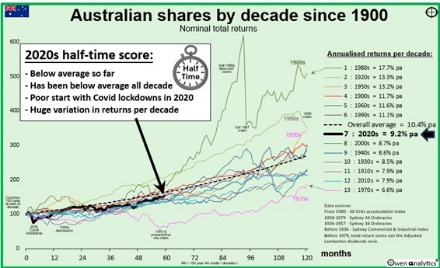

Last week I looked at the 2020s decade half-time score for Aussie shares and the picture was not very good.

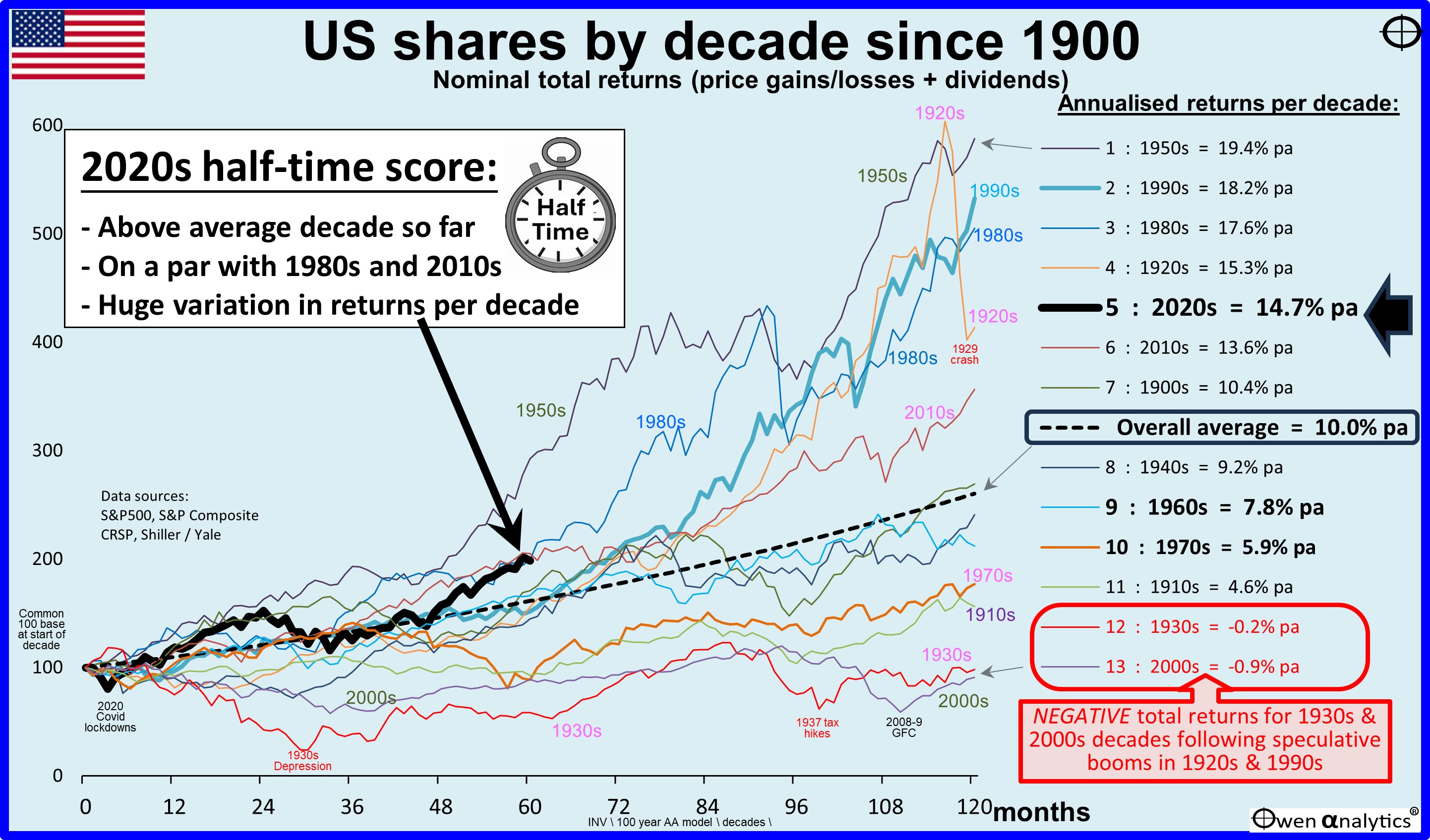

Today, we look at the decade half-time score for US shares.

