The RBA is copping a lot of political heat from the PM, Treasurer, and other government ministers for not cutting interest rates like many other central banks around the world. Treasurer, Smiling Jim Charmer has accused the RBA of ‘smashing the economy’, and even former Labor Treasurers and ministers have piled on with even more extreme rhetoric.

Many countries in the ‘developed’ world are already into their second rate cut – like Canada, UK, Europe, and even New Zealand. The US Fed is likely to cut rates at its meeting this week. Why isn’t the RBA cutting rates any time soon?

The simple answer is that there is no need to cut rates. Here are five reasons:

-

-

- Cash rates are not ‘high’ – relative to inflation, or relative to historical average rates in Australia,

- The RBA rate hikes were later, slower, and lower than the rest of the world,

- so inflation in Australia is still above target (despite Australia having the highest inflation target in the world).

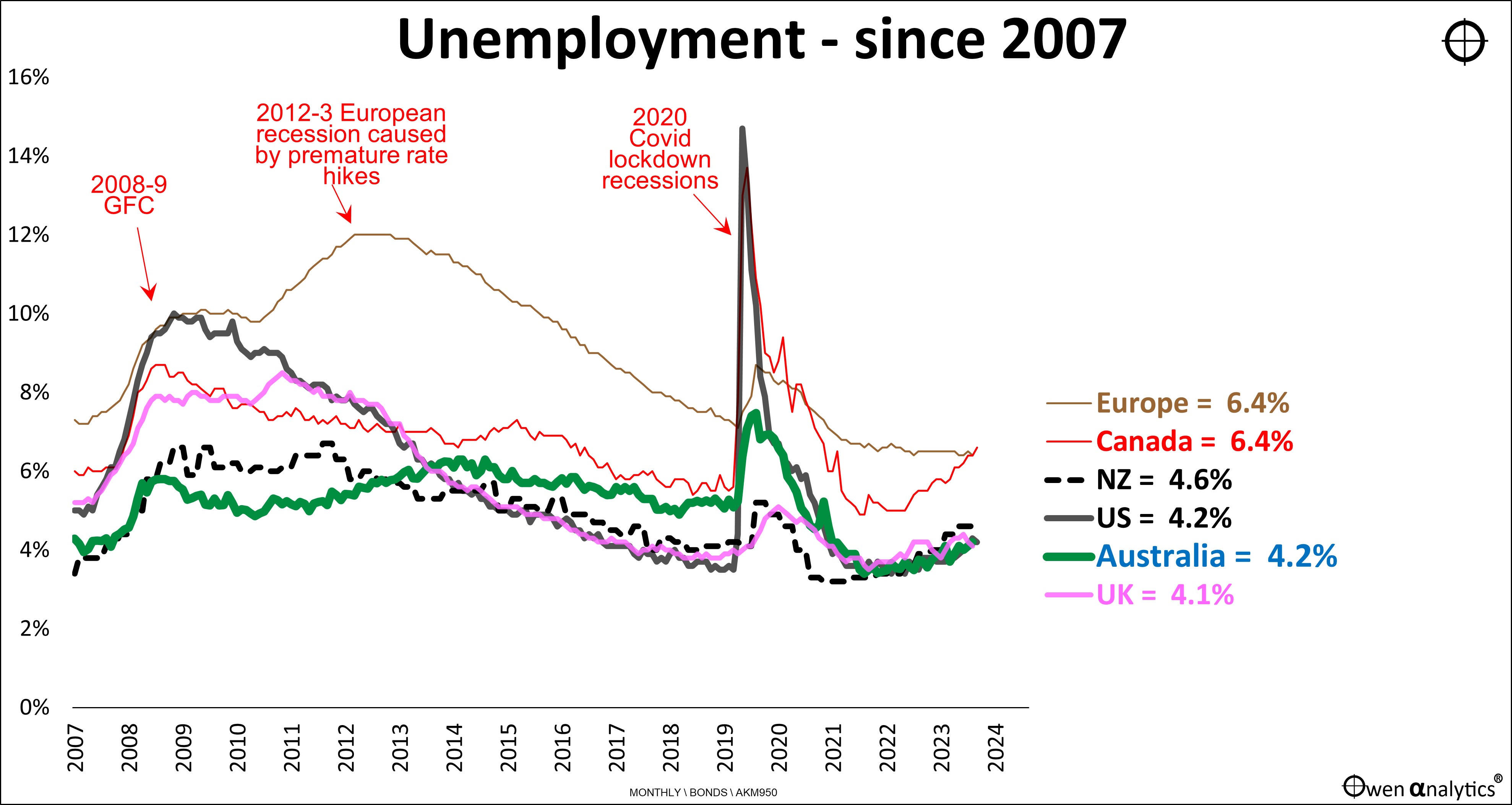

- There is no need to stimulate jobs, as unemployment is not high. We have near full employment, evidenced by strong wages growth.

- Nor is there a need to stimulate demand/spending, as the economy is already operating above full capacity – ie aggregate demand (spending) is greater than aggregate supply (capacity), putting upward pressure on prices.

These are all facts, not opinions.

