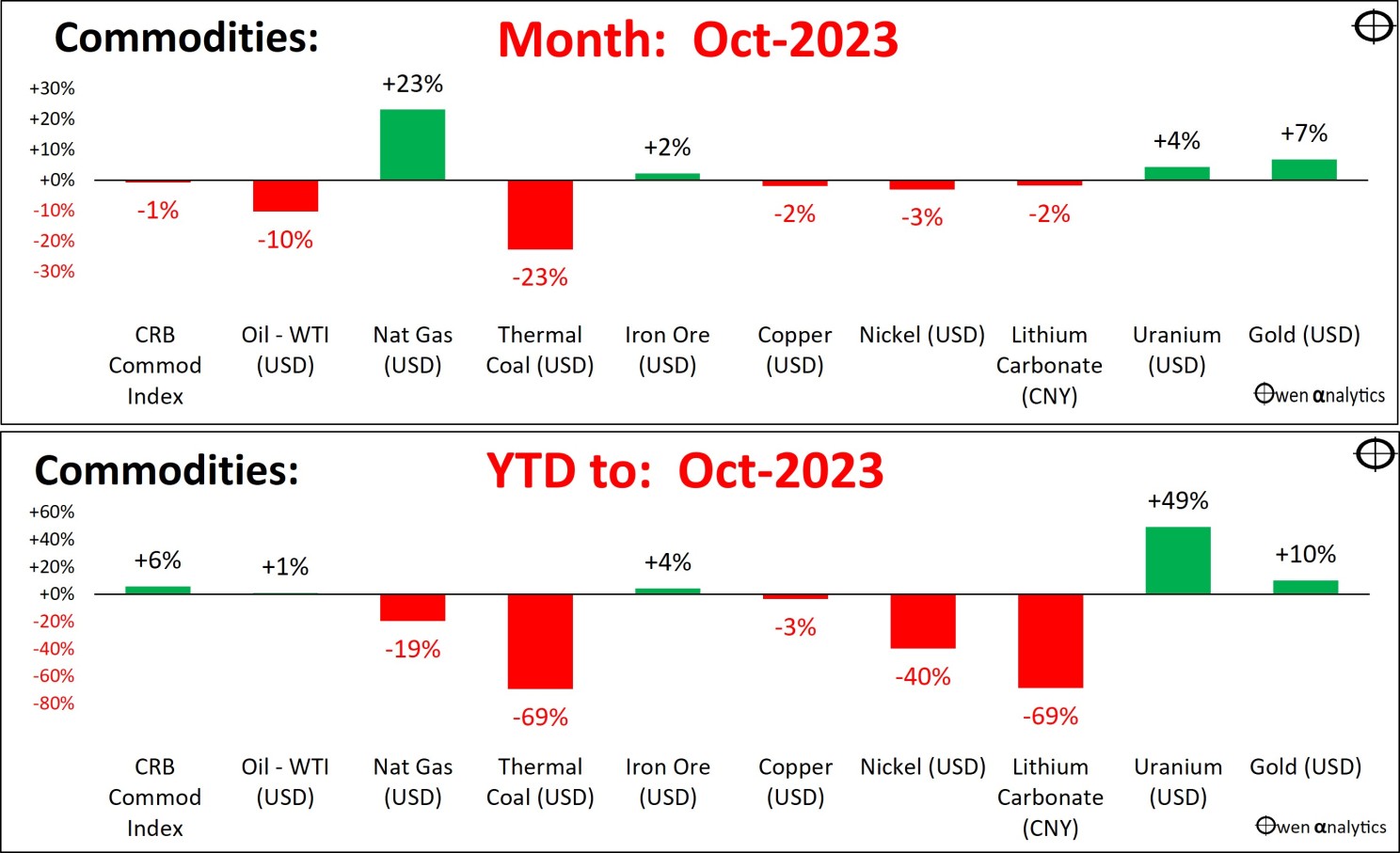

Commodities

On commodities markets, oil fell 10% in October. Oil prices rose briefly after the 7 October Hamas attack on Israel, but by the end of the month, prices were back lower than before the attack, with slowing Chinese and global demand.

Coal prices also fell on slowing demand. On the other hand, natural gas prices rose to a 9-month high, with strong demand expected in the up-coming North American winter.

