House prices seem to have soared to astronomical levels, but have they really? No!

Only if you measure them in terms of the increasingly worthless paper money that governments are deliberately debasing. The price ‘growth’ is actually just a collapse in purchasing power of the paper money governments force us to use.

‘Paper money’ is just paper (or bits of coloured plastic these days). It has no intrinsic value, and governments and their central banks deliberately set out to debase its ‘value’ in terms of how much stuff we can buy with it.

Although the sticker price of just about everything has increased due to inflation, in recent decades, house prices have actually fallen in value relative to some other real assets. Here we compare houses with gold.

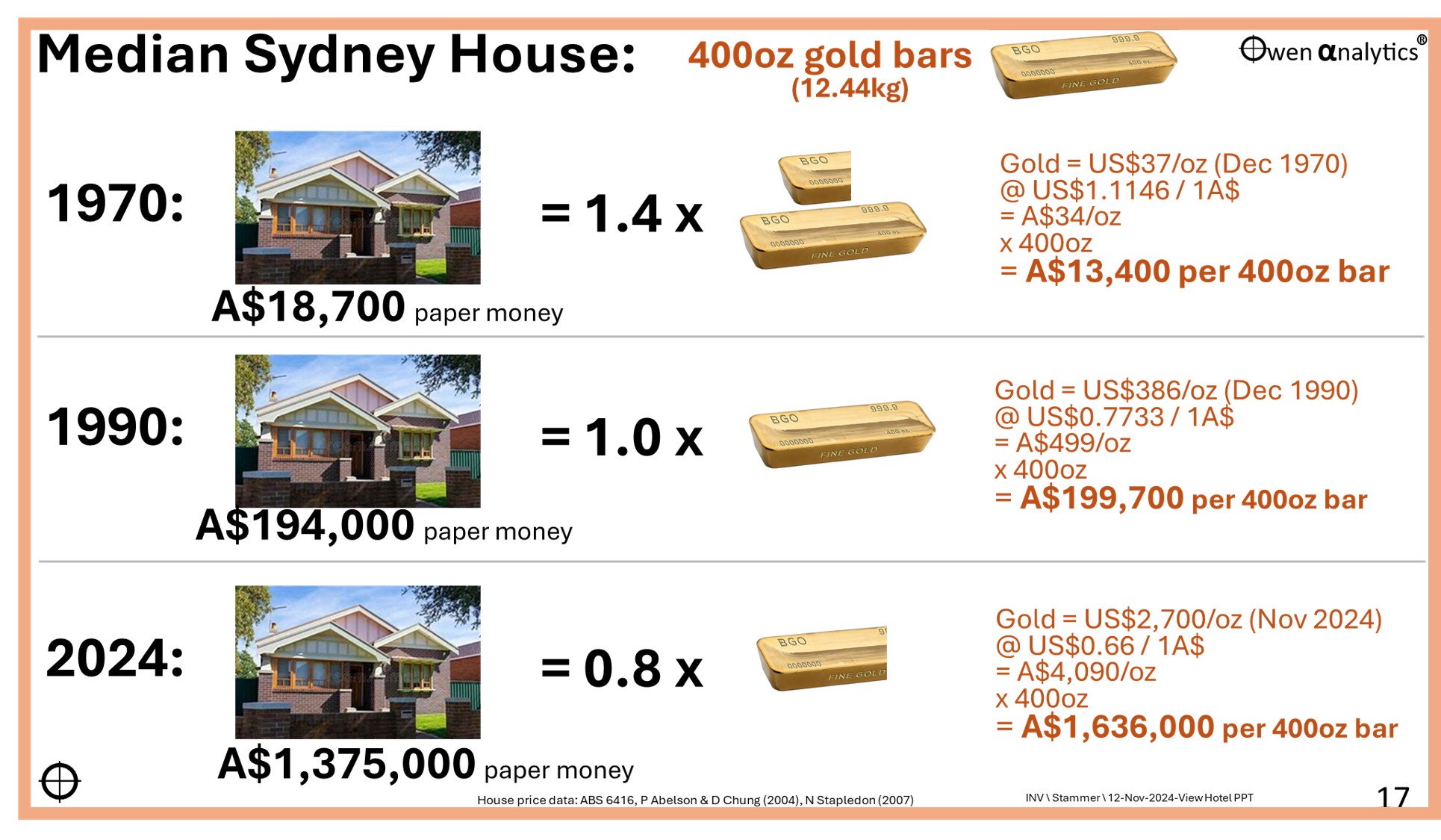

Today’s chart shows the ‘median’ house price in Sydney at three different points in time – compared to the equivalent value in gold.

Here I use Sydney ‘median’ house prices, as they are widely used in the media. (For this story I ignore the fact that the ‘median’ house today is often quite different from the median house in past in terms of size, quality, amenities, etc.)

For gold, a 400oz bar of ‘fine’ gold (‘London Good Delivery’ 99.5% purity or better) is the standard size used by banks and central banks everywhere to transfer and store gold. There are 32.15 troy ounces per kilogram, and a 400oz bar weights 12.44kg. (No, they are not easy to throw around like you see in all those bank robber scenes in the movies!)

‘Values’ in 1970

In 1970, the ‘median’ house price in Sydney was equivalent in value to 1.4 standard 400oz bars of fine gold (both A$18,700 in Australian paper money).

1990

Fast-forward to 1990 and the amount of paper money needed to buy a ‘median’ house in Sydney had increased more than 10-fold to A$194,000. But, during that 20 year period, the amount of paper money needed to buy a standard 400oz bar of fine gold had increased 15-fold to A$199,700. This was even more than the paper money increase in house prices.

The intrinsic value of ‘gold’ did not rise at all. Gold is gold. What happened was the government and its central bank reduced the purchasing power of its paper money relative to gold by 93% in that 20 year period.

As a result, the ‘value’ of a median house in terms of gold actually reduced from 1.4 standard 400oz bars in 1970 to one 400oz bar in 1990.

2024

Then, during the 34 years from 1990 to 2024, the amount of paper money needed to buy a ‘median’ house in Sydney increased a further 7-fold, from A$194,000 to A$1.375 million today.

A typical suburban family house is still a typical suburban family house. It provides the same essential shelter to a family today that it did in 1990 and in 1970. It may be a different family at each point in time, but its value as a shelter and freedom from landlords is the same. All that changed was the amount of paper money needed to buy it.

During that same period, the amount of paper money needed to buy a standard 400oz bar of fine gold increased 8-fold from A$199,700 in 1990 to $1.64m today.

Again, the intrinsic value of gold did not rise at all. A bar of gold is still a bar of gold. The only thing that changed was the government and its central bank reduced the purchasing power of its near-worthless paper money by a further 88%.

Therefore, over the past 34 years, the amount of gold required to buy a median house in Sydney actually reduced further from 1.0 standard 400oz bars in 1990 to just 0.8 of a 400oz bar today.

Not a case for gold!

I am not suggesting that people should buy gold as a pathway to buying a house in future. Nor is it intended to be a case for buying gold as an investment (I do have gold in my portfolio this year, but that is for tactical purposes only).

I am merely pointing out the problem of using paper money as a measuring stick for ‘value’. If we measure things in terms of our increasingly worthless paper money, we end up with crazy kinds of numbers that make little sense.

Rather than focusing on rising sticker prices, we need to tackle the government’s continued trashing of the purchasing power of its paper money.

What is value?

Instead of looking at paper money sticker prices, let’s look at the real-life, practical, or useful (intrinsic value) of things to people.

- The value of a bucket of water is that a family can use it to drink, cook, and clean for a day or so.

- The value of a bushel of wheat is that it can feed a family for a month.

- The value of a tank of petrol is that it can power a car to get us to where we need to go for a week.

- The value of gold is in its long-standing decorative and industrial uses, and the fact that it has been seen as a reliable store of wealth by humans around the world for more than two thousand years through countless wars, crises, and disasters.

- The value of a typical suburban house is that it can provide shelter and financial security (freedom from capricious landlords) for a lifetime, etc.

These intrinsic, practical values of commodities and everyday things remain fairly constant over time. What has changed is their sticker prices in terms of paper money. When their paper money prices rise, it is about the diminishing purchasing power of paper money we are forced to use, and that is where we should be focusing our attention.

I am not saying housing is not expensive – it is, but paper money inflation (ie declining purchasing power of money) raises the sticker prices of just about everything. But in terms of value relative to other real assets house prices have actually not risen at all. There are many other examples, but against gold, house prices have actually fallen.

‘Cost of living crisis’

Likewise, in the current ‘cost of living crisis’, the problem is NOT the rising paper money prices of everything. Rising prices are the outcome, not the cause. (Yes, anti-competitive, predatory pricing by supermarkets, airlines, and other oligopolies are a problem, but they are not the underlying, fundamental problem).

The core of the problem is government policies trashing the purchasing power of government money – including loose fiscal policies (government spending, deficits and debts), monetary policies (money printing, interest rates, and bank lending), and other government policies (including protection, subsidies, wages, uneconomic pet projects, and a host of others).

I used gold in this story as just one example of comparing the prices of houses to other real assets, but there are many other examples. Look out for my upcoming stories where I look at other types of real assets.

‘Till next time, happy investing!

For my current views on asset classes and asset allocations - see: