Welcome to the Monthly Market Monitor for September 2023

Key developments affecting investment markets during the month included:

- Share markets and bond markets post negative returns as central banks warn of possible further rate hikes to tackle inflation, which is being kept high by rising fuel prices and wages.

- Commercial property – more cuts to prices & valuations, more funds defaulting, freezing redemptions.

- Australian Housing – prices recovering, supported by tight supply and strong immigration.

- Debt stress – the ‘mortgage cliff’ thus far avoiding a major outbreak of widespread foreclosures.

- China – widening of the property/construction/finance collapse. Some minor support measures from Beijing.

- Commodities – higher for fossil fuels, but lower for industrial and battery metals. Weak demand + strong supply.

- Aussie dollar – lower again, with lower share prices.

US Congress avoids another embarrassing US government shutdown with a hasty last-minute compromise deal.

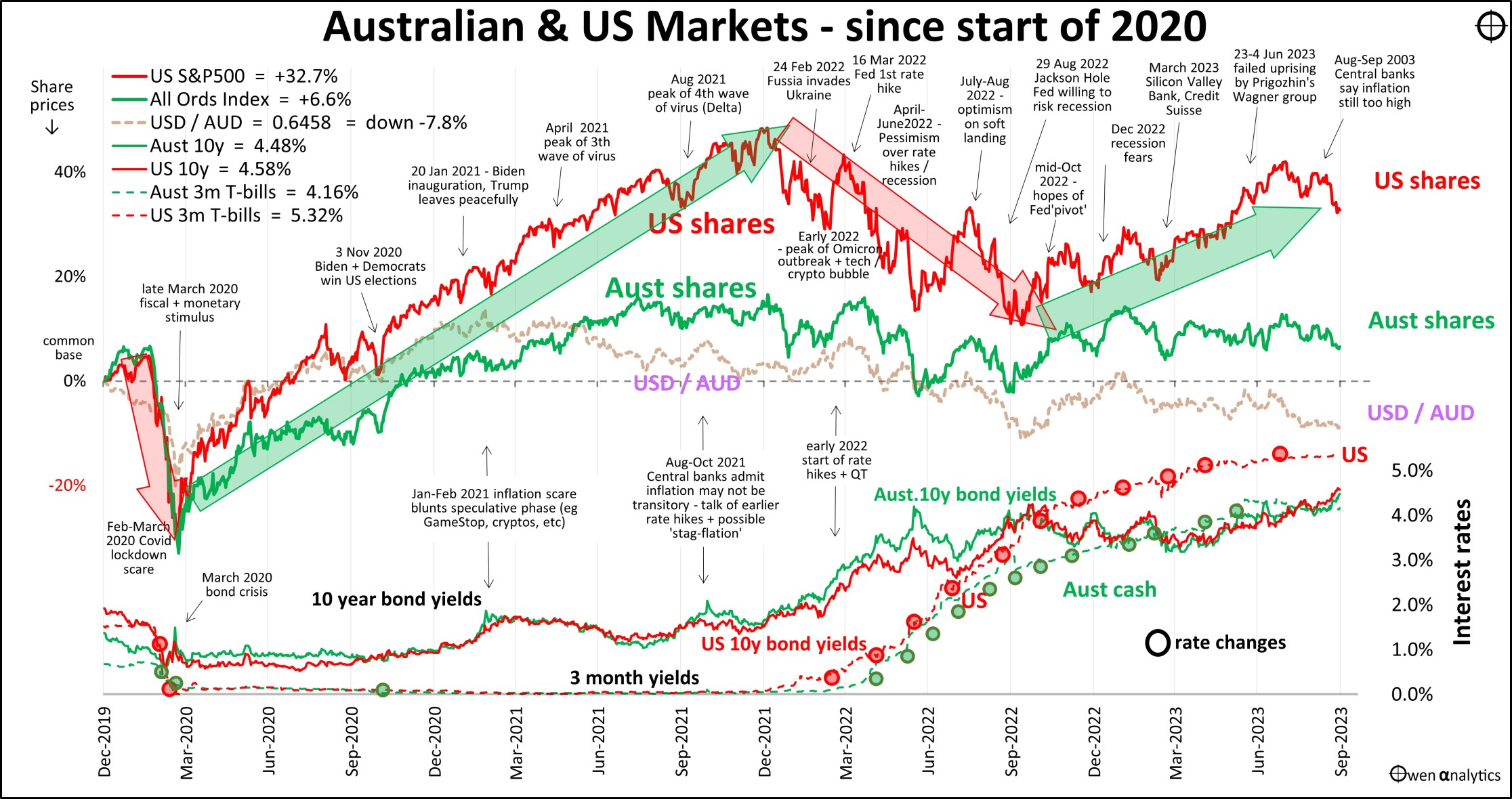

Here is our quick snapshot of Australian and US share markets, short- and long-term interest rates, and the AUD:

Global Share markets

Global share markets overall were down by another -3% in September, after falling -2% in August. But that came after two strong months, so global markets are now more or less back to where they were four months ago.

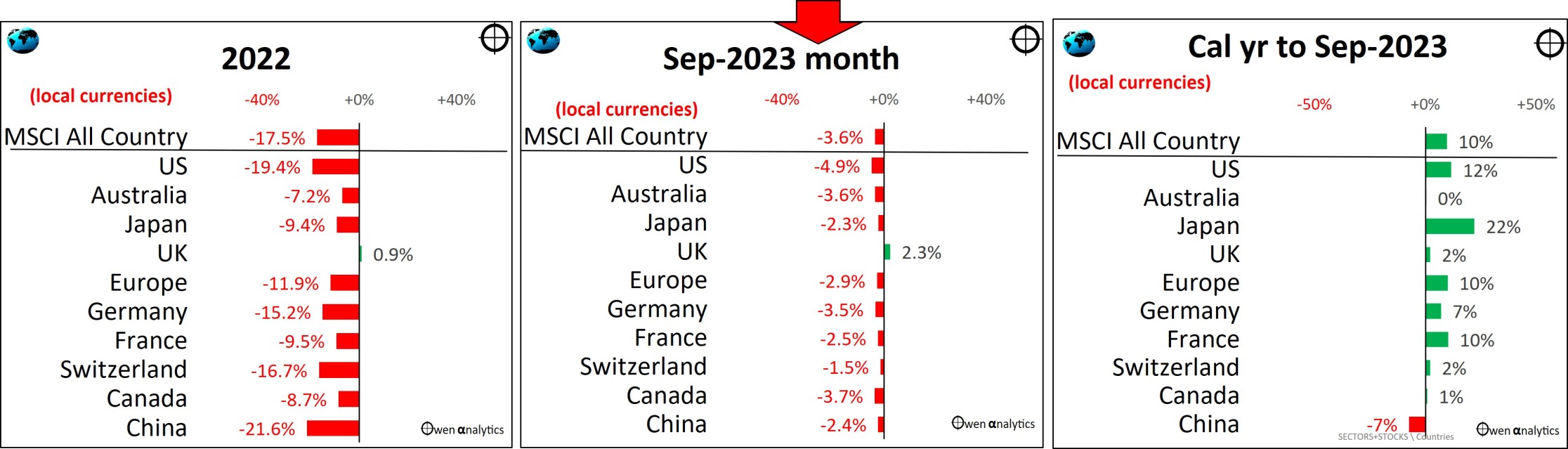

Countries

All major share markets lost ground again in September. Only the London market held up, thanks largely to rises in fossil fuel giants Shell and BP, and also HSBC Bank.

Year to date (right chart above), all the major markets are up, except China, and Australia is flat.

The modest gains so far this year have not been enough to erase the losses in 2022 (aggressive rate hikes). The UK was the only market to survive the 2022 sell-off because fossil fuels was the only sector to rise in 2022 (next charts).

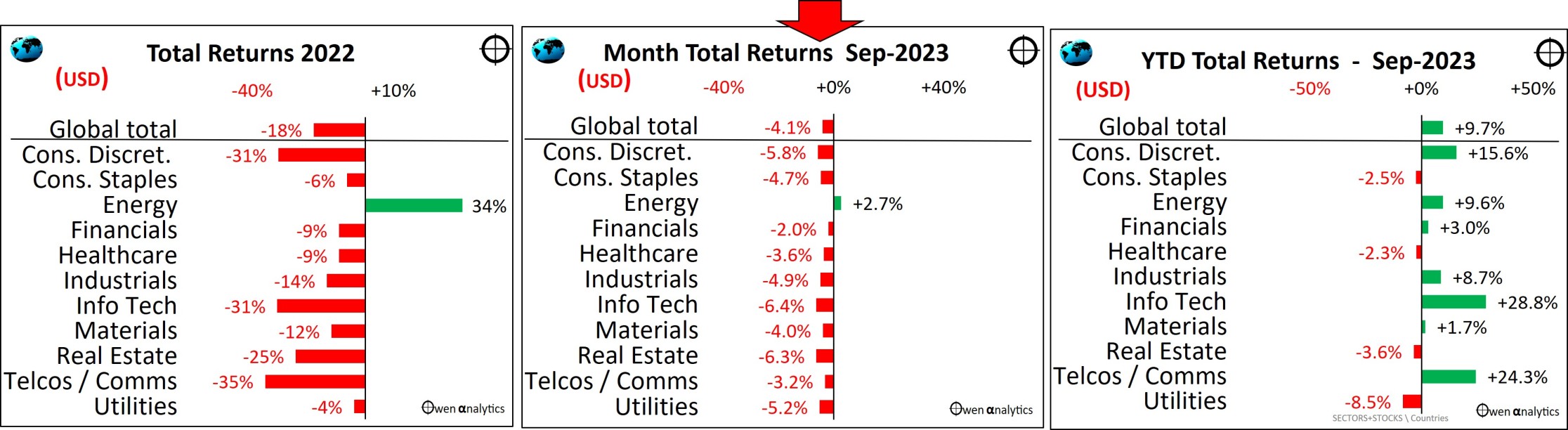

Sectors

Every industry sector was down in September except fossil fuels, with oil prices up a further +8% to above $90, gas up +6%, coal up +2%.

Rising fuel prices kept inflation rates (and interest rates) elevated, which has weighed on global markets over the past couple of months.

Year to date (right chart above), the US tech/online/A.I. giants are spread across three sectors:

- ‘Consumer Discretionary’ (Amazon, Tesla),

- ‘Tech’ (Apple, Microsoft, Nvidia, Adobe), and

- ‘Telco/Comms’ sector (Meta/Facebook, Alphabet/Google, Netflix).

The other sectors (aside from fossil fuels) are still well below the start of 2022 highs.

We will cover the issue of pricing/valuation in the next few days.

Stocks

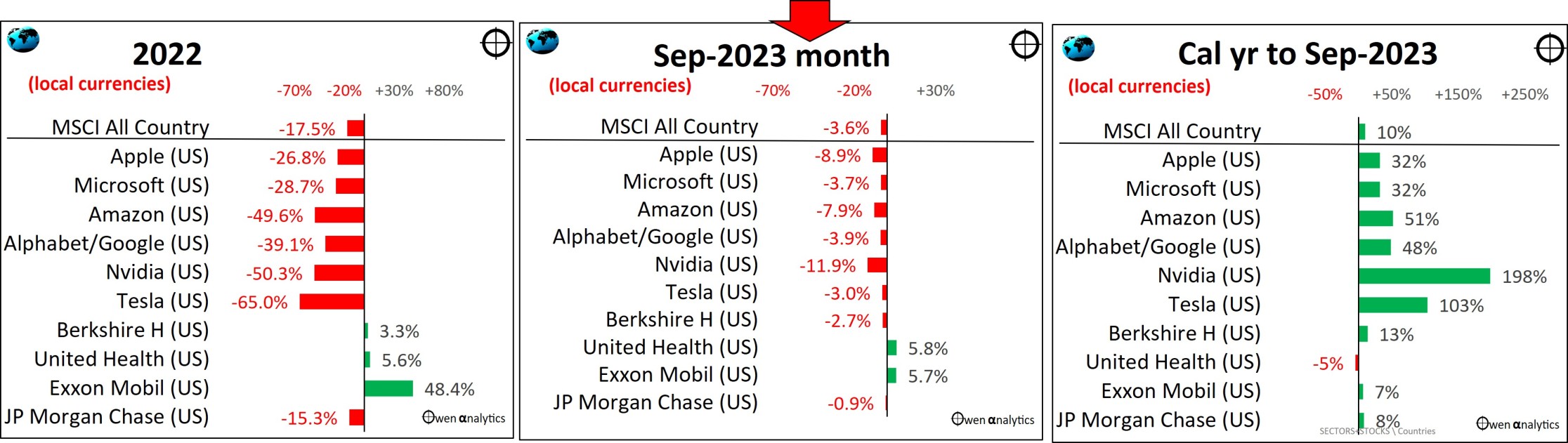

US companies dominate the list of the world’s largest listed companies (former Chinese stars Alibaba and Tencent are long gone from the top 10 list).

Most of the largest stocks were weaker in September (middle chart):

Year to date the big winners are still the US tech giants, but most are yet to recover their 2022 price declines.

The standout exception is Nvidia, the A.I. hot stock du jour. Its H100 chip (packed with 80 billion transistors on each chip) is the chip of choice for A.I. applications globally.

See also - Where are we now? – US Profits: Recession or Rebound?

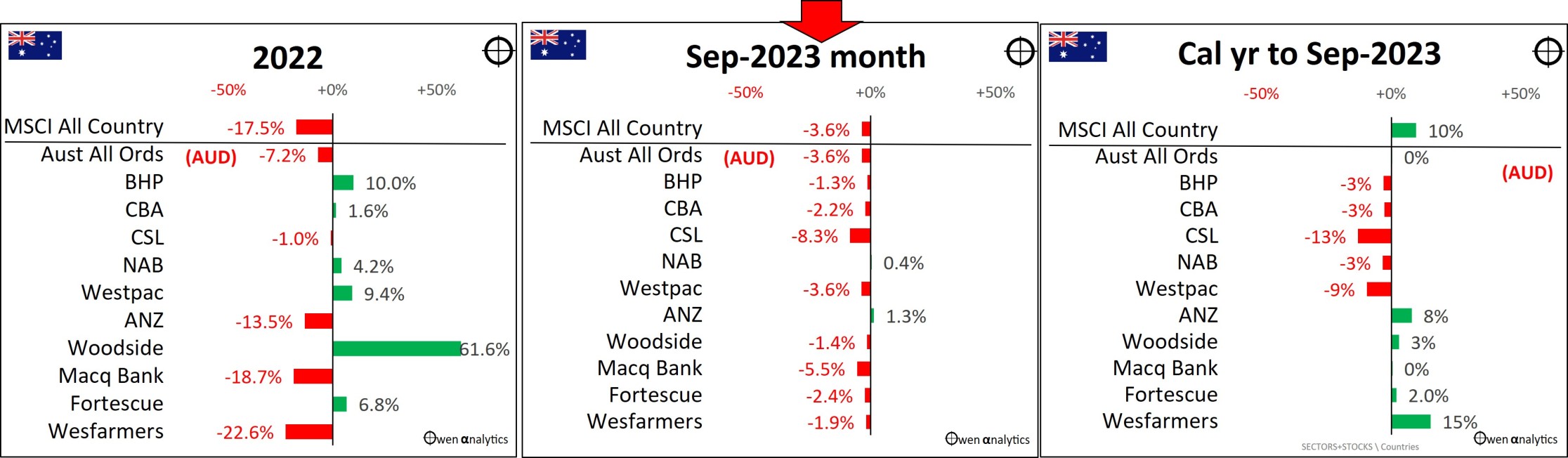

Australia

The local share market here was also weaker virtually across the board in September (except fossil fuels).

Year to date (right chart), the overall market is being dragged down by the banks and CSL, which has had some profit downgrades and also problems with its Vifor acquisition. CSL is a solid company but still very expensive.

The Australian share market held up better than most other countries in 2022 (thanks mainly to fossil fuel and iron ore producers, mainly Woodside and BHP), but Australia has been a global laggard this year.

So far this year, Wesfarmers is the main standout, with its retailers (Bunnings, Kmart, Officeworks, and now Priceline) holding up relatively well despite rising interest rates and costs.

For a rundown of the recent August ASX reporting season – see ASX reporting season in 4 charts - $40b wiped off profits! - where did it go, and why?

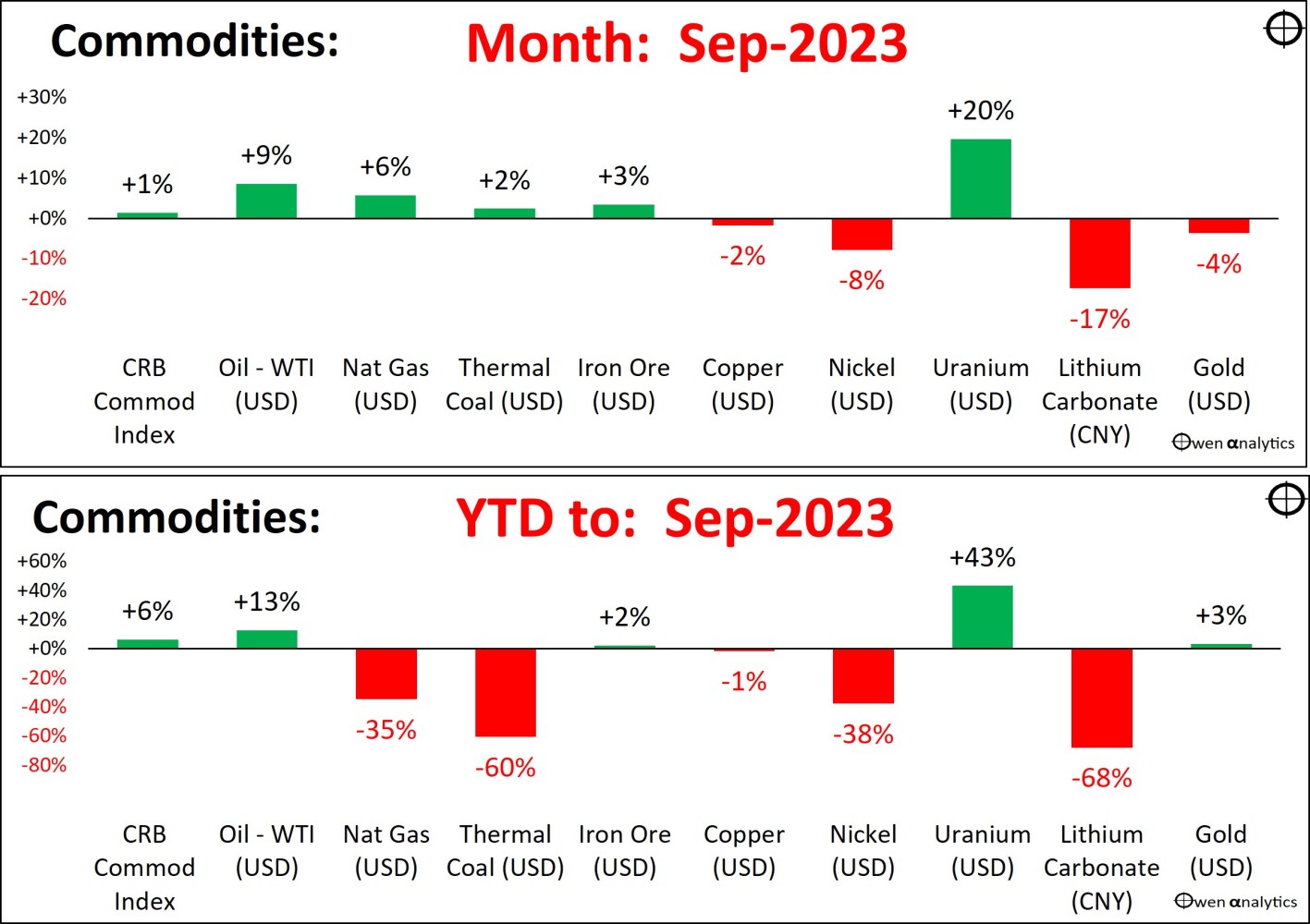

Commodities

On commodities markets, prices were higher for fossil fuels, but lower for industrial and battery metals, and gold was also down a further -4%.

Iron ore rallied on hopes of further Chinese stimulus, but thus far the stimulus announcements have been rather underwhelming.

On Chinese demand for Australian rocks – see:

The BIG picture – China’s steel production – the ‘Sydney Harbour Bridge’ index

Chinese construction – the Sydney CBD index

Year to date, most industrial commodities prices are down, with the global economic slowdown.

Battery metals have been weaker this year. On the demand side, EV sales have been weak globally, with rate hikes affecting spending. On the supply side, outlooks for higher production of lithium in particular have deflated the spectacular price lithium bubble.

The standout this year has been uranium, as a likely solution to speeding up the transition from fossil fuels.