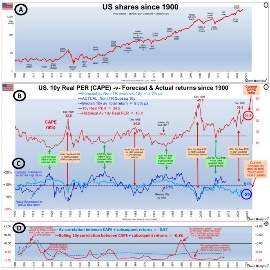

- At the half-way mark, US shares are doing well above average.

- The current speculative boom is similar to the 1920s and 1990s booms, but they were both followed by a decade of NEGATIVE total returns in the 1930s and 2000s when those booms collapsed.

- But markets don’t crash because or when they are expensive. The current boom may run on for years.

(a note on terminology - when does a 'decade' start?)

First a note about terminology, given the feedback I have received. For me a 'decade' starts on the first day the name of the decade is in the date itself.

For example, I take the '2000s' to have started at the start of the year 2000 (ie the first day that had a 2000 in the date - ie 1 Jan 2000). On that basis, I regard Covid (Feb-Mar 2020) as occurring in the '2020s' decade, because the date was Feb 2020, not the '2010s'. For me the '2010s' ended at the end of 2019, just like the '1990s' decade ended with 31 Dec 1999.

So on that basis we have had 5 full years of the 2020s so far - ie 2020, 2021, 2022, 2023, and 2024. And for me, 5 years is half a decade. And there are 5 years left in the '2000s' - ie 2025, 2026, 2027, 2028, 2029. (The following year, '2030', is the first year of the '2030s' because 1 Jan 2030 has '2030' in the date), etc.

So, because at the end of 2024 we have had 5 full years of the 2020s since 1 Jan 2020, we have are half-way through the 2020s. That's how I figure it, but each to his/her own!

2020s decade – above average

While Australia has been having a below-average decade so far, the US market (heavy black line) is posting great returns averaging 14.7% per year so far (or 100% in total). This is well above the overall average decade return for the US market of 10% pa (black dashes).

Best decades for US shares

The best decade for US shares since 1900 was the 1950s – with a total return of 488% for the decade, or an extraordinary 19.4% per year. That was the era of the tremendous post-war Eisenhower nation-building infrastructure spending boom and the Sputnik space race, but it also included the Korean War inflation, the Suez Crisis, and economic recessions 1953-4 and 1957-8.

The 1980s was also a strong decade for US shares, driven by Reagan’s deregulation reforms and tax cuts, after recovering from the early 1980s Volcker inflation-busting recessions. You can see the October 1987 crash as a dip in the line for the 1980s on the chart (at the month 95 mark), but the market quickly recovered to go on to higher levels again by the end of the decade.

The 1920s was also a strong decade. On the chart we can see that the 1920s decade was actually ahead of all decades until the 1929 crash right at the end of the decade brought it back down below the 1950s, 1990s, and 1980s lines, to finish in 4th place in terms of decade returns.

The second best decade for US shares was the 1990s, with total returns of 433% or a very high 18.2% per year on average. The 1990s started off on the wrong foot with the 1990-1 recession, but the second half of the 1990s decade was the extraordinary ‘dot-com’ tech boom, which took the market to record levels of overpricing, even more over-priced than the 1920s boom prior to the 1929 crash.

Booms never last forever of course. The two biggest booms – in the 1920s and 1990s – were both followed by very poor decades the 1930s and the 2000s. Which brings us to -

Worst decades for US shares

The worst decade for US shares since 1900 was the 2000s decade, which was effectively the unwinding of the extraordinary 1990s dot-com boom when the market reached levels of over-pricing never seen before, including the 1920s.

The US share market (S&P500 total return index including dividends) ended up in with negative returns for the whole 2000s decade.

Also posting negative total returns for a whole decade was the 1930s - the second worst decade for US shares, thanks to the 1929-33 crash that ended the 1920s speculative boom.

Wild speculative booms are followed by busts and very poor decades

The lesson for today is that massive speculative booms – like the 1920s and 1990s - always collapse eventually, and the decade after the crashes are very poor (negative total returns for a whole decade in the 1930s following the 1920s speculative boom, and negative total returns also in the 2000s decade following the 1990s speculative boom).

The best decade for US shares – the 1950s – was followed by 7.8% pa returns in the 1960s decade. This was below average but not negative like the 1930s or 2000s decades. This was because the 1950s was not an over-priced speculative boom like the 1920s and 1990s which did end in negative returns in the following decade.

Where are we now?

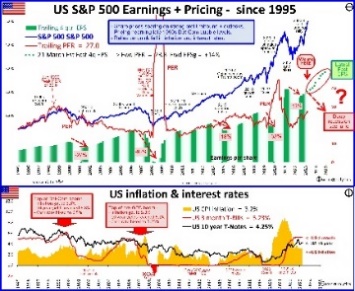

We are now in the middle of another tech boom, where the whole market is very expensive. But the broad market is still only around half as expensive relative to profits and dividends as it was at the end of the 1990s ‘dot-com’ boom.

The current boom will end in tears, of course, but what we don’t know is when. Markets don’t crash because or when they are expensive. They crash because of some trigger or set of triggers. An over-priced boom can run on for many years into even more over-priced territory until the eventual crash.

The 1990s tech boom ran for nine years without a major sell-off. The current boom is only two years old - it had sharp sell-offs in 2020 (Covid) and 2022 (Fed rate hikes). So the current boom is relatively young, and only half as expensive as the 1990s dot-com boom was before it eventually collapsed.

2025 may be the year of the big correction, but it may run on for years before the final reckoning!

As legendary investor Peter Lynch said –

“Far more money has been lost by investors preparing for corrections or trying to anticipate corrections than has been lost in corrections themselves”

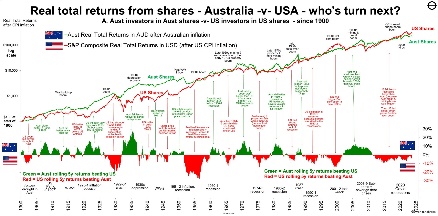

Australia -v- USA

We saw in the same exercise for Australia that the Australian market has never posted any negative total return decades – the worst decade for Australia was the 1970s with total returns averaging 6.6% pa.

The US share market has had better ‘best decades’ than Australia, but it has also had worse ‘worst decades’ than Australia, although the overall total returns over the full thirteen decades have been very similar in the two markets – around 10% pa each overall.

US share market more volatile

The US market has had higher highs and lower lows than Australia because it has been much more volatile. The annualised ‘standard deviation’ of the US share market since 1900 has been 17.5%, compared to just 13.5% for Australia (or 13.7% excluding the war-time share price controls in Australia from March 1942 to December 1946).

Comparing the charts for the Australian and US markets, you will notice that the decades of great returns and poor returns are the same for both Australian shares and US shares. Both work in very similar cycles – they both boom together and bust together, although the extent of the booms and busts in each country differ.

Essentially, Australia and the US take turns in having bigger booms and then bigger busts -

Huge variation in returns in different decades

As with the chart for the Australian share market, today’s chart for the US market also highlights the huge variations in returns in different decades. Finance textbooks say that 10 years is ‘long-term’, and share funds always warn potential investors that the minimum holding period for shares is 7-10 years.

The implication is that if you should be prepared to hold for a minimum of 7-10 years because the share market is volatile - ie result in very different outcomes over shorter holding periods. The problem is that the outcomes are very different even over 10 year holding periods, like the different decades on the chart.

Timing is everything! ‘Time-in-the-market’ only works if you pick the right decade/s

The chart shows that even 10 years is a not nearly long enough to reduce the variability of returns and provide investors with any degree of confidence that a 10 year holding period will result in returns mor or less around the long term average. Unfortunately, in the real world, the share market can generate returns well below average (or well above average) even for 20 year holding periods or more sometimes.

If you are relying on ‘time in the market’, then much of it comes down to pure luck – when you happen to have been born – which more or less determines when you start working and investing, and when you retire.

For example – if you happened to retire at the start of the 1930s or at the start of the 2000s with a pot of money to fund your lifestyle, you would have immediately faced a decade or more of very poor returns (lower lifestyles and/or run out of money sooner) in both cases.

But if you happened to retire at the start of the 1950s or at the start of the 1980s, then would have faced 20 years of significantly above average returns (better lifestyles and/or larger legacy) in each case.

That’s the great lottery of birth! But that’s too much reliance on luck for my liking!

‘Till next time, safe investing!

For the equivalent analysis of the Australian share market – see:

For more on the state of the US market and where we are in the current boom cycle – see:

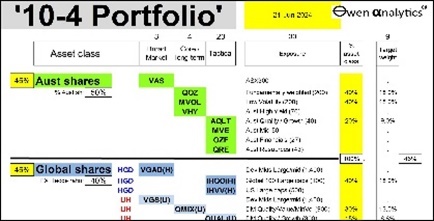

For current holdings in my long term ETF portfolio - see:

Or visit my web-site for 100+ recent fact-based articles on a wide range of relevant topics for inquisitive long-term investors.