Key points:

- The US dollar is hardly in decline or on its last legs – the main problem is that it’s too strong – demand exceeds supply.

- The biggest enemy of US producers and exporters is not China, the chief culprits are Japan, Europe, and UK, as they have trashed their currencies to help their exporters, far more than China has.

- Trump needs to bring down the dollar, but can he do it without crashing stock markets and sending bond yields higher?

End of the US dollar? – hardly!

With all the chaos in the US - trade wars, up-ending global alliances, ballooning US government deficits and debts, and talk of recessions – I am receiving an increasing number of questions along the lines of: “Is the US dollar in trouble?”, and “Is this the end for the US dollar as the dominant / safe haven currency?”

Fair question – but the problem is actually the reverse. The main problem is that US dollar is too strong and has been rising steadily over the past decade and a half. Trump needs a lower dollar to help US exporters.

Trump’s tariffs on imports from China in 2018 were neutralised by China quietly devaluing the RMB. But the continually rising US dollar has hurt US producers and exporters competing with all countries, not just China.

US dollar in context

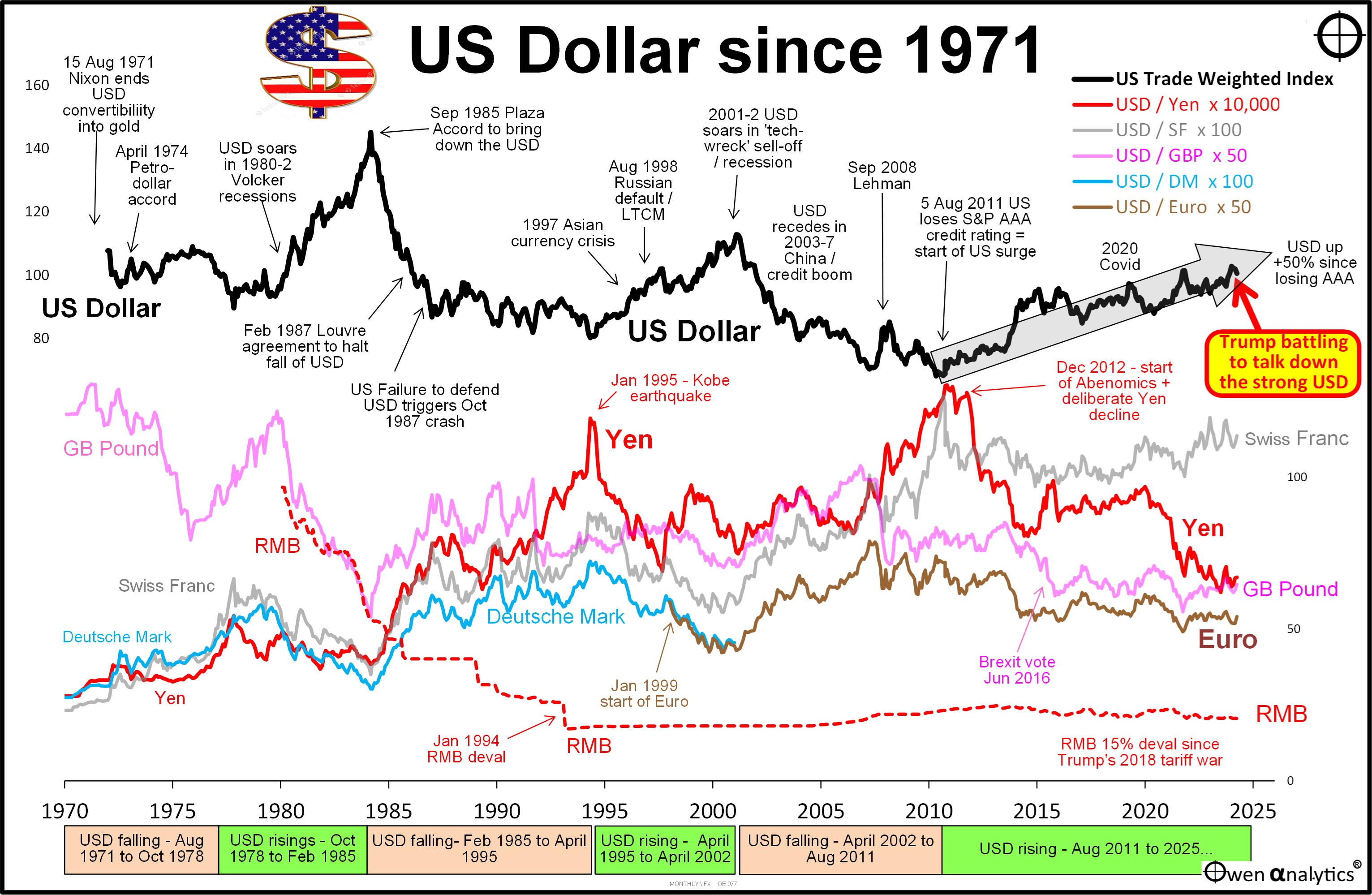

Today’s chart tells the story of the US dollar since Nixon took the dollar off the gold standard in August 1971 (actually the gold fix ended in March 1968, Nixon just made it official in August 1971). The black line in the upper section is the US dollar trade-weighting index against its major trading partners.

The lower section shows other major currencies relative to the US dollar. I have used various scales for each to get them on the one page, so we can see how they move together relative to the dollar.

We can see from top section that the US dollar is pretty much at the same level as it was in 1971, relative to the basket of its trading partner currencies.

The phases of rising USD and falling USD are noted along the bottom of the chart. The dollar has been in a rising phase since 2011.

US dollar rising strongly since 2011

In 2011, the US government suffered yet another ‘debt ceiling’ / ‘government shutdown’ crisis (ho-hum, we’ve seen dozens of those before!), and the dollar hit its post-1971 low point in early August.

When credit rating agency S&P stripped the US government of its AAA credit rating on 5 August 2011, US and global investors suddenly raced in to buy up US dollars and US debt, sending US bond yields lower, and the US dollar higher. The dollar has been on a strongly rising path ever since.

Since losing its AAA credit rating in August 2011, US dollar is up +50% against its trading partner currencies, and it is still rising. In recent years, there has been strong buying from global investors (including Aussie super funds) chasing returns from the booming US tech boom. When we buy US shares, we need to sell our own currency to buy US dollars to buy the shares – this depresses our currency and lifts the US dollar.

‘Abenomics’ and the Yen

The biggest enemy of US producers and exporters is not China. It is Japan, because the single biggest reason behind the strong rise in the dollar since 2011 has been the deliberately engineered collapse of the Yen.

Shinzo Abe returned to power in Japan in December 2012 on a platform of openly and deliberately trashing the Yen to help Japanese exporters. It worked a treat – with the Yen halving in value against the dollar, putting a rocket under Yen corporate revenues, profits and share prices.

The halving of the Yen effectively halved the prices of Japanese cars and other Japanese imports into the US. So, if Trump slapped a 100% tariff on Americans importing Japanese cars, it would just neutralise the 50% yen devaluation, that’s all.

Euro

Over the same period, the European Central Bank engineered a 30% decline in the Euro against the dollar, making European imports into US 30% cheaper. Europe achieved a lower Euro through a combination of zero/negative interest rates, QE money printing, plus a seemingly never-ending stream of destabilising political crises all across the zone, from the core to the periphery.

Pound

Across the channel, the Brits did their best to trash the Pound – with Brexit, repeated budget crises, political crises, revolving door PMs, and the spectacular September 2022 UK bond crisis. The pound has fallen by -25% against the dollar over the past 10 years.

China

Meanwhile, China managed to quietly devalue its RMB by 15% since Trump’s 2018 trade war. Trump’s first term was a wake-up call for China to extend its supply chain into lower wage countries like Vietnam and Cambodia, to shift its focus toward global domination of higher value industries like EVs, solar/wind technologies, rare earths, battery metals processing, surveillance tech, ai, and also to step up its Belt-and-Road political / financial / military alliances into Europe, Middle East, Africa, and the Pacific.

Safe haven curse

The bottom line is that the rising US dollar undermines and neutralises Trump’s tariffs on imports from countries with declining currencies. The more crises Trump creates, the more people flock to the US dollar as a safe haven, further neutralising the effects of the tariffs.

Trump’s dilemma.

Trump needs a lower dollar to help US producers and exporters compete against other countries that have been trashing their currencies relative to the dollar. He also needs lower bond yields to lower the cost of financing the deficits and refinancing existing debts. Achieving both at the same time will be extremely difficult.

He could send the dollar lower by threatening to default on US debt (he first threatened to do this in the lead up to the 2016 election – he had four years to do it in his first term, but he didn’t).

This time there is a plan to convert foreign holdings of long-term US bonds into perpetual bonds or 100-year ‘century’ bonds. If done unilaterally it would amount to a ‘default’ and send the dollar lower, but it would also send bond yields higher to reflect a default premium. That’s the last thing Trump wants. He needs lower bond yields to lower the cost of refinancing $9 trillion of US debts that will fall due this year.

There has to be another way. If he could make it converting bonds into ‘century’ bonds part of a negotiated agreement over tariffs with each country (see below), then perhaps it could avoid being a technical ‘default’ and this may keep yields contained. Interesting times indeed!

Mar-a-largo agreement to bring down the dollar?

There is talk in the US of Trump getting other countries to agree to sell dollars to bring down the dollar. It would be a relatively easy negotiation – just make it a condition of lifting US tariffs on imports from each country if they agree to buy more US products, pay for them in US dollars, and then sell dollars to buy their own (or other) currencies (plus perhaps converting each country’s holding of long-term bonds into ‘century’ bonds at lower coupon rates).

One complication would be that selling US dollars would also probably involve selling US bonds, causing yields to rise. Hence the idea of converting long-term bonds into century bonds at lower rates. Will that immediately add a credit risk premium into existing US T-bonds and notes? Who knows!

Plaza Accord

There is precedent for a multi-lateral agreement to bring down the dollar. In September 1986 when the dollar was at its all-time peak on the chart, the US Treasury engineered the ‘Plaza Accord’ – in which Japan, West Germany, France, and the UK agreed to sell dollars to bring down the dollar which had been soaring since Volcker’s inflation-busting 1980-2 recessions.

The Plaza Accord was highly effective – the dollar was driven down by co-ordinated selling pressure, starting almost immediately. It was so successful in driving down the dollar, that the US had to engineer the ‘Louvre agreement’ in February 1987 to try to halt further declines.

1987 crash

We can see on the chart that the Louvre Accord was not so successful. Instead of halting the decline, the dollar kept falling during 1987. On the last weekend in October, US Treasury Secretary James Baker made some off-the-cuff comments in a TV interview that he would not step in to support the dollar – indeed he threatened further devaluation to narrow the trade deficit. Those comments triggered the October 1987 stock market crash the next day.

This is precisely what is going on today – Trump and co are trying to talk down the dollar to narrow the trade deficit. The difference is how it is done. Details and execution are everything.

The Plaza and Louvre Accords were carefully negotiated formal agreements, and they did not rattle stock markets. In fact stock markets kept on booming while the co-ordinated currency action was being implemented. In contrast, Baker’s comments in October 1987 were unplanned, off-the-cuff, and they triggered immediate stock market crashes in the US and around the world.

Unfortunately, this time around, Trump’s modus operandi is probably more like the latter, not the former. Trump’s style is not conducive to co-ordinated multi-lateral agreements, carefully crafted communications, and calm markets!

Future of the US dollar?

For the past 54 years since Nixon officially ended the US dollar-gold peg, the world has been searching for an alternate to the US dollar, but we are no closer to a solution more than half a century later, despite countless proposals and experiments.

The US dollar is still used for the vast bulk of world trade and commodities pricing, and the US is still home to the largest, deepest, most liquid stock market, bond market, and currency market in the world. The US is still the engine of world growth – especially now with slowdown in China and stagnation in Europe – and the US dollar is still the chief fuel and lubricant for the engine.

Implications for Australian investors

The US dollar will be the global safe haven currency for some time yet, so the AUD will continue its usual pattern - rising (against the USD) in global booms, and then falling in global sell-offs when global investors (mostly US investors) pull their money back home to the US.

Therefore the usual currency strategy for international share holdings still applies: - hedged beats un-hedged when the AUD (almost always) rises in global booms; un-hedged beats hedged when the AUD always falls in global sell-offs. This has been the case since the float of the AUD in 1983, and will probably still apply while the USD remains the main global currency.

Conclusion

The end of the US dollar is not nigh!

The problem for the US is the reverse – it has been rising strongly at the expense of US producers and exporters. The challenge is to bring down the US dollar in a neat, orderly, well-planned, and well-flagged process that does not rattle markets.

Stay tuned.

‘Till next time. . . . safe investing!