Industrial and battery metals also fell with slowing demand for EVs, especially in China.

changes in key commodities prices - month and YTD

changes in key commodities prices - month and YTD

Year to date, most industrial commodities prices are down, with the global economic slowdown.

Battery metals have been weaker this year. On the demand side, EV sales have been weak globally, with rate hikes affecting spending. On the supply side, outlooks for higher production of lithium in particular have deflated the spectacular price lithium bubble. More on this below.

On some unique perspectives on Chinese demand for Australian rocks – see:

The BIG picture – China’s steel production – the ‘Sydney Harbour Bridge’ index

Chinese construction – the Sydney CBD index

Here is the cleaned HTML code: html Copy code

The standout this year has been uranium, as a likely solution to speeding up the transition from fossil fuels. We will look at the perils of trying to chase the uranium cycle in an upcoming report.

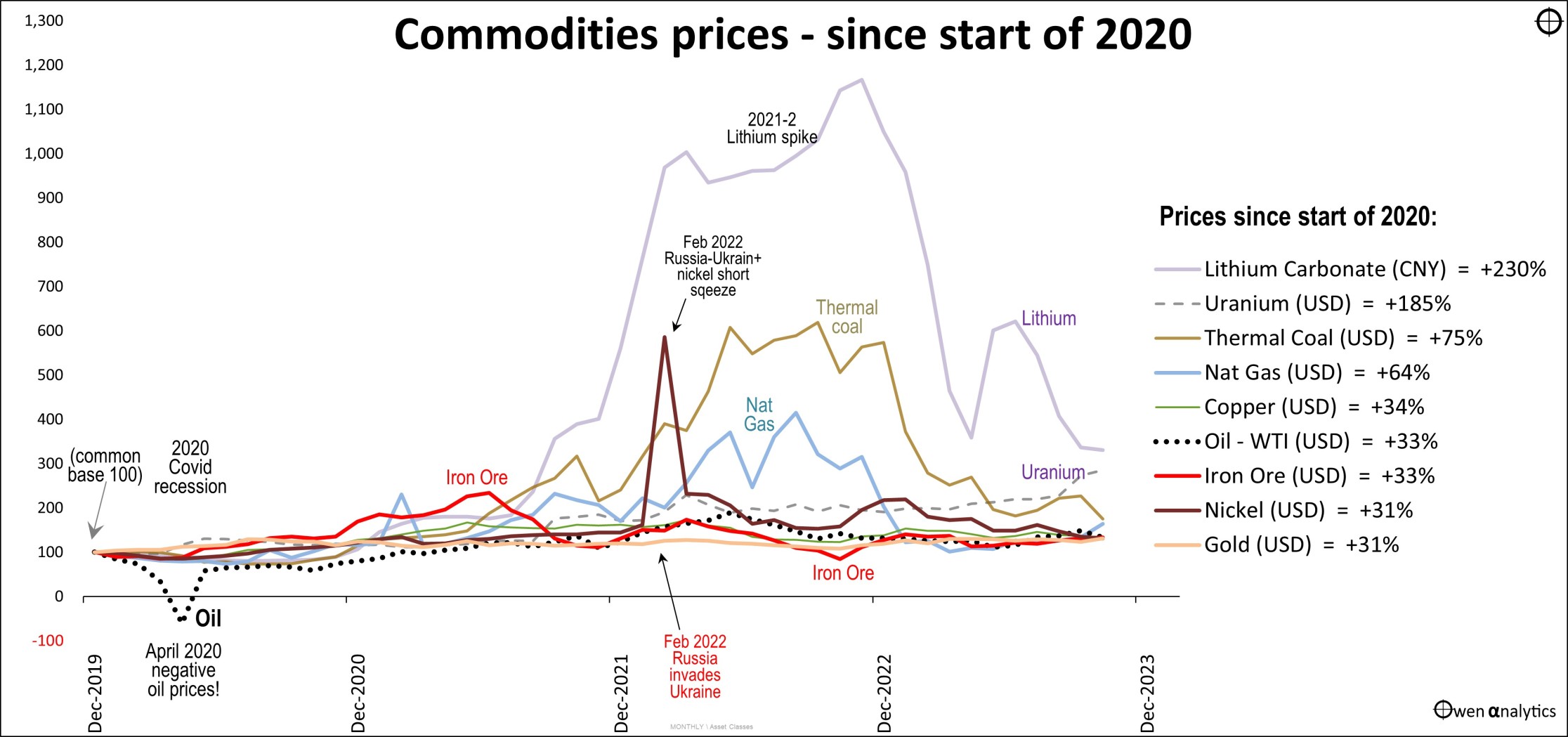

For a medium-term perspective, here are prices from a common base since the start of 2020:

This shows the boom-bust effects of the Covid lockdowns and Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Most investors focus on the demand side of the commodities equation – the demand for energy, demand for industrial metals, demand for electric vehicles, etc.

The problem is that almost all of the swings in commodities prices (and share prices of commodities-related stocks) are due to what happens on the supply side.

OPEC production wars sent oil price negative in 2020. Mine disasters in Brazil sent iron ore soaring in 2021. Covid port closures in South Africa and Russian sanctions in Europe sent coal soaring in 2021-2. Nickel prices soared after Indonesia banned exports, and a short squeeze following the Russian sanctions. Nationalisation of lithium mines in Mexico and Chile sent lithium prices through the roof.

Many investors saw rising prices as proof of their theory on strong demand, and jumped into anything and everything that had a hint of their chosen hot mineral. Explorers and producers saw prices rising and they accelerated their exploration and new mine development to try to cash in on the booming prices.

The result is always the same in every commodity boom – prices collapse when temporary supply restrictions are resolved, new supply comes on stream, and supply over-takes demand. Making things worse this time is weakening demand for electric vehicles in China.

Today, commodities prices are still well above what they were three years ago, but production volumes are much higher, and costs have soared. As with all forms of investment, timing is everything!

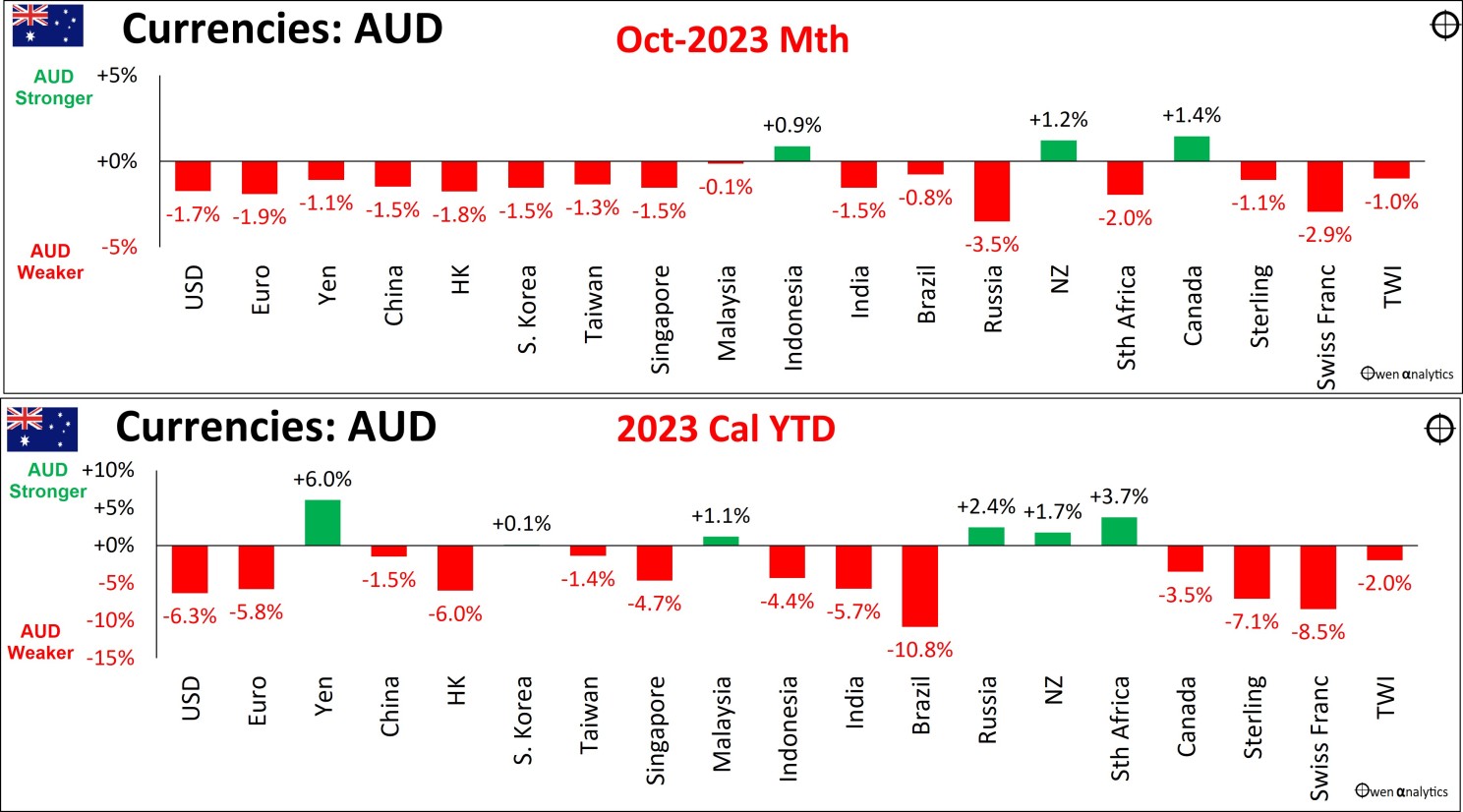

Currencies

In October the Aussie dollar fell against the USD for the third month in a row, as per the usual pattern when share markets fall. The AUD also fell against all other major currencies, including the Euro, Yen, RMB, and Pound, and -1.5% against the trade weighted index, despite the likelihood of the RBA hiking rates next week.

For the year to date, the AUD is down against all major currencies except the Yen, as Japan is the last country clinging on to QE and artificial suppression of interest rates and exchange rates.

Aside from the weak local share market, the main reason for the AUD slide this year has been the fact that interest rates have been 1% higher in the US than here, attracting money out of Australia and into the US.

This ‘interest rate differential’ is likely to continue for some time. Although inflation is higher here than in the US, the Fed looks more committed than the RBA to higher interest rates to control inflation. This should support the USD even if the US shares rally returns.

Bonds

October was another bad month for bond investors in Australia and the US, especially government bonds.

In Australia, yields rose across all maturities by 0.3% to 0.5%. Yields on US 10-year notes briefly hit 5%, ended the month a fraction below 5%, in line with Australian 10-year yields.

Why the sudden shift from shares into bonds?

During the past six months, we have watched from the sidelines as investors piled back into bonds because interest yields on bonds were finally higher than dividend yields on shares. That may be true, but it was just restoring what has almost always been the position throughout history.

The fact that bond yields are now higher than dividend yields is no reason to suddenly dump shares and pile into bonds. Bonds have no inflation hedge, shares do. Bonds have no upside potential, shares do. Bonds have no tax breaks, shares do.

Investors who shifted from shares to bonds must have assumed that bond yields would not rise further, or would actually fall back. That would only occur if inflation magically fell back to target levels without further rate hikes, and/or we have a deep recession.

Neither is the case. Inflation remains above target, jobs markets are very tight, wages are rising, economic growth remains remarkably strong, governments are continuing to fuel inflation with their wild spending sprees, and central bankers are warning they are not done yet with rate hikes.

If we do get deep recessions, government bond yields would fall temporarily and bonds would post good returns temporarily. But those bond price gains in recessions are quickly reversed and turn into price falls on the way out as economic outlooks pick up, usually in the middle of recessions. Buying bonds as a short- term recession hedge requires superb short-term timing and discipline.

On the other hand, if they are buying for the medium or long term, they are going to be hurt as well.

The ‘normal’ or ‘neutral’ level for cash rates in the US and Australia is around 5% or so (we have covered the reasons in prior reports). The US is already there, but might need to go higher first to bring down inflation. Australian cash rates are still below ‘neutral’.

In the medium to long term, yields on long term bonds will need to be another 1.5% higher than ‘neutral’ cash rates, as a ‘term premium’ above cash. (The ‘term premium’ is the additional yield required to compensate for locking up your money for years).

Therefore, in the medium- to long-term, yields on long term government bonds in Australia and the US are probably heading back up to around 6% or more. Why would I buy them now if the yield is less than that? I’m only going to suffer capital losses as yields rise.

Even with yields now at 5%, if I hold the bonds to maturity, sure I receive the 5% yield to maturity, but I lose on the ‘opportunity cost’ of being locked in at the current yield instead of higher yielding bonds as yields rise on the way back to ‘normal’.

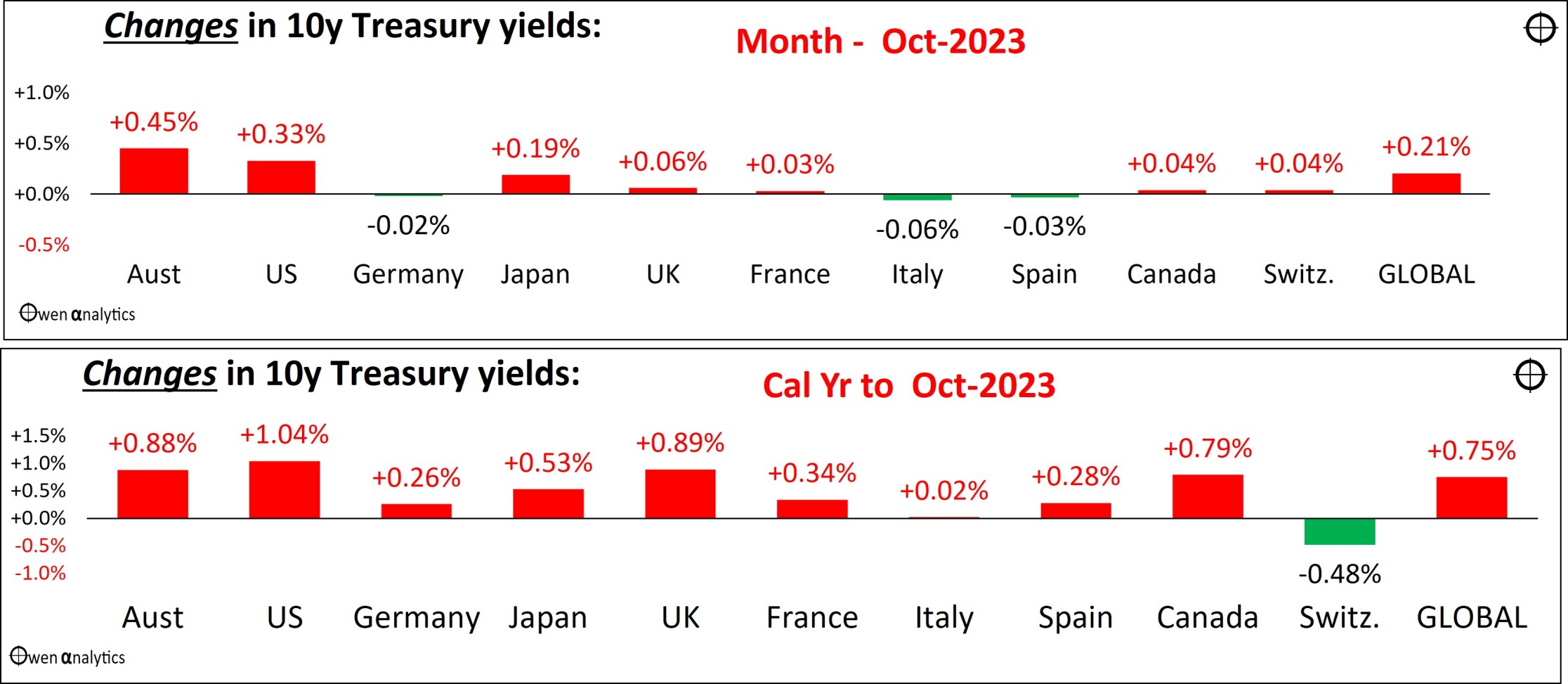

The realisation that inflation and interest rates are likely to be higher for longer sent bond yields rising again in October, especially in Australia and the US, but even in Japan:

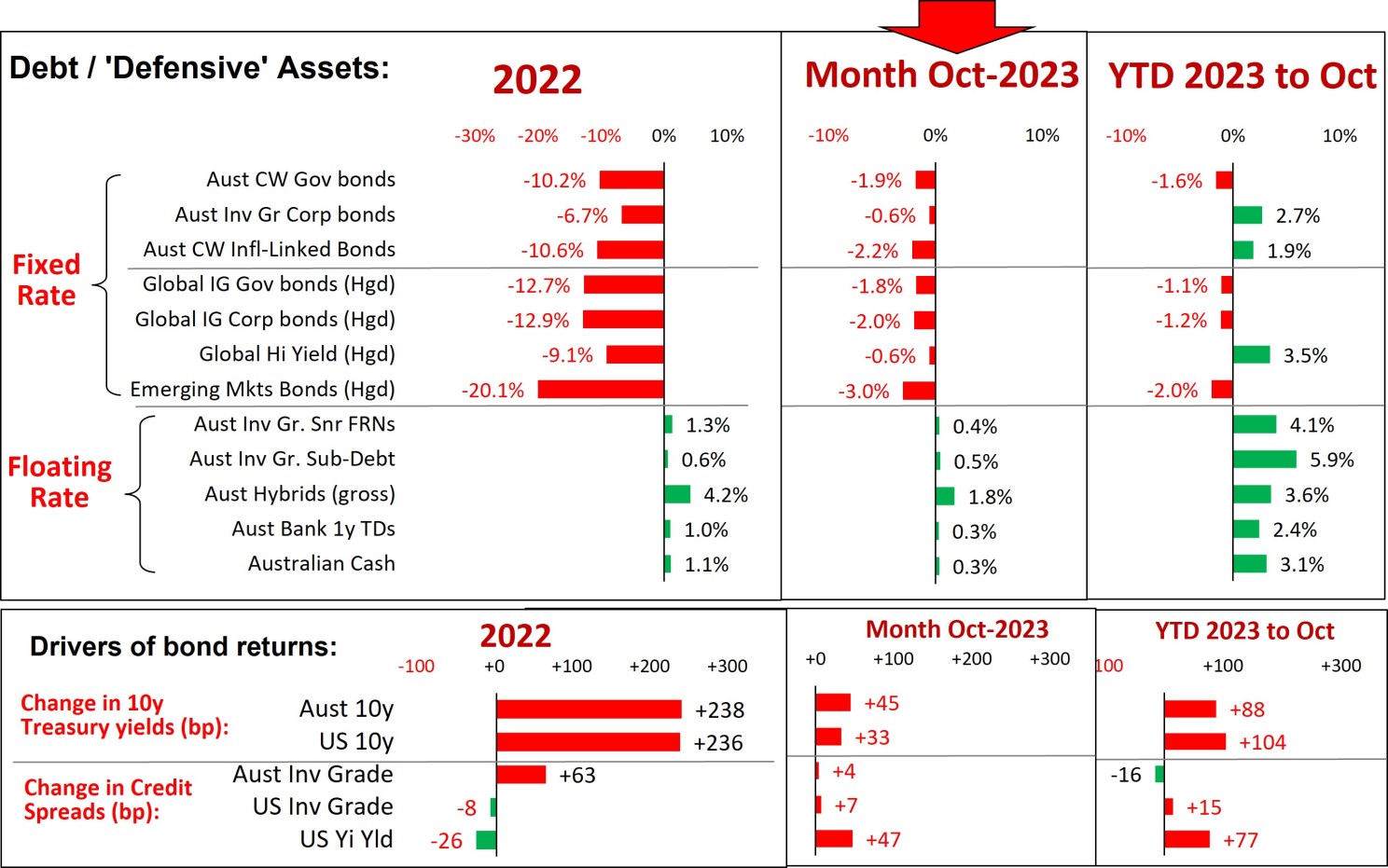

As a result, October was another bad month for fixed rate bond returns. Here are total returns (income plus unrealised capital gains/losses) for the main bond markets.

The lower charts show the main drivers of bond returns: changes in treasury yields and changes in credit spreads.

The rising treasury yields and negative bond returns in 2023 are not nearly as bad as in 2022, which was the worst year for government bonds in a century.

Floating rate

In the lower half of the top chart above are the main ‘floating rate’ markets for Australian investors. Interest rates on floating rate securities rise and fall with cash rates, so returns have been rising with the cash rate hikes since early 2022, which have hit bond returns badly.

We have heavily favoured floating rate over fixed rate for the past couple of years for this reason.

Stay tuned for more fact-based analysis and insights for long-term investors.

Next stop: Uranium!

With the lithium bubble bursting and uranium prices on the rise, my inbox is now full of questions from readers (and spam emails from hot stock tip-sheets) about how to jump on the next bandwagon - uranium.

(Surprise, surprise! - punters and spruikers never change!).

I cover some lessons from the last uranium bubble and bust my next story.

‘Till next time – happy investing!