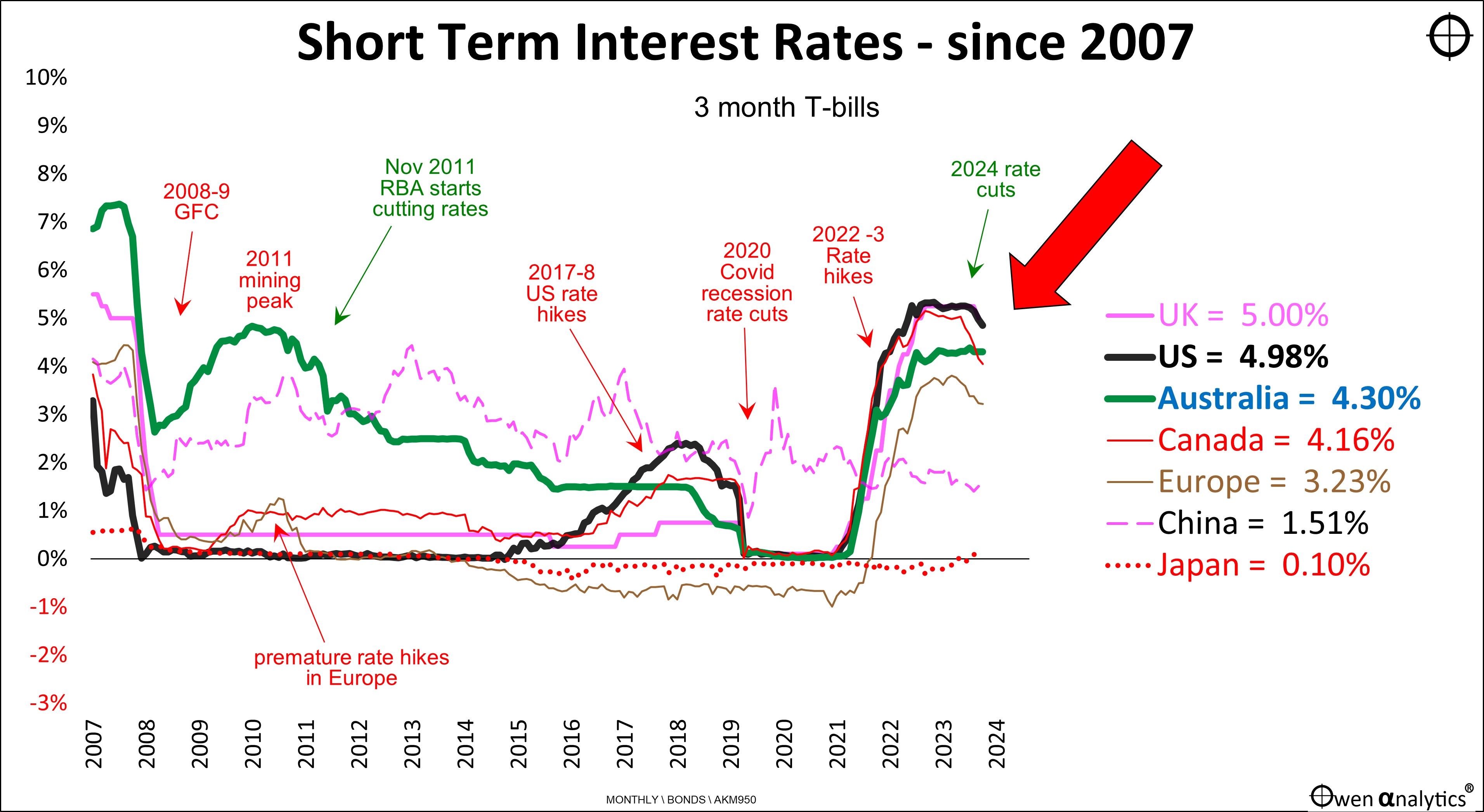

The first chart shows Australian short-term interest rates (green) relative to other major markets:

Nobody accused the RBA of ‘smashing the economy’ when cash rates were 4.75% in 2010-1 (when inflation was 3.5% as it is now), or when cash rates were 7.25% in 2008 (when inflation was 4.5%).

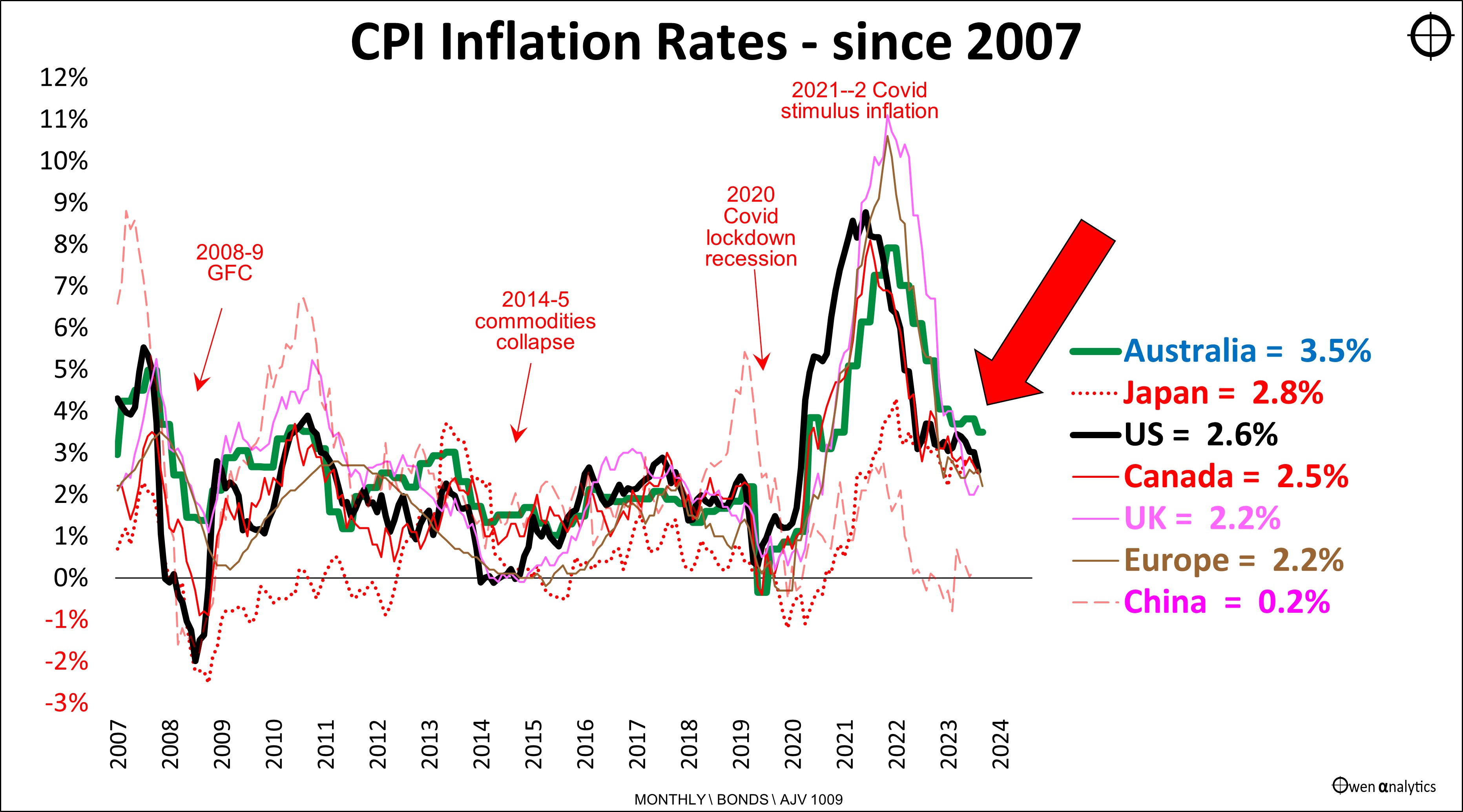

The second chart is the CPI inflation picture, with Australia still running higher inflation than other markets:

Inflation (whether measured by annual CPI, annualised 3-month CPI, ‘core’, ‘trimmed mean’, or any other measure) is higher in Australia for a few reasons:

-

-

- The RBA rate hikes were later, slower, and lower than the rest of the world, in attacking inflation. The RBA shot itself in the foot at the starting line in 2021 by forecasting inflation and interest rates would not rise for at least three years. By the time the RBA woke up to this monumental error of judgement, the inflation cat was well out of the bag.

- We have ‘stickier’ inflation – partly due to our entrenched centralised wages system (Keynes specifically identified Australia’s centralised wage system as a problem in his ‘General Theory’*). Australian inflation has averaged 1% higher than US inflation over the past century.

- Fiscal policy (government spending) is rising rapidly - at federal and state levels.

(* Keynes, ‘General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money’, London, Macmillan, 1936. pp. 267-9 in my 1973 edition)

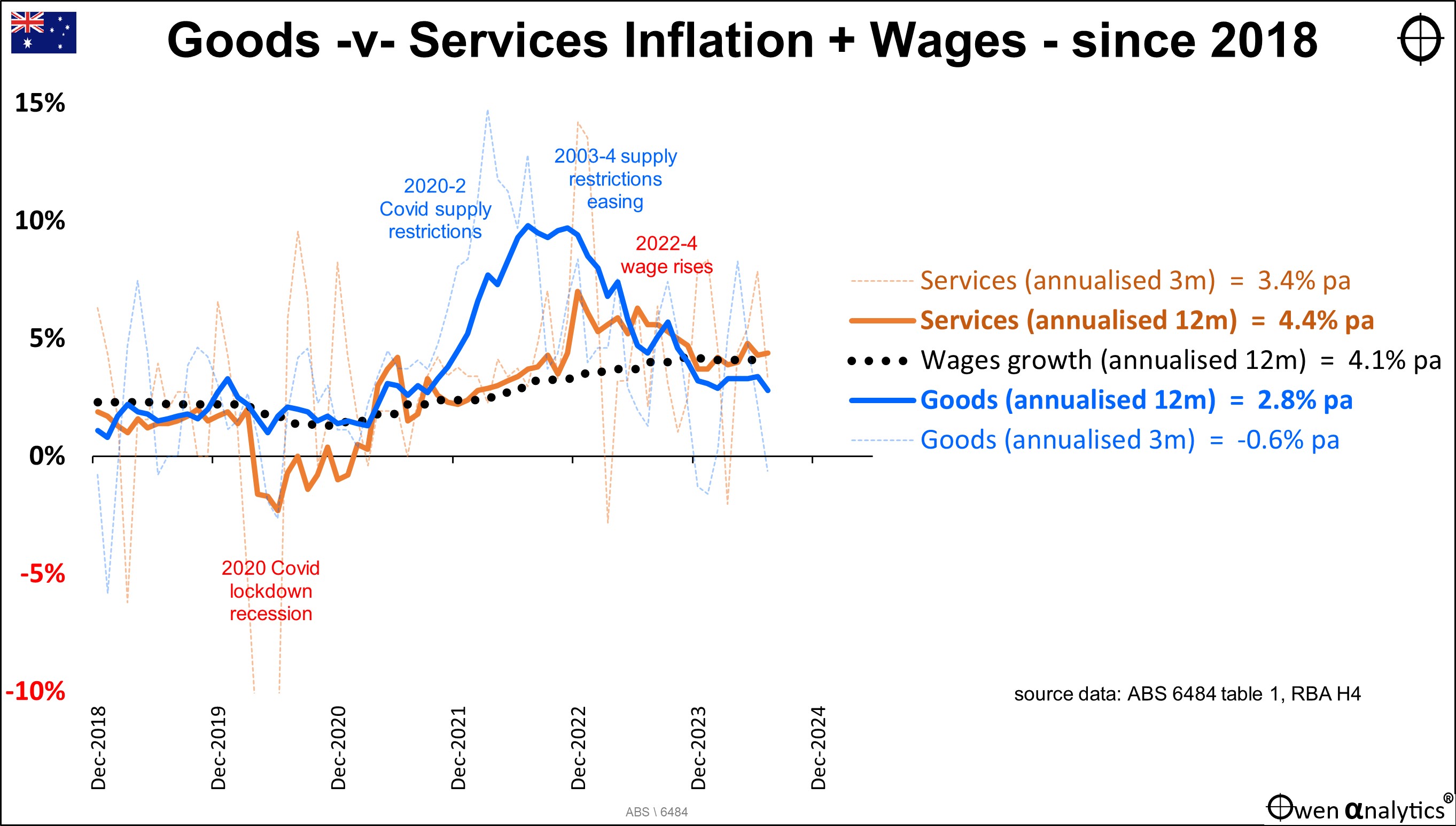

Goods -v- Services inflation

The problem is mainly with services inflation, being kept high by rising wages.

The third chart below is an update on the Australian picture for Goods inflation (blue) versus Services inflation (orange), and Wage inflation (black dots).

The solid blue and orange lines are rolling 12-month inflation rates, and the faint dotted blue and orange lines are annualised rolling 3-month rates, which show the recent trends, but are much more volatile.

Before the Covid lockdowns, goods inflation and services inflation in Australia were both running steady at around 2% pa – nicely within the target range. Then the Covid lockdown restrictions in 2020 hit global supply chains, sending goods inflation (blue) soaring above 10% during 2021-2.

As supply chain restrictions eased over the past couple of years, goods inflation declined, but still remains at 2.8%, toward the top end of the 2-3% target range for overall inflation.

Services inflation (orange) was sharply negative during Covid in 2020, then recovered in 2021-2, but is now running at a rather high 4.4%, due largely to rising wages.

Wages inflation (black dots) was running at around 1.5% to 2.5% pa pre-Covid, but rose to 3.3% in 2002, then steadily rising above 4% in the past two years.

Services inflation is likely to remain high if jobs markets remain tight and governments and employers allow unions to win wage cases purely to chase rising living costs with no requirement for productivity gains.

Unemployment

The final chart shows that Australia’s unemployment rate is still relatively low – relative to recent history here, and relative to other countries:

There is simply no need to stimulate jobs growth with rate cuts when strong jobs markets and wages growth are lifting prices and inflation.

When will the RBA cut interest rates?

It seems that investors, economists, and media commentators everywhere are almost universally calling for rate cuts, but why?

The mostly likely, and most reliable, trigger for rate cuts is economic recession, but nobody wants that, so why are they so keen to see those rate cuts arrive? I have no idea.

Historically, share markets have done better when interest rates are rising because that is when the economy is rebounding or humming along, generating rising profits, dividends, and share prices.

As an investor, I would much rather see interest rates rising in a growing economy, than see interest rates being cut, which is usually to stimulate a slowing or contracting economy. Personally I do not wish for the types of conditions that would require the RBA to cut rates. But that’s just me!

When we do get some nice big rate cuts, the very same people who have been calling for rate cuts to boost share prices, will be racing for the exits screaming “Recession!”

‘Till next time – happy investing!

For my current views on asset classes and asset allocations - see: