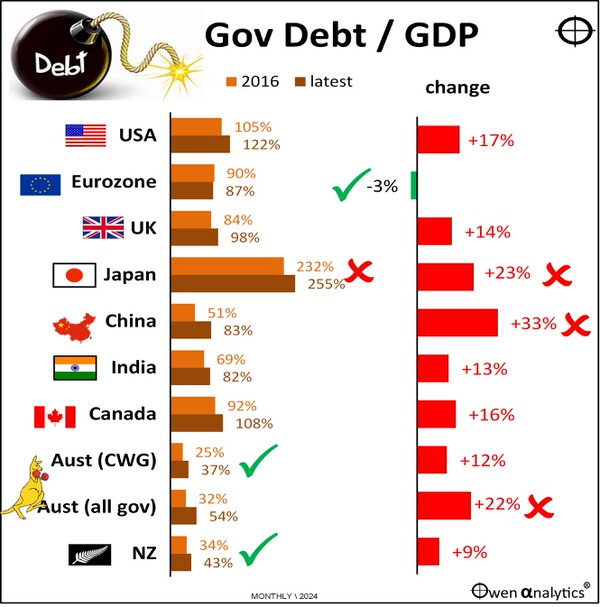

Who would want to lend to the US government? It is still running banana-republic-like deficits at -6% of GDP, debts soaring past $36 trillion or 125% of GDP (fast approaching basket cases like Argentina, Venezuela, Greece, Italy), endless ‘debt ceiling’ crises, and an incoming president promising even more un-funded tax cuts and spending sprees.

The recent once-in-a-lifetime inflation spike caused the worst losses for US bond holders in a century. Who would want to buy into that?

The answer? Almost everyone! Why?