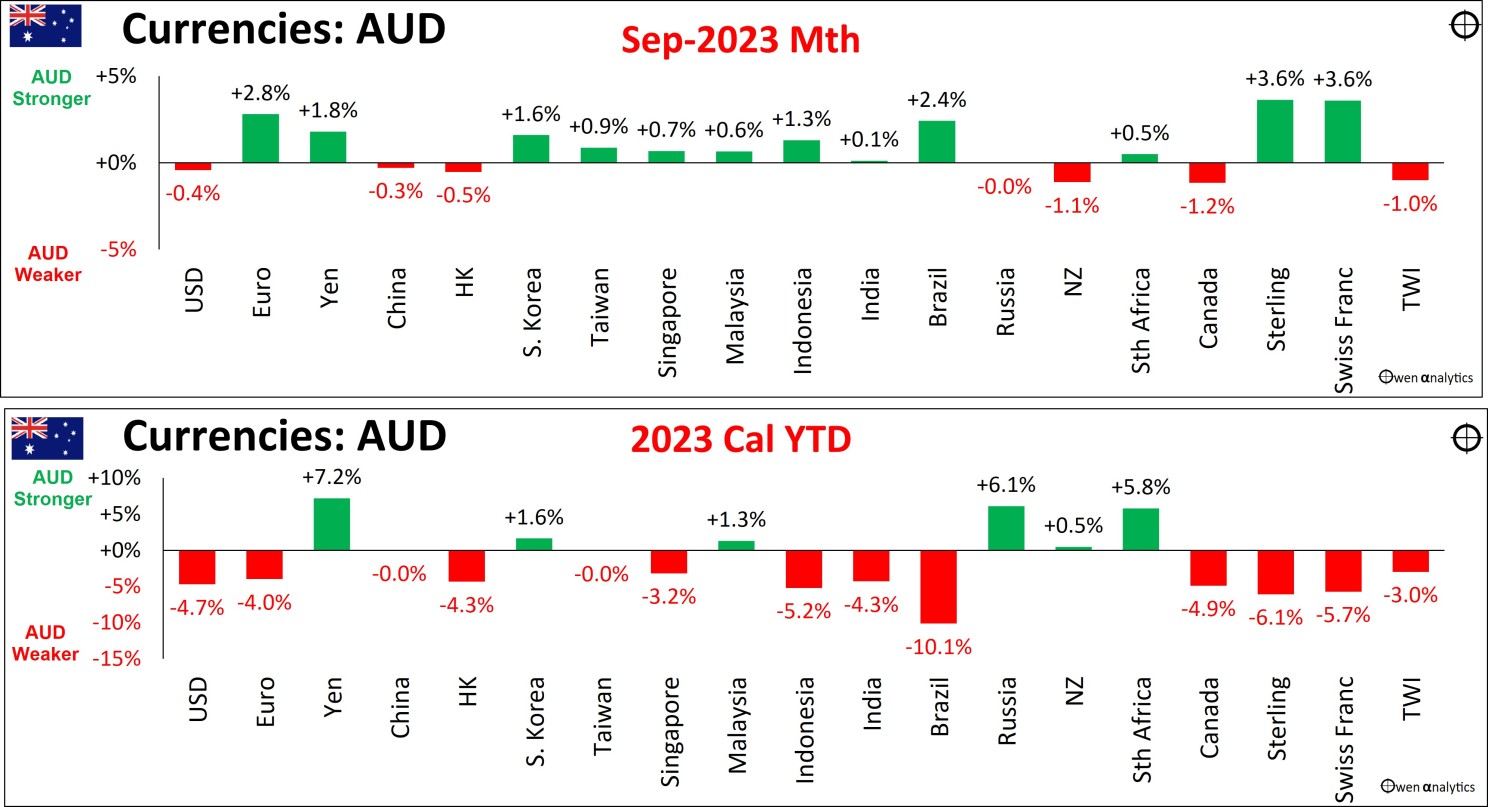

Currencies

In September the Aussie dollar fell against the USD, as per the usual pattern when share markets fall. However, the AUD was stronger against most currencies, including the Euro, Yen, and Pound

For the year to date, the AUD is down against all major currencies except the Yen, as Japan is the last country clinging on to QE and artificial suppression of interest rates and exchange rates.

Aside from the weak local share market, the main reason for the AUD slide this year has been the fact that interest rates have been 1% higher in the US than here, attracting money out of Australia and into the US.

This ‘interest rate differential’ is likely to continue for some time. Although inflation is higher here than in the US, the Fed looks more committed than the RBA to higher interest rates to control inflation. This should support the USD even if the US shares rally returns.

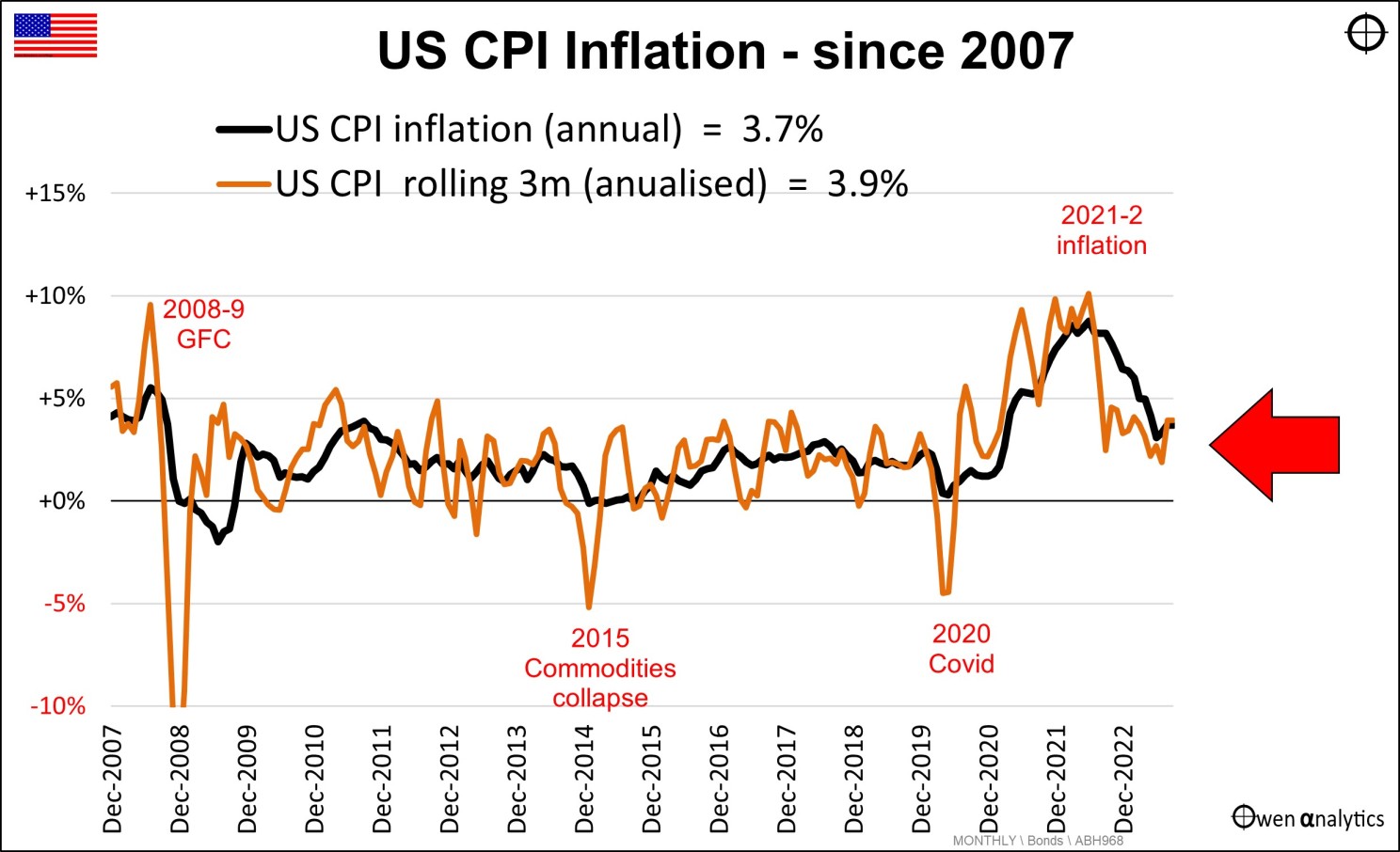

Inflation & interest rates

Inflation, and central bank responses to it, are still the biggest drivers of global sentiment affecting all markets – shares, bonds, property, currencies, spending, lending. The good news is that inflation rates continue to recede from their 2022 peak levels, but are being kept higher than target by rising fuel prices and wages.

With inflation heading back toward target ranges, central banks have more or less paused interest rate hikes, but are still warning of more cuts ahead if inflation is not contained. The exception is Japan, which has yet to get off the mark.

Wages are on the rise, but it is to pay for price rises, not higher productivity, which has stalled everywhere. Higher productivity lifts real living standards, but wage rises without productivity gains just increases prices/inflation further.

In the US – the annual inflation rate (black line) is down to 3.7%, but the annualized rolling 3-month rate (orange) was down to 1.9% but has picked up again to 3.7%:

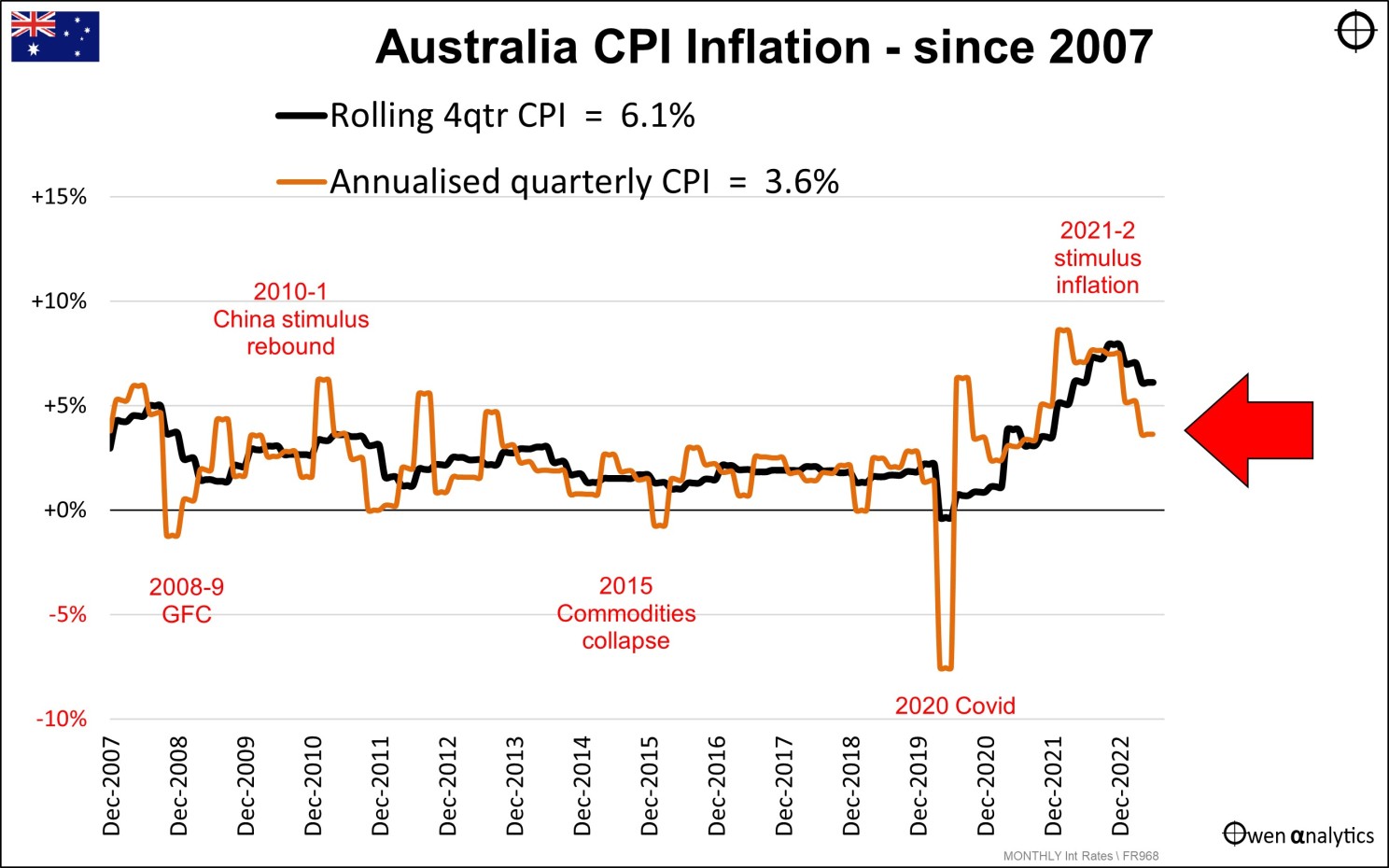

In Australia, the official annual inflation rate is still a very high 6.1%, but the annualized rolling 3-month rate is down to 3.6%

The UK is a similar story - with headline inflation at 6.7%, but the running rate was zero at one point but is now back to 3%, even though the economy has stalled, and unemployment has risen to 4.3%.

Europe is worse – with inflation still problematic at 4.3%, economies stalling, unemployment at a rather high 6.4%, and industrial producing contracting.

On the other hand, in Japan, inflation is 3.2%, the Bank of Japan is still running negative cash rates, but is finally allowing bond yields to rise.

In China, the economy has stalled, with zero inflation, falling imports, exports, and production, and a worsening property crisis. Xi Jinping has announced a handful of minor support measures, but no major stimulus measures like 2009 or 2016.

Bonds

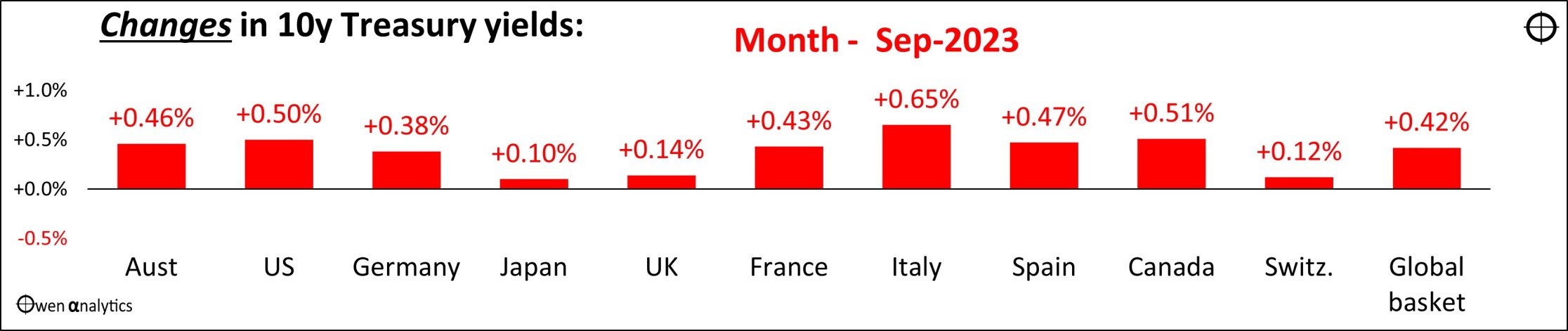

The realization that inflation and interest rates are likely to be higher for longer sent bond yields rising in all markets in September:

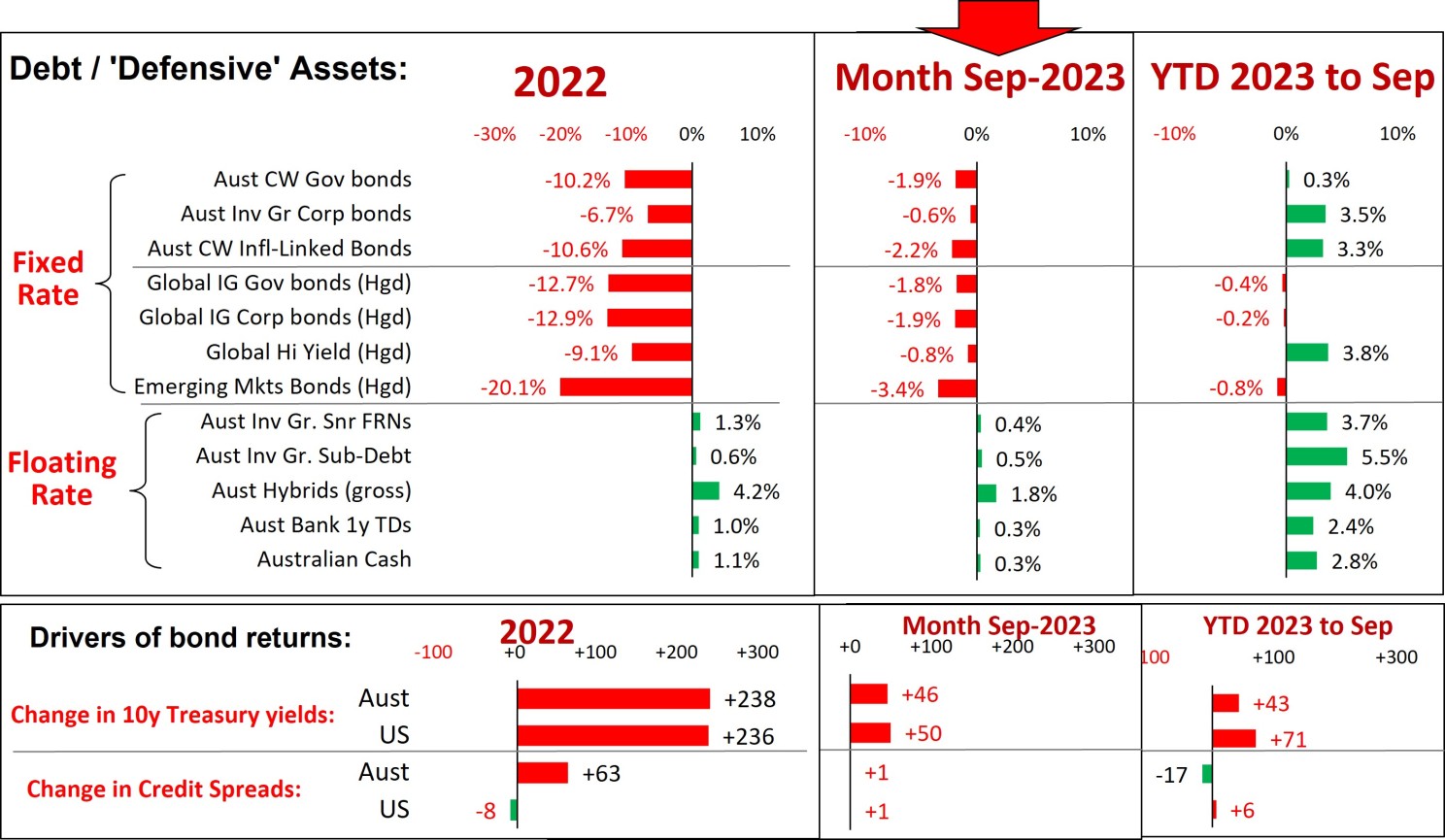

As a result, it was another bad month for fixed-rate bond returns. Here are total returns (income plus capital gains/losses) in the main bond markets.

The lower charts show the main drivers of bond returns: changes in treasury yields and changes in credit spreads.

The rising treasury yields and negative bond returns in September were not nearly as bad as in 2022, which was the worst year for government bonds in a century.

Credit spreads are a barometer of recession/bad debt fears. Spreads have not widened this year, as fears of deep recessions have receded.

Floating rate

In the lower half of the top chart are the main ‘floating rate’ markets for Australian investors. Interest rates on floating rate securities rise and fall with cash rates, so returns have been rising with the cash rate hikes since early 2022, which have hit bond returns badly.

We have heavily favored floating rate over fixed rate for the past couple of years for this reason.

Investors have been piling back into bonds because fixed rate bonds are now paying decent interest rates, compared to the ultra-low QE years. We have stayed well away from this mad rush into bonds. Why?

Rushing into fixed rate bonds for the yield only makes sense if you think bond yields are going to remain flat or fall lower. The problem is that bond yields are still likely to rise further as central banks get inflation under control.

Even if inflation does return to say 2%, cash rates will probably need to be around 4% or 5% in Australia and the US to keep inflation within target ranges, and bond yields would therefore be another 1% or so higher than cash = ie 5% or 6%.

So bond yields in Australia and the US are probably heading higher to the 5% to 6% range in the medium term, even when inflation is back to say 2%. This will mean further negative returns on bonds in the medium term.

Next stop – pricing/valuation of share markets

After the aggressive rate hikes and big sell-offs last year, 2023 has been a relatively good year for global share markets (ahead by +10% in hedged AUD, and +15% unhedged), despite some minor hiccups along the way.

Two big questions remain:

The first is a short-term issue – will have a sharp/deep recession in the US (and/or Australia). By ‘sharp/deep’ I mean including widespread personal and corporate bankruptcies and bank runs/collapses – ie like the GFC.

A sharp/deep recession is only a short-term issue for us because economic recessions are almost always over in a year or two. Share markets always rebound more quickly and strongly than expected, and usually start rebounding in the middle of recessions. Within a year or so we will be saying ‘what recession?’.

Of more importance is the second issue – pricing/valuation.

This is more serious than a ‘mere’ sharp/deep recession and bankruptcy crisis because severe over-pricing can depress returns for a decade or more, especially in real terms after inflation.

On several different measures, the US share market is severely over-priced and primed for a major correction – the only question is when. Even after the recent mini-slide in prices, returns over the next 10 years or so from current levels are likely to be significantly below average in nominal and real terms.

What can we do about this, when bonds and commercial property are also still over-priced and headed for lower returns as well?

We will tackle these questions in the next few issues of this newsletter.

Stay tuned!

‘Till next time – happy investing!