Greetings fellow investors!

Key Points

- As the US government teeters toward yet another debt crisis, it is useful to remember that US government defaulting on Treasures is not new.

- The US failed to pay maturing treasury bills three times in 1979 when Congress didn't legislate to raise the debt ceiling in time. The creditors sued for unpaid interest but were denied by the Courts.

- These were 'temporary' defaults and were rectified quickly (the principal, not the interest), but they shocked people who had believed the US government would always pay its debts.

- The default crisis was a final nail in the coffin for Jimmy Carter and Keynesianism, paving the way for the 1980s boom under Reagan with the revival of free market capitalism.

- Are we at another turning point now? Today, the US deficit and debt load are MORE THAN TREE TIMES WORSE (relative to GDP) than in 1979.

Let’s go back and put the 1979 crisis in perspective.

The 1970s - a dark decade for America

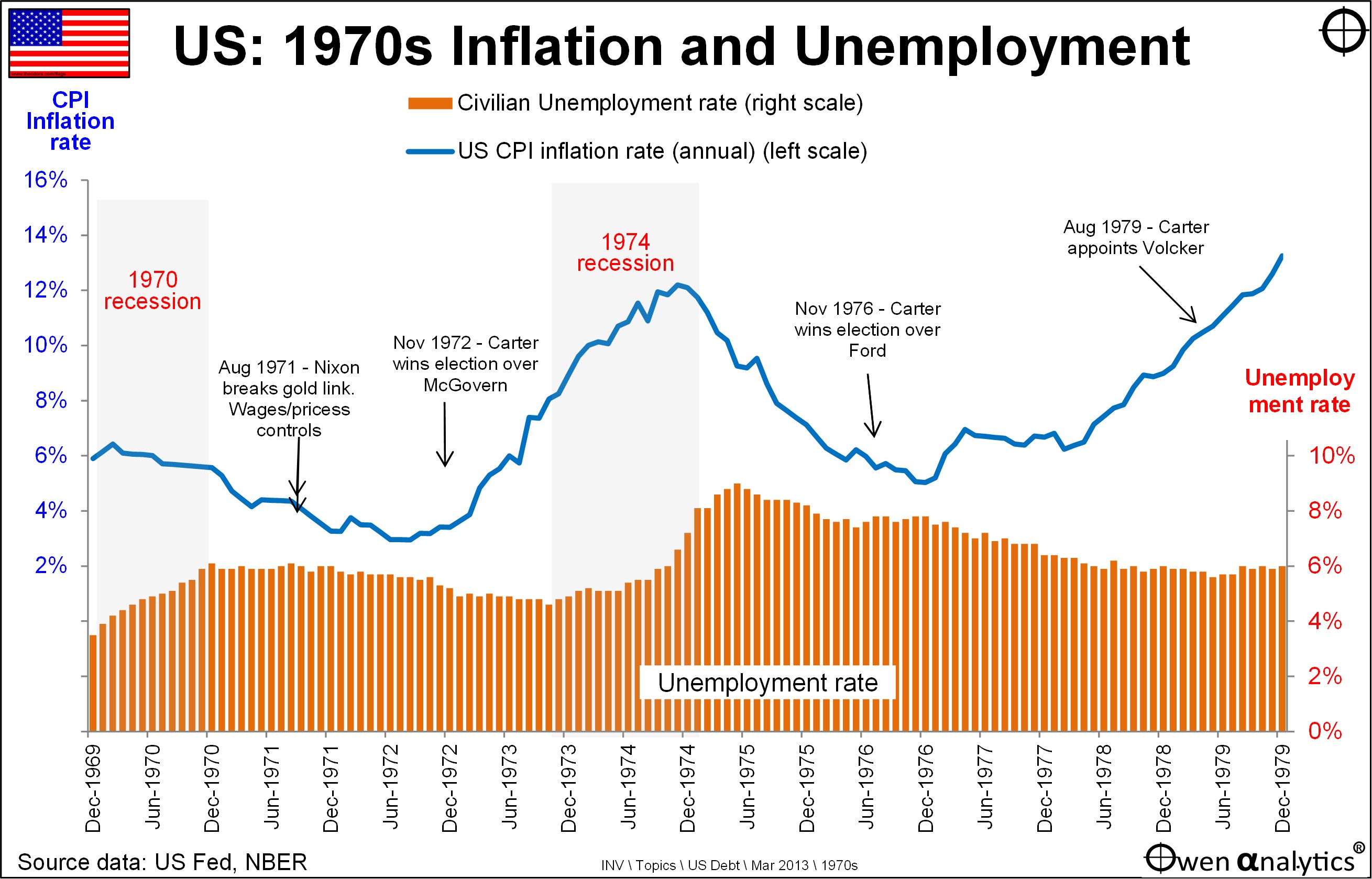

1979 capped off a long, dark decade for America. Nearly five decades of Keynesian policies were taking a heavy toll. The first chart below shows US CPI inflation and unemployment rates during the 1970s:

Inflation had started rising in the mid-1960s but it was only recognised as a problem in the early 1970s. CPI inflation peaked at more than 12% pa in November 1974, fell to 5% by end 1976, but then accelerated rapidly in 1978, and kept rising above 10% by March 1979.

Stagflation

US unemployment rose above 6% in 1971, peaked at 9% in 1975, but was still 6% in 1979, and on the rise again. This ran counter to one of the core tenets of Keynesianism, which believed high unemployment should bring down inflation. The 1970s stagflation – stagnant growth together with high inflation – plus high unemployment levels, showed that the Keynesian model was not working.

In the 1970 recession unemployment rose but inflation remained high, prompting Nixon to break the gold standard in August 1971 and institute his ‘New Economic Policy’ which included prices and wages controls (supported by Paul Volcker, then under-Secretary of the Treasury). These failed to tame inflation.

Giving up on inflation

The peak of Keynesianism in America was October 1978 when Congress passed the Humphrey-Hawkins Full Employment Law, specifically stating that fighting inflation was NOT to take priority over reducing unemployment, even though inflation was already in double digits.

It was championed by Nobel Prize winner and Keynesian, James Tobin. Tobin had been the architect of Kennedy’s 1963 tax cut plan which marked the start of the inflationary era. Tobin championed the Keynesian cause and fought against every attempt to counter inflation, even into the 1980s.

Oil crises

Another element in the 1970s inflation story was oil. Oil prices were $3 per barrel at the start of the 1970s, but trebled after the OPEC’s embargo protesting US support of Israel in the Yom Kippur war in October 1973. Oil prices nearly doubled again from late 1978 to early 1979 following the Iranian revolution crisis.

US Dollar collapse

The once mighty US dollar – the symbol of American dominance in the world – collapsed during the 1970s. By 1979 the dollar had lost half its value against the Deutsche Mark, lost two-thirds of its value against the Swiss Franc, and a third against the yen.

The problem was that the lower US dollar was not helping US manufacturers and exporters as it was supposed to in theory. The economy was stagnant, and the US manufacturers were losing out to Japan and Germany in quality and efficiency. The Japanese took the lead in making small cost-effective fuel-efficient cars while Americans were still making giant gas-guzzlers that Americans couldn’t afford to run.

Factories were closing down in America’s ‘rust belt’ and new ones were opening up in the new southern ‘sun belt’, financed by Japanese money and run by Japanese management. This came as a rude shock to many Americans troubled by what they saw as the rise of Japan and the loss of American economic dominance and sovereignty.

Interest rates

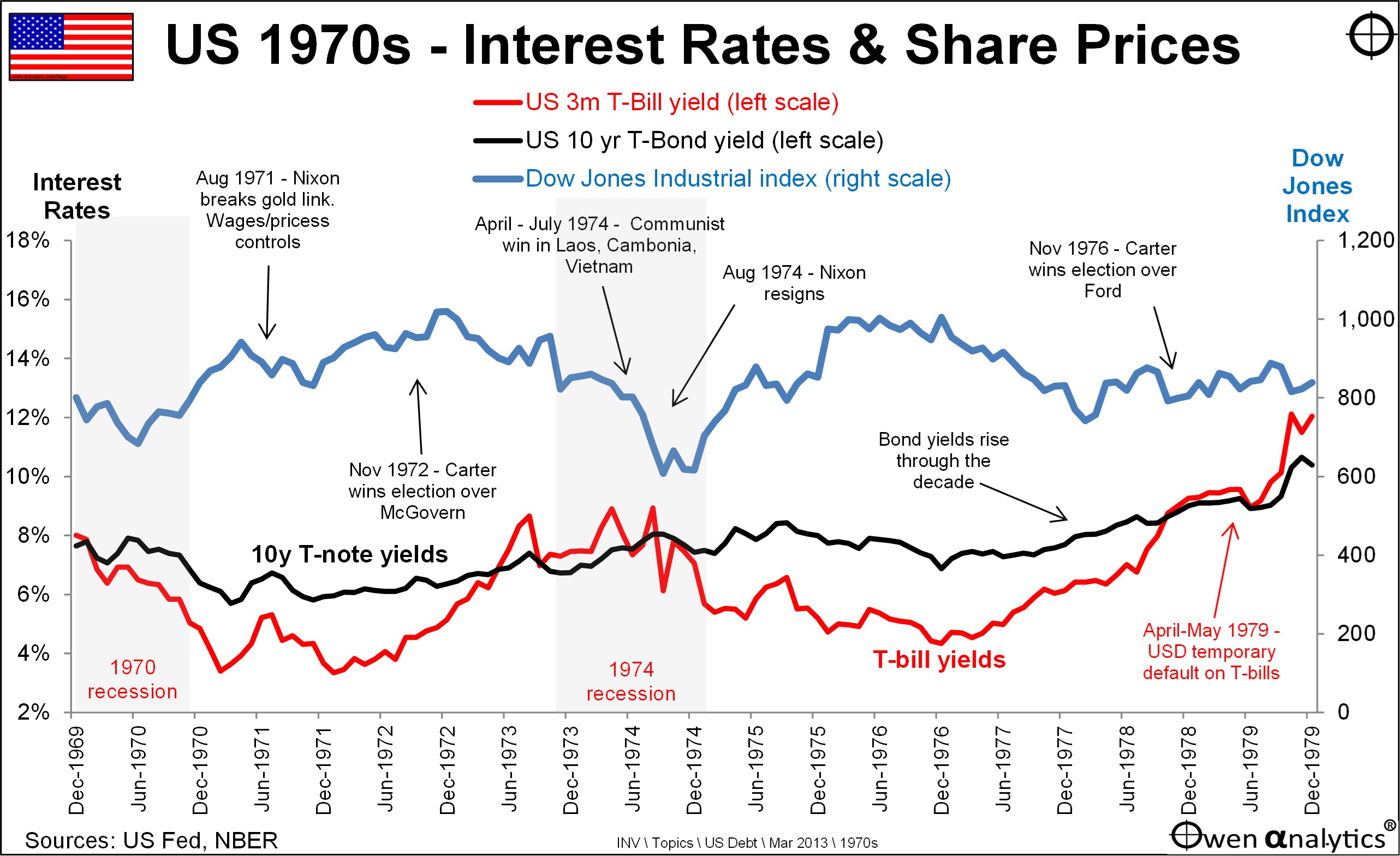

Interest rates were also at crippling levels. By 1979, yields on 10 year Treasury bonds had risen to above 9% for the first time ever in US history, and short term interest rates were back up above their 1974 peaks and heading for 10%.

Share markets - negative real returns for a decade

Shareholders suffered badly in the 1970s. Share prices were no higher in 1979, in nominal terms, than they had been 10 years earlier. But in real terms after inflation, the overall US share market fell by 50% over the decade.

Bad to worse

Domestic politics plunged to new depths with the Watergate scandal leading to Nixon’s impeachment and forced resignation in 1974. The euphoria of the triumphant NASA moon landing in 1969 disappeared quickly and the whole Apollo space program was abandoned by the mid-1970s due to lack of money and lack of public support.

In foreign affairs it was also the peak of a bad decade for America. They had lost the enormously expensive and unpopular Vietnam War to the Communists, and in February 1979 the US were also kicked out of Iran when the US-backed Shah of Iran was overthrown by the Ayatollah Khomeini’s Islamists.

Then in February 1979, China was on the march, invading Vietnam over Vietnam’s occupation of the Spratley Islands and its invasion of Cambodia. Meanwhile, with America kicked out of the Middle East, the Soviets were gearing up to march into Afghanistan.

To cap it off, on 28 March 1979, there was a nuclear leak at Three Mile Island in Pennsylvania, putting the fear of nuclear fallout into Americans on the densely populated East Coast.

Fed revolving door

Federal Reserve Chairman Arthur Burns had let inflation run out of control during his eight-year reign, so Jimmy Carter replaced him with Bill Miller in 1978, but Miller just made the situation worse. As a committed Keynesian, he opposed interest rate rises, increased money supply to further fuel inflation, and devalued the dollar in an effort to assist US exporters. Neither worked.

Funding nightmares

The US dollar collapsed in 1978 and the US government was forced to borrow from the IMF, and start issuing US Treasuries in foreign currencies for the first time. This humiliation caused a crisis in the Carter administration and Carter himself descended into despair and self-doubt.

It seemed that everything that could go wrong for America had gone wrong. This then was the environment in which the 1979 defaults occurred.

The debt ceiling - again

In April 1979, Congress failed to legislate to reach a deal in time, and the Government hit the debt ceiling. Without the ability to borrow more, it had to decide who not to pay. It could ‘close down the government’ and stop paying employees or suppliers, or it could stop paying interest and maturing principal on its debts – Treasury bills, notes and bonds. It chose the latter.

Who not to pay?

In the 1979 defaults, the US Government did not treat all creditors equally. Most Treasury bills, notes and bonds were held by banks and other financial institutions like insurance companies and pension funds, with a small minority held by individuals. In 1979, the Government chose to repay the main institutional creditors in full, out of fear of triggering a banking crisis.

Instead, Treasury chose to default on 6,000 individual T-bill investors.

- On 26 April 1979, the US Treasury failed to repay $41 million of maturing Treasury bills. They were paid 20 days late on Thursday 17 May 1979 after the Government found some money.

- Then again on 3 May 1979, Treasury defaulted on another $40 million. These were also paid 14 days late.

- Then again on 10 May 1979, Treasury defaulted on yet another $40 million of maturing T-bills. These were also paid on 17 May.

Investors barred from suing for lost interest

Treasury refused investors’ demands to reimburse the $325,000 in lost interest on the late days and so investors were forced to sue the US government in a class action (Claire G. Burton v. United States, US District Court, Central District, California, D 79, 1818LTL (Gx)).

Unfortunately the Court threw out the investors’ claim by relying on a 1937 Supreme Court ruling that, “interest does not run upon claims against the Government even though there has been a default in the payment of principal”. (Smyth v. United States, 302 U.S. 329, 1937).

It came as a rude shock for Americans to discover that not only had their Government defaulted on its debts, but there was a decades-old judicial precedent establishing that it didn’t legally owe interest when it failed to pay on time!

Credit premium on T-bills

When the money market opened on Friday 27 April 1979, the day after the first default, T-bill yields spiked up by 50 basis points and this default premium on US T-Bills remained even after the default was rectified the next month. This demonstrates that the US Government has indeed defaulted on its debt (at least temporarily), and that US T-bills are not ‘risk-free’, but are prone to a credit default premium in their pricing.

Last straw for Carter

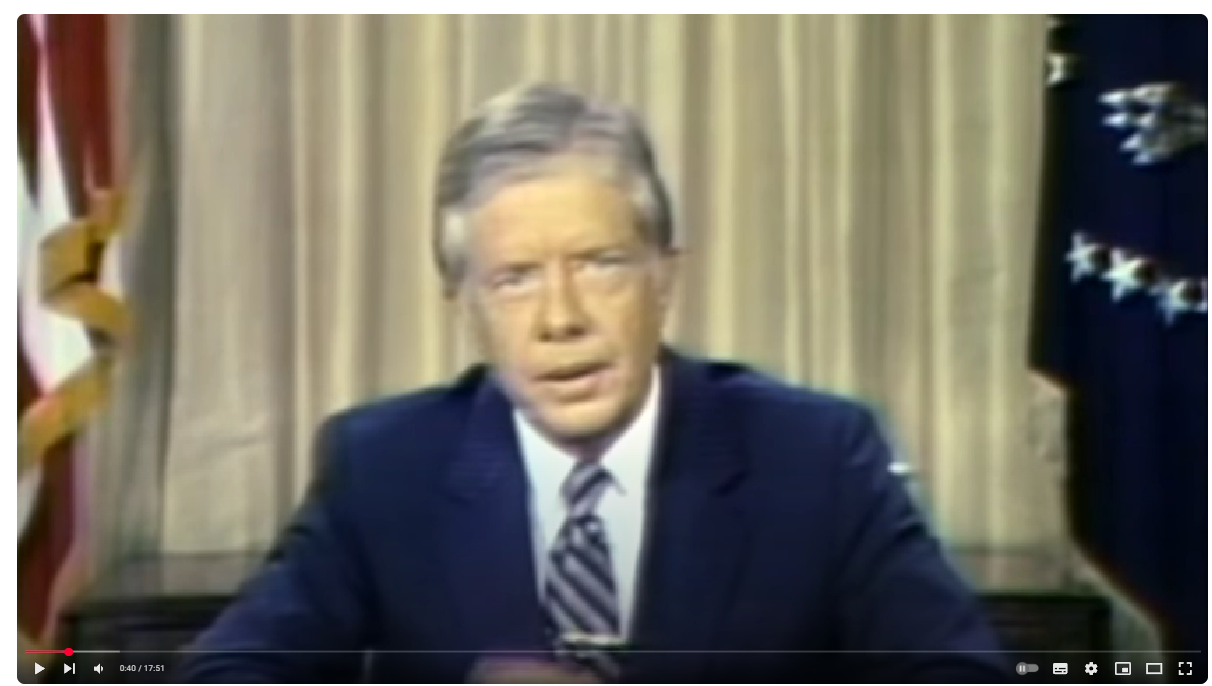

This was the end for the Carter administration. Carter threw in the towel in his televised ‘malaise’ speech on 15 July 1979, in which he succumbed to the national sense of hopelessness:

“… I realize more than ever that as president I need your help… We are confronted with a moral and a spiritual crisis…..It is a crisis of confidence. It is a crisis that strikes at the very heart and soul and spirit of our national will. We can see this crisis in the growing doubt about the meaning of our own lives and in the loss of a unity of purpose for our nation. The erosion of our confidence in the future is threatening to destroy the social and the political fabric of America”. (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KCOd-qWZB_g)

Carter’s admission of defeat and despair marked the nadir for the American post-war prosperity and the end of the grand Keynesian dream that had dominated political and economic thought since Franklin Roosevelt’s election in the depths of the 1930s depression.

Darkest before the dawn

But all was not lost. The darkest days of 1979 turned out to be just before the dawn of a new era for America.

Jimmy Carter removed Bill Miller after just 18 months as Fed Chairman (yes, the President can fire a Fed chair), and installed Paul Volker in his place. Following Volcker’s confirmation on 6 August 1979, he set about immediately to switch Fed policy from Keynesianism to Monetarism, as advocated by Friedrich Hayek, Keynes’ arch rival, and Milton Friedman. Volcker instituted a new policy that clearly elevated the low inflation goal above the low unemployment goal, and focused the policy tools on tight control of the money supply to bring down inflation.

Thatcher in UK

Meanwhile across the Atlantic, the UK had suffered a similarly debilitating and demoralising 1970s – with stagnant growth, high inflation, high unemployment, high interest rates, high tax rates and negative stock market returns and a humiliating IMF bailout. Following the ‘winter of discontent’, a series of bitter industrial disputes and strikes under Labour, British voters elected Margaret Thatcher’s Tories in the 3 May 1979 elections in the largest electoral swing seen in Britain since 1945.

Painful medicine

To Carter’s credit, he honoured his promise to let Volcker increase interest rates until he brought down inflation, even though it triggered a deep double-dip recession that began in 1980. The Fed discount rate peaked at 13% in Feb 1980 and T-bill yields peaked at 16% in March when inflation peaked at 14.6%, as the economy slid into recession and the unemployment shot up to double digits.

Volcker’s money supply targeting policy only lasted a couple of years (after which he switched to targeting the price of money - ie interest rates), but it was enough to break the inflationary cycle.

Reagan, and the return to capitalism

In conditions like these, and also the humiliating Iranian hostage debacle, it is hardly surprising that the November 1980 Presidential election was won by Ronald Reagan in a landslide victory. Volcker, Reagan and Thatcher led the macroeconomic revolution in the 1980s, towards smaller government, lower tax rates, privatisation of industries and deregulation of markets. The result was lower inflation, lower interest rates, lower unemployment rates, and a return to economic growth.

1979 was the turning point and the start of the 1980s which saw the victory of monetarism and market capitalism over state-directed Keynesian, socialism and communism. In China, Deng Xiao Ping turned his back on communism as an economic system and started down the ‘capitalist road’. Within a decade the Soviet system and communist eastern bloc had collapsed.

US default again?

Another US default on Treasuries is not out of the question. It probably would be a temporary default, like the 1979 episodes, and not a complete rescheduling like Greece.

The US has plenty of money, and it can always print as much as it likes. The problem is primarily one of politics, not insolvency.

Another default may be enough of a shock to get the parties together to work on real solutions. It may provide the catalyst for the next era of growth and prosperity, as happened in 1979.

We are probably not yet at that point. Huge policy shifts usually only come about from the depths of crippling crises – like the 1930s Great Depression (80% stock market crash, 30% unemployment, severe price deflation, deep nationwide collapses in industrial and agricultural output), or the 1970s (double-digit inflation & unemployment, social unrest, political crises, military failures).

We are probably not at that point yet. However. . .

History repeating?

I wrote the above story in 2013 after the US debt crisis and credit downgrade in 2011, and the debt ceiling crisis and government shutdowns in 2012. My 2013 story was published on Firstlinks, and also picked up and summarised in the Australian Financial Review on 13 October 2013: - Think the US won’t default? It has before: three times

As I read this again in 2025, I am struck by the number of similarities brewing with the 1970s. A lot has changed since the 1970s, but the US has probably stumbled closer toward similar levels of crisis across a range of fronts – economic, political, social, racial, fiscal, loss of public faith in government and institutions.

There are differences today of course. However, the US deficit and debt load are now MORE THAN THREE TIMES WORSE than in 1979:

- US federal government debt: was 31% of GDP in 1979, but is now more than 120% today.

- US federal government annual deficit: was less than -2% of GDP in 1979, but is more than -6% today.

We live in interesting times!

For more details on the 1979 defaults – see

‘The Day the United States Defaulted on Treasury Bills’ – TL Zivney and RD Marcus ‘The Financial Review Vol. 24 August 1989, pp. 475-489. Published by The Financial Review (US)

‘Till next time – safe investing!