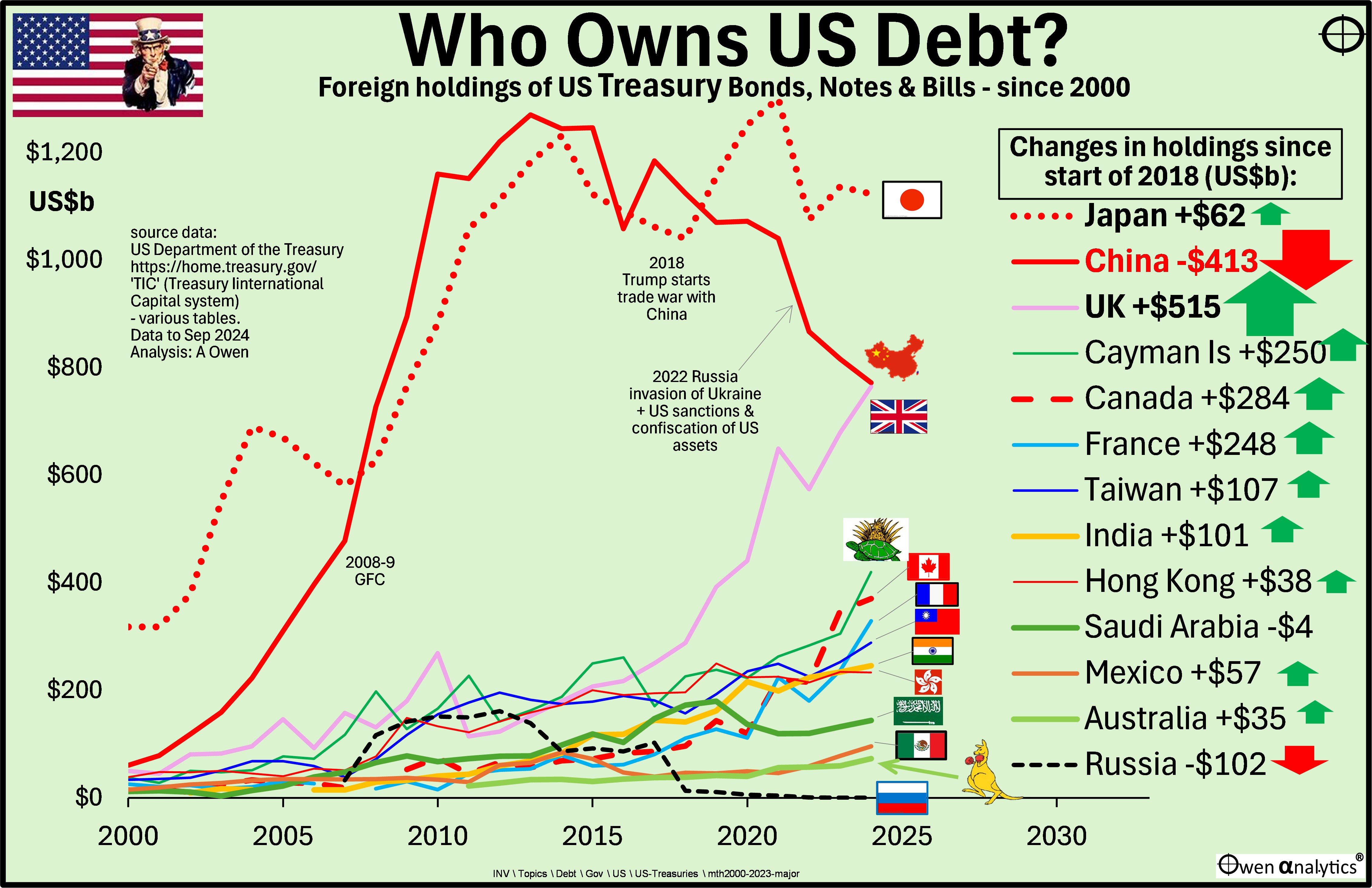

Today’s chart shows who owns US debt (ie America’s largest creditors) since 2000, who is buying it, and who is selling.

- Just about everyone is rushing in to lend more money to the profligate US government – except China, Russia, Iran (and me).

- China has dumped $413b of US debt (one third of its peak holdings) since Trump started his trade war in 2018.

- But the UK soaked up all of that and more, increasing its holdings by $515b.

The right side of the chart shows the $amount of changes in holdings of US debt since the start of 2018, when Trump started his trade wars during his first term. Since that time, foreigners in aggregate have bought an additional US$2.5 trillion in US debt. The only major countries not buying are China, Russia, and the OPEC oil exporters.

Some background info

Of the $36 trillion in US debt, one quarter of it, or $9b, is owned by foreigners. The rest is owned within the US. Check out the US debt clock here. (it’s a rather scary sight/site!)

During the period of today’s chart, the share of US debt owned by foreigners has increased from 1 in 6 dollars in 2000, to 1 in 4 dollars today.

Just under half of the debt owned by foreigners is owned in an ‘official’ capacity in foreign countries – ie country governments, including central banks, official reserves, government bodies.

The ‘non-official’ balance is owned by the private sectors in foreign countries, including banks, pension funds, insurance funds, managed funds, ETFs, and direct holdings by investors and companies.

‘Official’ (ie government) holdings have decreased from 60% of foreign holdings of US debt in 2000, down to 45% today. Therefore private sector investors (pension funds, individuals, etc) have increased their appetite for US debt over the period! Why?

‘Treasuries’

The term ‘treasures’ refers to all government debt securities, including ‘bills’ (maturities of up to one year), ‘notes’ (maturities from 1 to 10 years), and ‘bonds’ (maturities of more than 10 years). The majority of US debt securities (‘treasuries’) are ‘T-Notes’ (maturities up to 10 years).

(In the Australian market the usual custom is to use the term ‘bond’ to refer to treasuries of all maturities longer than a year. Standard 10 year government securities are called ‘bonds’ in Australia, but in America and elsewhere they are 10 year Notes or T-Notes).

China

Apart from Russia (covered below), the only big seller has been China. China had overtaken Japan as America’s largest creditor late in the 2003-8 Chinese export boom, and China remained the largest creditor until Trump started his trade wars in 2018. China has reduced its holdings of US debt by $500b since the 2013 peak. $413b of that reduction was after Trump’s trade war started in 2018.

China accelerated its reduction of US debt holdings in 2022 after the US sanctions on Russia and confiscation of Russian US dollar assets. China and other potential enemies of the US are probably selling down to avoid the risk of US confiscations in the event of an escalation in hostilities.

In addition to confiscation there is also the risk of default or repudiation of debt. Throughout history there are numerous instances where countries repudiated their foreign debts on the outbreak of war.

In Trump’s election campaign prior to his 2016 win, he raised the possibility of the US defaulting or repudiating foreign debts. He had four years in office to do it, but he didn’t of course. He raised the idea again in his 2024 election campaign, so who knows what he may do in his second term. Once again, he probably won’t default on foreign debt this time, but the mere possibility is enough to worry belligerent creditors.

Reducing holdings of US dollar assets is also part of China’s long-term plan to reduce reliance on the dollar for trade, and replace it with the yuan or some commodities-based currency (eg the BRICS initiative, and starting to pay for oil imports from Iran and Russia with yuan).

Russia

Russia had been a major holder of US debt, but it started to reduce its holdings in 2014 when it invaded and took Crimea from Ukraine (with little objection from the rest of the world, and with Merkel’s blessing in return for Russian oil and gas for Germany).

Probably inspired by the lack of resistance in taking Crimea in 2014, Putin got rid of Russia's holdings of US debt entirely in 2018, as he prepared to invade and take the rest of Ukraine. Perhaps he anticipated the US sanctions and confiscations of US dollar assets after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

This risk of US confiscation is probably a contributing factor in China’s rapid reduction in its holdings of US debt. (Iran already holds no US debt).

Japan

Japan has been the largest holder of US debt (ie largest creditor to the US) since the 1980s when US government spending, trade deficits, and current account deficits soared during the Reagan years. Despite Reagan’s grand rhetoric about ‘small government’ and ‘fiscal responsibility,’ the US under Reagan went from being the world’s largest creditor nation to the world’s largest debtor, and Japan became America’s main creditor and banker.

Japanese pension funds are stacked full of bonds under their mandates, so they have little choice but to hang on to US debt. In recent years, Japan has been sitting on just over $1 trillion of US debt, or around 3% of the total debt.

It has been a good bet for them because the 40% collapse in the Yen since the start of Abenomics has boosted returns in yen terms. (However, since almost all foreign bond holdings in pension funds are currency- hedged, the gains from the declining yen are lost on the cost of the currency hedge.)

A few years ago in I was on a panel in China with the Chief Investment Officer of one of the largest government employee pension funds in South Korea. Their asset allocation mandate was 80% bonds (half of which had to be government), 10% REITs, 10% cash equivalents. Their dilemma was how to deal with the risk of future inflation with a portfolio stacked full of bonds. Today they are still stuck with that same mandate! This is a very common problem with pension funds throughout Asia and Europe.)

Who is piling in?

The Brits!

While China has been reducing its holdings dramatically in recent years, the UK has been buying up all of what China has been dumping and more! Britian (government, pension funds, private investors) are now the proud owners of $765b of US debt (on par with China).

Why? Who knows!? UK purchases of US treasuries certainly accelerated after the massive losses on UK ‘gilts’ (government bonds) in the September-October 2022 UK bond market crisis following the disastrous Liz Truss budget debacle. (Liz who? Exactly.)

Also among the big buyers of US debt have been America’s closest neighbours, which are also Trump’s biggest targets for the highest tariffs (apart from China) - Canada (increase of +$284b in US debt holdings since 2018 ) and Mexico (+$57b). Why?

The Cayman Islands is also a big owner and buyer of US debt. It is now in fourth place behind Japan, China, and UK. Cayman is a tax-haven and favourite hiding place for dodgy hedge funds. There is a lot of money in hedge funds around the world and most of it is registered in the Caymans. Who knows what is in them. Just run.

Portfolio holdings

Almost all major pension funds in the world, plus ‘diversified’ funds and ETFs, are required to hold large allocations to treasuries, including US treasuries, under their mandates.

(It’s a textbook thing. All finance and portfolio management textbooks were written in the past three decades when bonds generated tremendous returns and provided a handy buffer in share sell-offs. But the past three decades were an unusual and un-repeatable one-off anomaly. The above-average returns from bonds were driven mainly by the great reduction in inflation and interest rates since the early 1980s.

That era of declining inflation and declining interest rates producing unusually good returns from bonds is over. We are now into the next phase of rising inflation and interest rates, which do not favour bonds. Pensioners in traditional bond-heavy pension funds will pay the price in the form of low returns and negative real returns for the next decade or so. Those portfolio management text books will be thrown away and re-written.

Fortunately, I am not driven by textbook dogma based on a very selective time in history that was unusually kind to bonds. I have been warning about rising inflation and poor bond returns since 2020, and I have been out of fixed rate bonds in advised portfolios and in my own portfolios since 2021, for fear of losses and poor returns on bonds as yields were bound to rise with the return of inflation. In 2022 bonds (including US treasuries) posted their worst losses in a century, which I avoided completely. I remain bearish on fixed rate bonds over the medium term.

(However, I do have gold in portfolios this year, and gold has been the best asset class, boosted by central banks shifting out of US debt and into gold instead. So it all makes sense).

For my current views on asset classes and asset allocations in my actual long-term ETF portfolio - see:

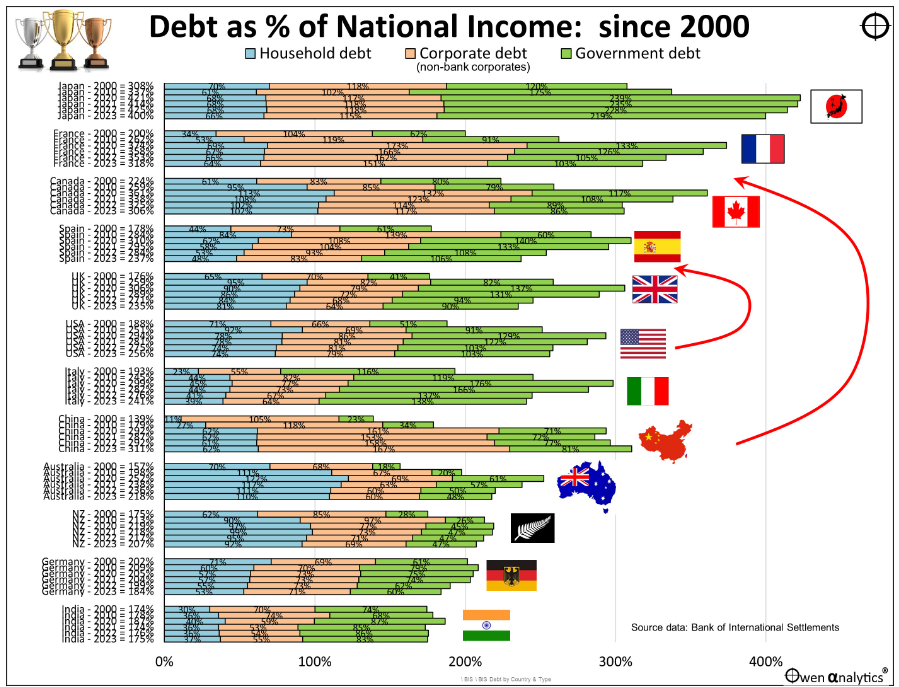

For more on government debt - see also:

‘Till next time – safe investing!